Destructive alga uses toxins to become a vicious predator rather than helpless prey, university researchers say

Contacts: Ryan Mathre, University News Service, mathre@umn.edu, (612) 625-0552

Rhonda Zurn, Institute of Technology, rzurn@umn.edu, (612) 626-7959

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (01/11/2010) A team of researchers, including University of Minnesota aerospace engineering and mechanics faculty member Jian Sheng, have uncovered new information about a toxic alga that shows it to be a vicious, venom-producing predator rather than merely a helpless sun-loving microbe. The alga has been blamed for harmful algal blooms known as mahogany tides that have resulted in massive fish kills in Chesapeake Bay and other waterways worldwide.

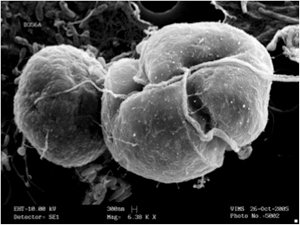

The researchers studied K. veneficum, a toxic algal cell, known as a dinoflagellate, found in estuaries worldwide. Each year millions of dollars are spent on measures to control dinoflagellates around the globe. This species is known to release a substance called karlotoxin, which is extremely damaging to the gills of fish.

An ecological role for producing karlotoxin was previously understood to be a form of self-defense against natural predators to relieve grazing pressure. However, in a series of experiments using 3-D digital holographic microscopy initially developed at The Johns Hopkins University, Sheng and his colleagues have found that the release of these toxins also serve to stun prey before ingestion. This shifts the role from one of protection to one of aggression.

The research paper entitled A dinoflagellate exploits toxins to immobilize prey prior to ingestion was published today in the current issue of the prestigious scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Researchers in addition to Sheng who are part of the team include Joseph Katz, a professor of mechanical engineering in the Whiting School of Engineering at The Johns Hopkins University; Edwin Malkiel, an adjunct associate research scientist in Johns Hopkins Department of Mechanical Engineering; Jason E. Adolf, an assistant professor in the University of Hawaii's Department of Marine Science; and Allen R. Place, a professor in the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute's Center of Marine Biotechnology in whose laboratory karlotoxin was discovered and characterized.

In the paper, we have answered why these complicated molecules are made in nature in the first place and identify a possible alternative mechanism causing massive bloom, said Sheng, a University of Minnesota fluid mechanics expert who began this collaboration with the Place laboratory while earning his doctorate in Katz's lab at Johns Hopkins. We further suggest a new venue of predicting and eventually mediating the bloom events.

Using 3-D high-speed holographic microscopy, the researchers studied the relationship between K. veneficum and its prey, a common, single-celled algal cell called a cryptophyte. They found that K. veneficum releases toxins (karlotoxins) to slow down prey prior to ingestion assumedly so as to increase predation success rate and promote its own growth. This significantly shifts the understanding about what permits blooms to initiate and form. Instead of mortality prevention, the organism's actions relate more closely to growth promotion through ingestion of a pre-package food source, the cryptophyte cell.

The University of Minnesota Department of Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics is one of 12 academic departments and 18 research centers that make up the Institute of Technology, the university's college of science and engineering.