Minnesota Astrophysicists Help Spot Rare Stellar Collision

Researchers, including astrophysicists from the University of Minnesota, have identified a white dwarf/brown dwarf collision in the star CK Vulpeculae. Professors Charles Woodward and Robert Gehrz are part of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) collaboration that discovered the object, long thought to be a nova, is actually a remnant of a rare type of solar collision.

The star was first observed in 1670, appearing as a new star in the constellation in the constellation Cygni. It brightened then disappeared two years later. Twentieth-century astronomers thought that it was a star that occasionally blows off mass, though it never quite fit the pattern typical of these nova events. Using the ALMA array, astrophysicists have been able to see that the event was actually a collision between a white dwarf (a star similar to our sun in the later stages of its life) and a brown dwarf (a star without enough mass to sustain nuclear fusion.)

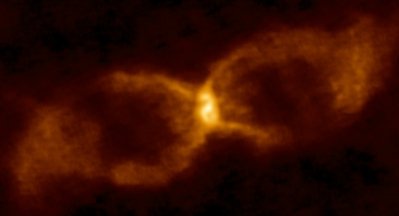

It is not unusual for a white dwarf and brown dwarf to orbit one another, but it is unusual for them to collide. "It was as if you put salsa fixings into a blender and forgot to put the lid on,” Woodward said. “The white dwarf was like the blades at the bottom and the brown dwarf was the edibles. It was shredded, and its remains spun out in two jets—like a jet of goop shooting from the top of your blender as you searched frantically for the lid.”

The debris formed a distinctive hour-glass shape. The ALMA group studied the light from two background stars that had passed through the system, the researchers noted the presence of lithium, a light element that can’t exist in the interiors of stars, where nuclear fusion occurs. They also found organic molecules like formaldehyde and methyl alcohol, which also would perish in stellar interiors. They reasoned that these molecules must have been produced in the debris from the collision.

The amount of dust in the debris was about one percent the mass of the sun.

“That’s too high for a classical nova outburst and too low for mergers of more massive stars, as had been proposed earlier,” said Sumner Starrfield, a professor at Arizona State University who was involved in the study.

That evidence, plus isotope data, led to the conclusion that the collision was between a white dwarf and brown dwarf. And the remnant star is still blowing off material.

“Collisions like this could contribute to the chemical evolution of our galaxy and universe,” noted Minnesota’s Gehrz. “The ejected material travels out into space, where it gets incorporated into new generations of stars.”