Contributions to change

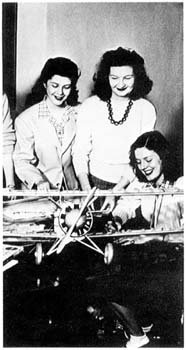

Photo courtesy of the UMN Digital Archives.

At four other historic times, CSE alumni and faculty met the challenges

December 21, 2020

Jumping in to lend expertise is embedded in the DNA of our college—and in the minds and hearts of those who teach here, research here, study and graduate from here.

As we approach the 12-month mark since COVID-19 led to stay-at-home orders and a new way of life for most of us, we can rest knowing there are those in our community of scientists, engineers, and mathematicians who continue to keep their eyes focused on this deadly virus.

Their acts of trying to understand. the virus, model it, tame it, and help in numerous other ways—such as developing personal protective equipment—reflect past behavior.

For more than a century, University of Minnesota scientists and engineers have pioneered research, innovation, and technology.

Here is a sample of four other important crossroads in history when our University community worked to meet the challenges of our nation.

World War II

As many young men were drafted during World War II, women in CSE—then known as the Institute of Technology—stepped up. In 1943, more than 100 female students were trained to work as aeronautical engineers for the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. Dubbed the Curtiss-Wright Cadettes, the women provided a creative solution to the industry’s dwindling supply of engineers at the time.

CSE researchers and alumni were also hard at work on technological innovations that would revolutionize the war.

Chemistry professor Izaak Kolthoff developed a technique for making synthetic rubber for the military industry. Alumnus Walter Spievak (Aero ’36) helped design the B-25 bomber plane at Boeing, and alumnus Edgar Piret (ChE ’32) invented a dehydrated meat product for troops to pack as combat rations during the war. Physics professor Alfred O.C.

Nier pioneered research on fissionable uranium isotopes that would eventually assist Manhattan Project scientists in creating the atomic bomb.

America’s race to the moon

Global competition spiked during the Cold War era, leading to the inevitable “space race” in the 1960s.

Jeannette Piccard and her husband, University of Minnesota aeronautical engineering professor Jean Piccard, laid the groundwork for piloted space flights decades earlier when they set a record altitude of 57,979 feet in a high-altitude balloon in 1934.

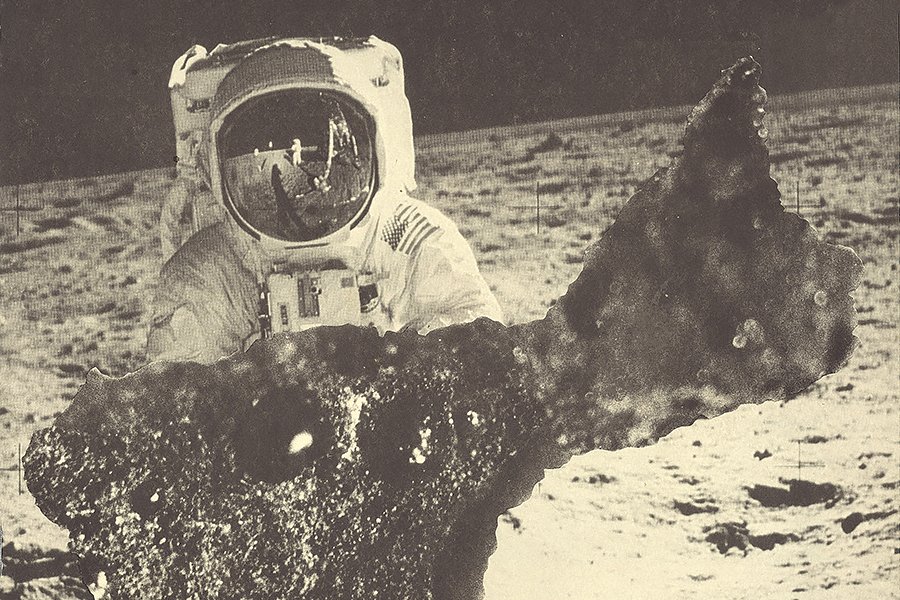

CSE’s involvement in the space race continued when professor Helmut Heinrich developed supersonic parachutes that contributed to the Apollo moon landings. In 1969, earth science professor V. Rama Murthy and physics professor Robert Pepin became the first scientists to study rocks from the Apollo 11 moon landing. Alumnus

Donald K. “Deke” Slayton (Aero ‘49) later commanded the Apollo-Soyuz space mission in 1975.

