Researchers produce detailed image of gigantic galaxy-cluster collision

Image captures region 800 million light years away

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (03/12/2015) — A University of Minnesota astrophysicist is part of a national team of researchers that has produced the most detailed image yet of a fascinating region where clusters of hundreds of galaxies are colliding, creating a rich variety of mysterious phenomena visible only to radio telescopes.

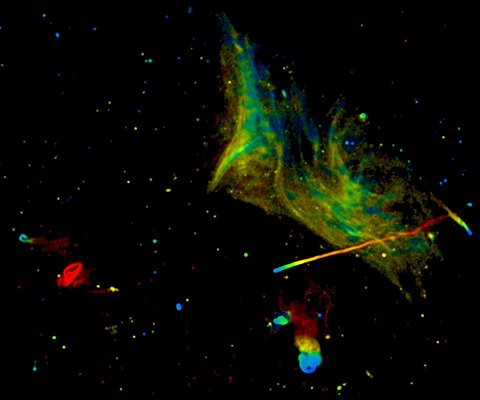

The scientists took advantage of new capabilities of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) to make a "true color" radio image. This image shows the region as it would appear if human eyes were sensitive to radio waves instead of light waves. In this image, red shows where longer radio waves predominate, and blue shows where shorter radio waves predominate, following the pattern we see in visible light.

The image shows a number of strange features the astronomers think are related to an ongoing collision of galaxy clusters. The region is called Abell 2256, and is about 800 million light years from Earth and some 4 million light years across. The image covers an area in the sky almost as large as the full moon. Studied by astronomers for more than half a century with telescopes ranging from radio to X-ray, Abell 2256 contains a fascinating variety of objects, many of whose exact origins remain unclear.

With monikers such as "Large Relic," "Halo," and "Long Tail," the features in this region are seen in greater fidelity than ever before, said lead researcher Frazer Owen from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO).

"The image reveals details of the interactions between the two merging clusters and suggests that previously unexpected physical processes are at work in such encounters," Owen said.

Owen worked with Lawrence Rudnick from the University of Minnesota; Jean Eilek of New Mexico Tech; and Urvashi Rau, Sanjay Bhatnagar, and Leonid Kogan of NRAO.

"The radio emissions we see in the image come from very high energy electrons, moving at nearly the speed of light,” Rudnick said. “We use the colors to help figure out how these electrons gain and lose energy as the clusters of galaxies collide."

The researchers recently presented their results in the Astrophysical Journal.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.