Gravitational waves detected from second pair of colliding black holes

U of M researchers comment on findings

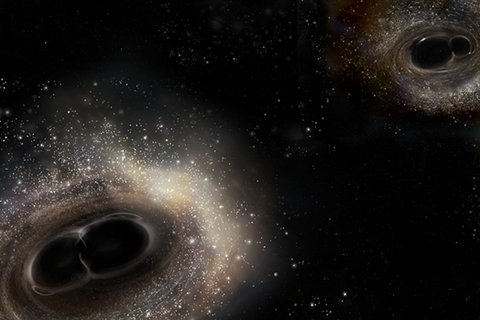

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (6/15/16) — The two LIGO gravitational wave detectors in Hanford Washington and Livingston Louisiana have caught a second robust signal from two black holes in their final orbits and then their coalescence into a single black hole. This event, dubbed GW151226, was seen on December 26th at 03:38:53 (in Universal Coordinated Time, also known as Greenwich Mean Time), near the end of LIGO's first observing period ("O1"), and was immediately nicknamed "the Boxing Day event."

Like LIGO's first detection earlier this year, this event was identified within minutes of the gravitational wave's passing. Subsequent careful studies of the instruments and environments around the observatories showed that the signal seen in the two detectors was truly from distant black holes – some 1.4 billion light years away, coincidentally at about the same distance as the first signal ever detected.

Gravitational waves carry information about their origins and about the nature of gravity that cannot otherwise be obtained, and physicists have concluded that these gravitational waves were produced during the final moments of the merger of two black holes—14 and 8 times the mass of the sun—to produce a single, more massive spinning black hole that is 21 times the mass of the sun.

“This discovery complements what we learned from the first detection,” says Vuk Mandic, University of Minnesota School of Physics and Astronomy associate professor and leader of the Minnesota’s LIGO group. “For example, the mass of this system is significantly smaller than that of the first observed binary black hole merger, so we are beginning to learn about the range of possible masses of such systems, which in turn may tell us something about their origins.”

During the merger, which occurred approximately 1.4 billion years ago, a quantity of energy roughly equivalent to the mass of the sun was converted into gravitational waves. The detected signal comes from the last 27 orbits of the black holes before their merger. Based on the arrival time of the signals—with the Livingston detector measuring the waves 1.1 milliseconds before the Hanford detector—the position of the source in the sky can be roughly determined.

The first detection of gravitational waves, announced on February 11, 2016, was a milestone in physics and astronomy; it confirmed a major prediction of Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity, and marked the beginning of the new field of gravitational-wave astronomy.

“The discovery of two binary black hole mergers in the first observation run of Advanced LIGO detectors is a great indication of what is to come,” said Dr. Gwynne Crowder, a postdoctoral researcher in Mandic’s group. “We are expecting additional runs in the coming years, with increasing sensitivity and with additional detectors. We are just beginning to explore the potential of gravitational-wave observations.”

Advanced LIGO’s next data-taking run will begin this fall. By then, further improvements in detector sensitivity are expected to allow LIGO to reach as much as 1.5 to 2 times more of the volume of the universe. The Virgo detector is expected to join in the latter half of the upcoming observing run.

The LIGO Observatories are funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), and were conceived, built, and are operated by Caltech and MIT. The discovery, accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters, was made by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (which includes the GEO Collaboration and the Australian Consortium for Interferometric Gravitational Astronomy) and the Virgo Collaboration using data from the two LIGO detectors.

LIGO research is carried out by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC), a group of more than 1,000 scientists from universities around the United States and in 14 other countries. More than 90 universities and research institutes in the LSC develop detector technology and analyze data; approximately 250 students are strong contributing members of the collaboration. The LSC detector network includes the LIGO interferometers and the GEO600 detector.

Virgo research is carried out by the Virgo Collaboration, consisting of more than 250 physicists and engineers belonging to 19 different European research groups: 6 from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France; 8 from the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) in Italy; 2 in The Netherlands with Nikhef; the Wigner RCP in Hungary; the POLGRAW group in Poland and the European Gravitational Observatory (EGO), the laboratory hosting the Virgo detector near Pisa in Italy.

The NSF leads in financial support for Advanced LIGO. Funding organizations in Germany (Max Planck Society), the U.K. (Science and Technology Facilities Council, STFC) and Australia (Australian Research Council) also have made significant commitments to the project.

Several of the key technologies that made Advanced LIGO so much more sensitive have been developed and tested by the German UK GEO collaboration. Significant computer resources have been contributed by the AEI Hannover Atlas Cluster, the LIGO Laboratory, Syracuse University, the ARCCA cluster at Cardiff University, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and the Open Science Grid. Several universities designed, built, and tested key components and techniques for Advanced LIGO: The Australian National University, the University of Adelaide, the University of Western Australia, the University of Florida, Stanford University, Columbia University in the City of New York, and Louisiana State University. The GEO team includes scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute, AEI), Leibniz Universität Hannover, along with partners at the University of Glasgow, Cardiff University, the University of Birmingham, other universities in the United Kingdom and Germany, and the University of the Balearic Islands in Spain.