Dry spells spelled trouble in old China

In ancient China, drought may have helped topple dynasties

By Deane Morrison

History does not record whether Chongzhen, the last of China's Ming emperors, appreciated his country's summer rains. Let's hope he did while they lasted, because new evidence suggests a letup in those rains could have fueled the popular uprising that toppled Chongzhen and his 276-year-old dynasty in A.D. 1644.

China has seen many dynasties rise and fall, but a study led by U researchers and their colleagues at China's Lanzhou University has identified a weakening of the summer Asian Monsoons as a possible last straw for some of them. Such weakening, and the attendant loss of precipitation, accompanied the fall of three dynasties and now could be reducing rainfall in northern China again.

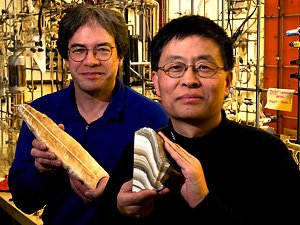

The work rests on climate records preserved in the layers of stone in a 4.6-inch stalagmite found in Wanxiang Cave in Gansu Province, China. The stalagmite built up over 1810 years; stone at its base dates from A.D. 190, and stone at its tip was laid down in A.D. 2003, the year the stalagmite was collected.

"It is not intuitive that a record of surface weather would be preserved in underground cave deposits. This research nicely illustrates the promise of paleoclimate science to look beyond the obvious and see new possibilities," says David Verardo, director of the U.S. National Science Foundation's Paleoclimatology Program, which funded the research.

By measuring amounts of the elements uranium and thorium throughout the stalagmite, the researchers could tell the date each layer was formed. And by analyzing the "signatures" of two forms of oxygen in the stalagmite, they could match amounts of rainfall a measure of summer monsoon strength to those dates.

"Summer monsoon winds originate in the Indian Ocean and sweep into China," explains study leader Hai Cheng, a research scientist at the University of Minnesota. "When the summer monsoon is stronger, it pushes farther northwest into China."

These moisture-laden winds bring rain necessary for cultivating rice. But when the monsoon is weak, the rains stall farther south and east, depriving northern and western parts of China of summer rains. A lack of rainfall could have contributed to social upheaval and the fall of dynasties.

The researchers discovered that periods of weak summer monsoons coincided with the last years of the Tang (A.D. 618-907), Yuan (A.D. 1271-1368), and Ming (A.D. 1368-1644) dynasties, which are known to have been times of popular unrest. Conversely, the research group found that a strong summer monsoon prevailed during one of China's "golden ages," the Northern Song Dynasty (A.D. 960-1127). The ample summer monsoon rains may have contributed to the rapid expansion of rice cultivation from southern China to the midsection of the country. During the Northern Song Dynasty, rice first became China's main staple crop, and China's population doubled.

"The waxing and waning of summer monsoon rains are just one piece of the puzzle of changing climate and culture around the world," says Larry Edwards, a professor of geology and geophysics and a 2009 Guggenheim Fellow. For example, the study showed that the dry period at the end of the Tang Dynasty coincided with a previously identified drought in Meso-America that has been linked to the fall of the Mayan civilization.

The study also showed that the plentiful summer rains of the Northern Song Dynasty coincided with the beginning of the well-known Medieval Warm Period in Europe and Greenland. During this time the late 10th century Vikings colonized southern Greenland. Centuries later, a series of weak monsoons prevailed as Europe and Greenland shivered through what geologists call the Little Ice Age. In the 14th and early 15th centuries, as the cold of the Little Ice Age settled into Greenland, the Vikings disappeared from there. At the same time, on the other side of the world, the weak monsoons of the 14th century coincided with the end of the Yuan Dynasty.

A second major finding concerns the relationship between temperature and the strength of the monsoons. For most of the last 1810 years, as average temperatures rose, so, too, did the strength of the summer monsoon. That relationship flipped, however, around 1960, a sign that the late 20th century weakening of the monsoon and drying in northwestern China was caused by human activity.

If carbon dioxide is the culprit, as some have proposed, the drying trend may well continue in Inner Mongolia, northern China, and neighboring areas on the fringes of the monsoon's reach, as society is likely to continue adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere for the foreseeable future. If, however, the culprit is man-made soot, as others have proposed, the trend could be reversed, the researchers said, by reduction of soot emissions.

Lawrence Edwards is the George and Orpha Gibson Chair of Earth Systems Sciences and a Distinguished McKnight University Professor.