CSE research leads to startup company that aims to improve water quality

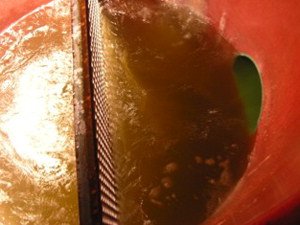

Contacts: John Merritt, Office of the VP for Research, merri205@umn.edu, (612) 624-2801 Patty Mattern, University News Service, mattern@umn.edu, (612) 624-2801 The device was developed at the Saint Anthony Falls Laboratory (SAFL), a research unit within the University's College of Science and Engineering. Researchers nicknamed the device the "SAFL Baffle" and are finding it to be a cost-effective method for preventing harmful sediments carried by storm water from reaching Minnesota lakes and streams. As water makes its way into storm sewers after a rainstorm, and eventually into lakes and rivers, it picks up sediments like sand and gravel along the way. These sediments sometimes contain nutrients that can interrupt the biological balance of lakes and streams and can be harmful to plant life. "Urban runoff hits the road, goes into the storm sewers and ends up in receiving water bodies like lakes and rivers," said John Gulliver, a civil engineering professor in the U of M's College of Science and Engineering and co-inventor of the SAFL Baffle. "Cities are required to treat urban runoff and are trying to figure out how to deal with this." The SAFL Baffle is installed in a sump -- a vertical cylinder that connects two or more sewer pipes. There are usually 30 to 40 sumps in the sewer system on a given street. The Baffle slows down water rushing into the sump and prevents it from picking up sediments that have settled there during low-flow periods. "Existing sumps are catching sediments for small storms, but if a big storm comes along, it will wash all those sediments back out," Gulliver said. "So we devised a simple technique to keep the sediments in the sump during high flow events. Its main purpose is to prevent the sediment from being scoured out when you have high flow." The SAFL Baffle can be installed in existing sumps as well as new structures. It would be more cost-effective than existing devices currently on the market. Existing devices, which cost about 10 times more than the SAFL Baffle, also remove floating trash, oil, grease, and heavy metals. These additional features are often unnecessary, because a separate device can be installed at the street level to remove trash. A combination of this device and the SAFL Baffle will do the same job as devices currently on the market, at a fraction of the price. "The current devices that are on the market have a lot of features that are generally not needed," said A.J. Schwidder, CEO of Upstream Technologies and a Carlson School of Management MBA student. "Those devices are a lot more expensive than the SAFL Baffle, which just does sediment removal. So the customer is only paying for what they need." The SAFL Baffle is due to be installed in sumps in Minneapolis, Prior Lake and Bloomington in February. "One of the attractive things about the SAFL Baffle is that there are real customers who want to purchase it now," said Dale Nugent, marketing manager for the U of M's Office for Technology Commercialization. "It's affordable and meets a pressing need for sediment control. We are grateful that the Minnesota Department of Transportation sponsored research with the Saint Anthony Falls Laboratory to help translate this need into a market-ready solution." Gulliver and his research team are happy to have solved an environmental threat with such a simple device. "We were surprised that this simple solution worked so well and nobody else had tried it," he said. The research of Gulliver's team was funded by the Minnesota Local Road Research Board. The organization funds research to improve transportation in the state and is affiliated with the Minnesota Department of Transportation. The device was invented by Gulliver, civil engineering adjunct professor Omid Mohseni, and graduate student Adam Howard.