Digital revolution

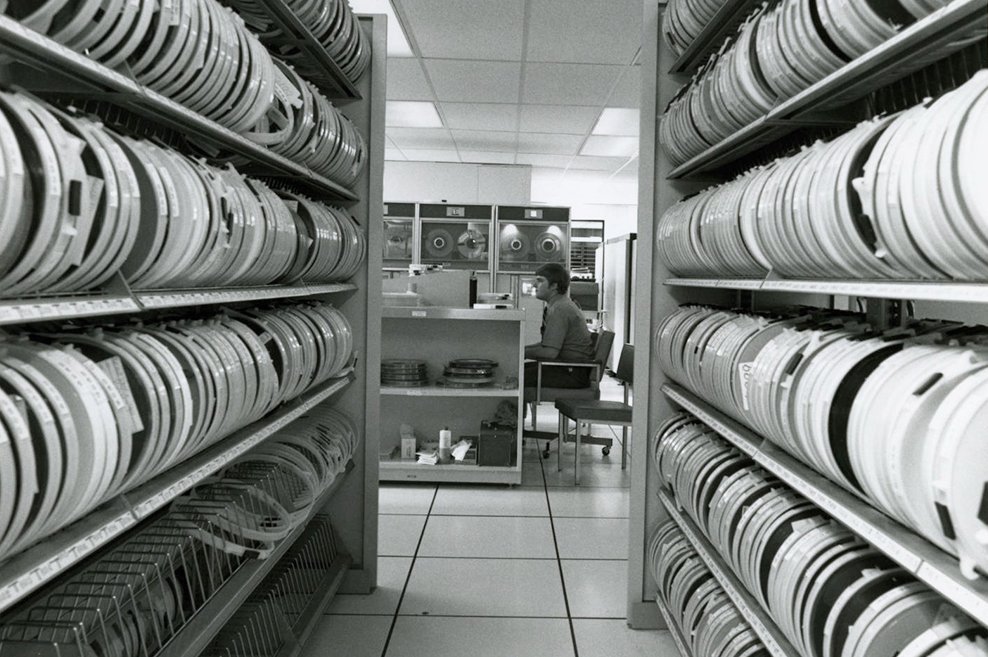

In 1972, Seymour Cray (EE ’49) founded Cray Research and led the development of supercomputers. Former faculty member John Bardeen won his second Nobel prize in physics that year, for developing the theory of superconductivity.

In the late 1980s, Mark McCahill (Chem ’79) led the University of Minnesota team that developed POPmail, one of the first popular Internet e-mail clients. He also steered the Gopher protocol development team, which included another CSE alumnus, Paul Lindner (CompSci ’91).

“In its heyday, Gopher demonstrated the potential of the Internet as an information system for the [average person], beyond its status as a tool (or toy) for tech enthusiasts, academics, and high-level researchers,” according to an article by The Chronicle of Higher Education.

The Gopher, an information organization and transmission system—often regarded as a precursor to today’s Internet—was initially released in 1991.

“Spanish flu”

By 1918, the year of the devastating influenza pandemic, eight CSE departments had been established: civil engineering (1910), biosystems and agricultural engineering (1909; later renamed bioproducts and biosystems engineering), mechanical engineering (1898), mathematics (1894), chemistry (1893), astronomy (1892), electrical engineering (1891), and physics (1889).

The University became a military training camp for more than 3,200 soldiers and the University Health Service, now Boynton Health, saw 100 patients each day.

One-third of the world’s population, or about 500 million people, became infected. Control efforts globally were limited to isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and restrictions on public gatherings. For more on the University’s response then, which mirrors COVID-19 efforts today, see z.umn.edu/mndaily1918flu.

Read more stories from our Winter 2021 college magazine.

Story by Olivia Hultgren and Pauline Oo

If you’d like to support research in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, visit our CSE Giving website.