U of M astronomers part of team that has discovered solid buckyballs in space

Contacts:

Rhonda Zurn, College of Science and Engineering, rzurn@umn.edu, (612) 626-7959

Kristin Anderson, University News Service, kma@umn.edu, (612) 624-1690

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (02/22/2012 ) - University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering astronomers Robert Gehrz and Charles Woodward are part of an international team that have, for the first time, discovered buckyballs in a solid form in space. The discovery of these carbon molecules in space may provide clues about the origins of the Universe and if life could exist on other planets.

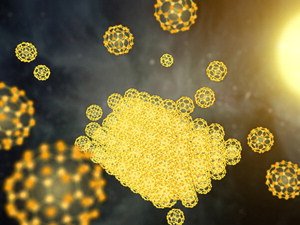

Formally named buckminsterfullerene, buckyballs are named after their resemblance to the late architect Buckminster Fuller's geodesic domes. They are made up of 60 carbon molecules arranged into a hollow sphere, like a soccer ball. Their unusual structure makes them ideal candidates for electrical and chemical applications on Earth, including superconducting materials, medicines, water purification and armor.

Prior to this discovery, the microscopic carbon spheres had been found only in gas form in the cosmos. In the latest discovery, scientists used data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope to detect tiny specks of matter, or particles, consisting of stacked buckyballs. They found the particles around a pair of stars called "XX Ophiuchi" or "XX Oph" that are 6,500 light-years from Earth, and detected enough to fill the equivalent in volume to 10,000 Mount Everests.

"These buckyballs are stacked together to form a solid, like oranges in a crate," said Nye Evans of Keele University in England, lead author of a paper appearing in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. "The particles we detected are miniscule, far smaller than the width of a hair, but each one would contain stacks of millions of buckyballs."

Buckyballs were detected definitively in space for the first time by Spitzer in 2010. Spitzer later identified the molecules in a host of different cosmic environments. It even found them in staggering quantities, the equivalent in mass to 15 Earth moons, in a nearby galaxy called the Small Magellanic Cloud.

In all of those cases, the molecules were in the form of gas. The recent discovery of buckyballs particles means that large quantities of these molecules must be present in some stellar environments in order to link up and form solid particles. The research team was able to identify the solid form of buckyballs in the Spitzer data because they emit light in a unique way that differs from the gaseous form.

University of Minnesota astronomers Gehrz and Woodward were involved in designing the program of infrared spectroscopic observations using Spitzer to determine the mineral content of the grains being produced in the XX Oph system. Such information helps scientists determine the essential building blocks of our Universe. Gehrz and Woodward also were involved in analyzing and interpreting the data. Some of the information they uncovered was surprising

"Although gaseous C60 molecules had already been detected in space in low density vapor form, it was a big surprise to find that they actually had condensed into solid grains,” Gehrz said. “Our research suggests that buckyballs are even more common in space than we ever imagined."

"We are all still surprised by nature," Woodward said. "The presence of C60 and other organic molecules in space hold some interesting clues to whether life in the Universe may also be common."

Buckyballs have been found on Earth in various forms. They form as a gas from burning candles and exist as solids in certain types of rock, such as the mineral shungite found in Russia, and fulgurite, a glassy rock from Colorado that forms when lightning strikes the ground. In a test tube, the solids take on the form of dark, brown "goo."

"The window Spitzer provides into the infrared universe has revealed beautiful structure on a cosmic scale," said Bill Danchi, Spitzer program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "In yet another surprise discovery from the mission, we're lucky enough to see elegant structure at one of the smallest scales, teaching us about the internal architecture of existence."

To read the full paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, visit: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-3933.2012.01213.x/abstract