Volcanoes of the deep: Researcher studies earth forms beneath the ocean

Far from my University of Minnesota home, I was part of a multiuniversity mission to learn more about how Earth's surface is formed--and most of it forms under the waves.

As we slowly descended, the three of us went over our dive plan, enjoyed the bioluminescent plankton, checked out what was for lunch (peanut butter and jelly), and negotiated leg space.

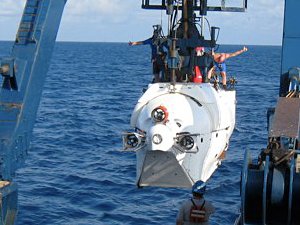

The latter is often required inside the confines of the six-foot-wide titanium sphere that makes up the human working space of the Alvin submersible, which carries two science observers and a pilot to ocean depths of up to 2.5 miles. Today we would reach about 9,185 feet.

Although this was my second time in Alvin, it was my first diving on a mid-ocean ridge. This ridge (the Galapagos Spreading Center, or GSC) is essentially a long chain of underwater volcanoes where new ocean crust is generated. Our job as scientists was to plan the dive track, look, take careful notes, and select which rocks to sample.

Seventy percent of Earth's crust is generated at mid-ocean ridges like the GSC, yet compared to our knowledge of how volcanoes work on land, we know little about them. How often do eruptions occur? How big are they? What processes deeper in the Earth control how magma is generated and delivered to the surface? Why do some sections of the GSC have lots of seamounts (underwater mountains) while others do not? These questions go to the heart of how our Earth works.

To better answer them, we need detailed maps of different lava flows and data on when the flows erupted, as well as something about the chemistry of the rocks. Mapping surface features is easy on land, but try it on a moonless night with only a flashlight. Now add several thousand feet of water. No wonder we know more about what the surface of Mars looks like than we do the bottom of the ocean.

But today, being the first people to visit this particular place on Earth was enough. By the end of our seven-hour dive, we had seen beautiful "pillow-lavas" that form when lava slowly squeezes out through a small opening like toothpaste from a tube. These types of lavas tend to form rough, bumpy seafloor.

Other lava flows were much smoother, and occasionally we saw the remains of channels through which this lava flowed, or the remnants of a lava lake that had drained away. Of course, we also saw colorful sea stars, exotic-looking fish, anemones, squid, and crinoids (an animal that looks like a flower from Dr. Seuss).

It may be many years before I make it back to the bottom of the ocean), but the samples and data we collected will keep us busy and keep the good memories alive.

-- Bowles' journey to the Galapagos Spreading Center was part of a seven-university scientific mission led by the University of Hawaii and the University of South Carolina. Check out more photos and fun facts about the expedition. The Alvin is owned by the U.S. Navy and operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.