Robo Boat: Robotics and environmental protection make the perfect pair for Volkan Isler

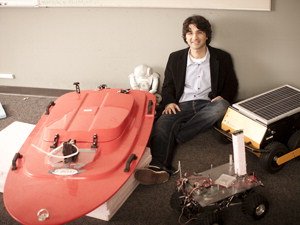

The first thing you see when you walk into Volkan Isler’s electronics-strewn laboratory is not the two-foot-tall humanoids crouched in a corner, or the Spiderman trick-or-treat bucket, or the Marvel comics posters on the wall—or even the roombas with video cameras soldered to their backs. It’s the boat.

No ordinary water craft

Red as a fire truck and shiny as a sports car, the 6-foot-long Oceanscience Q-Boat perches on Stryrofoam blocks in a shipping crate in the corner of the windowless room—being handled, as the lettering on the side of the crate admonishes, With Care. Except for what looks like a coat-hanger antenna sprouting midship and its intriguing Turkish name—Lavant—it seems an ordinary craft. But it’s much more than that: It’s the embodiment of Isler’s quest to bring advanced robotics to bear on the challenge of building a healthier planet.

“The project touches fundamental robotics problems I’ve been working on for 10 years, and it allows us to do something useful for society, so I’m very excited about it.”

Isler is a computer scientist, a College of Science and Engineering professor, a McKnight Land-Grant professor, an Institute on the Environment resident fellow, and an unabashedly big fan of high-functioning inanimate objects. His research goal is to develop robotic systems that can operate on their own in large, complex and dynamic settings. He’s particularly interested in doing so in areas that could provide some benefit in the realm of environmental monitoring.

“There’s lots of robotics stuff we want to do, both theory and applications,” he says. “When it solves environmental problems, it’s double-good.”

New tool for tracking carp

Before coming to the University of Minnesota in 2008, Isler had been working on mostly theoretical robotics problems, and was particularly well known for his work in advancing robots’ proficiency in winning pursuit-evasion games (think tag, only with no humans allows). Such research is not only challenging—it involves programming robots to respond rapidly and efficiently to unpredictable changes in the evader’s motion in such a way that guarantees eventual “capture”—but also of great practical value, with real-world uses ranging from collision avoidance to search and rescue. In the Land of 10,000 Lakes, Isler found the perfect evader for advancing his pursuit-evasion work: carp.

Turns out a College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resources faculty member, fisheries professor Peter Sorensen, was exploring ways to control these nonnative invasive fish that involved studying their movements within a lake. To that end, Sorensen had been capturing wild carp, implanting radio-tracking devices under their skin, then enlisting college students to chase them using motorboats and handheld monitoring devices.

“I thought that the robots could track the fish more accurately and for longer periods of time without the need for intensive human efforts,” Isler says. “However, this requires solving a number of fundamental robotics problems, such as multi-robot search and tracking, which makes the project very appealing for us.”

Isler took funds from his IonE fellowship to Home Depot for wood, PVC pipes and big plastic tubs. He and his talented team of students added sensors and computers to the mix and crafted a robotic raft. Then they began working on programming the raft to find and track a moving object. After achieving success with the do-it-yourself project, Isler put in an order to Lavant, since he felt they needed a more robust platform for the hull.

From concept to reality

Since the red robotic rover arrived on the scene in the spring of 2010, Isler has been working with his students to construct, test and refine the complex mathematical algorithms it needs to successfully navigate the complex and constantly changing environment defined by wind, current, battery power, and elusive and unpredictable fish. With a series of successful field trials serving as proof of concepts, he recently put together a team of robotic experts, computer scientists, computer engineers, mathematicians and fish biologists and successfully applied for a $2.2 million National Science Foundation grant to build a network of carp-chasing robotic boats that eventually may be available for use by fisheries managers around the country.

“The project touches fundamental robotics problems I've been working on for 10 years,” Isler says. “And it allows us to do something useful for society, so I'm very excited about it.”

As enthusiastic as he is about Lavant’s success so far, Isler notes there’s plenty left to perfect. He and his students are now working to build energy-efficient search and tracking algorithms for multiple robots so they can operate in large and complex lakes in a robust fashion. They’re also planning to incorporate solar panels and energy harvesting into their algorithms so the robots can remain on the field for long periods.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg, robot-meets-environment-wise. In the big picture, Isler has his eyes on applying his robotics expertise to developing a global-scale environmental sensing system he calls “Googling the Planet.” Based on an international network of robots, the system would make it possible for researchers to remotely gather real-time data about local conditions on command from anywhere in the world.

“Googling the Planet will enable scientists to query nature just like they query the Internet,” he says. “That’s the grand plan.”