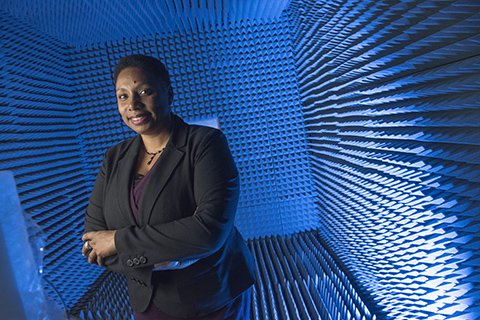

Rhonda Franklin: Reaching out

Written by Kermit Pattison

March 6, 2017

Rhonda Franklin is living proof that outreach efforts have a real effect.

Franklin, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, is a microwave and radio frequency engineer. She seeks to innovate new ways to “make novel communication circuits today that we could only talk about in theory yesterday.” She hopes to accomplish something similar in academic culture: to widen pathways that were narrow and difficult to navigate yesterday.

Franklin grew up in Houston, Texas as the child of two teachers, both first-generation college graduates. Her mom was a remedial math teacher and her father an industrial arts teacher turned businessman. In high school, she excelled in math and science so her teachers and counselors encouraged her to consider majoring in engineering. Her senior counselor had other ideas. “My senior counselor thought I should become a secretary,” she said. “I was number two in my class and wanted to explore a wider range of options.

Franklin didn’t know any engineers and entertained vague plans to become a lawyer. With the encouragement of her STEM teachers, she attended an engineering summer camp sponsored by the National Science Foundation. “That was my first exposure to engineering and the different versions,” she recalls. “By the end of the week, I said ‘I really like this.’”

At Texas A&M University, she majored in electrical engineering. The department had only one female faculty member. Often Franklin was the only female and minority student in her classes. She encountered many reminders, subtle and overt, that her chosen field and the academic environment that prepared the workforce were not prepared to teach students who were different from the norm. There were bittersweet moments and it was hard to get used to people having low or no expectations. “In my African American community, people expected a lot of me and I expected a lot of myself.” Despite these unpleasant moments, it was the help and support of a select few progressive peers, staff, and professors who were key advocates for her education that kept her going. She calls them her “Earth angels.” Today we call them “mentors.”

“Thankfully, engineers are introverts,” she said. “I don’t need a whole lot of people to keep me going. I’ve been fortunate along the way to meet just the right person when needed among family, friends, and my academic community."

In graduate school at the University of Michigan, she was the first African-American woman in her microwave engineering program. The year she graduated, only six African-Americans (male and female) earned engineering Ph.D.s in the entire U.S.

Another outreach program helped open doors. She won a master’s and eventually doctoral fellowship to attend graduate school sponsored by The National GEM Consortium, a network of universities, government laboratories, research institutions and corporations. The fellowship supported students from underrepresented communities to pursue graduate education in applied science and engineering. Franklin spent three summers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, her sponsor, which gave her research experience, professional mentors who helped her identify her research interest, and the confidence to blaze a path in academia.

In 1998, she joined the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering faculty at the University of Minnesota. That year she received the prestigious Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineering from President Bill Clinton for her research area on packaging and integration methods to combine microwave electronic circuits with optical ones in communication systems. Franklin was not only the first woman to earn tenure in her department as an assistant professor, but is also the first African-American woman to do so in both her department and the entire college.

She has made a commitment to ensure the path will not be so unusual to those who follow. Franklin, the mother of a high school student, speaks at schools and encourages students to imagine themselves in a profession where they can make a difference despite the lack role models among friends or family that look like them. She keenly remembers the difference that a few key supporters made in her own life, especially her advisor and research group.

“It takes 22 years to grow an engineer,” she said. “This is an expensive resource. We should support it and help it thrive. I hope in my career I can strive with my team of diverse students to help advance my field technically, but I also hope and am equally committed to helping make our academic and engineering community a place where all can create, innovate, and feel like they belong to a community that values their presence and contribution. I am confident that with the help of my colleagues, we can help create an environment where all of our students can thrive and not just survive.”