Wild rice and cultural collaboration

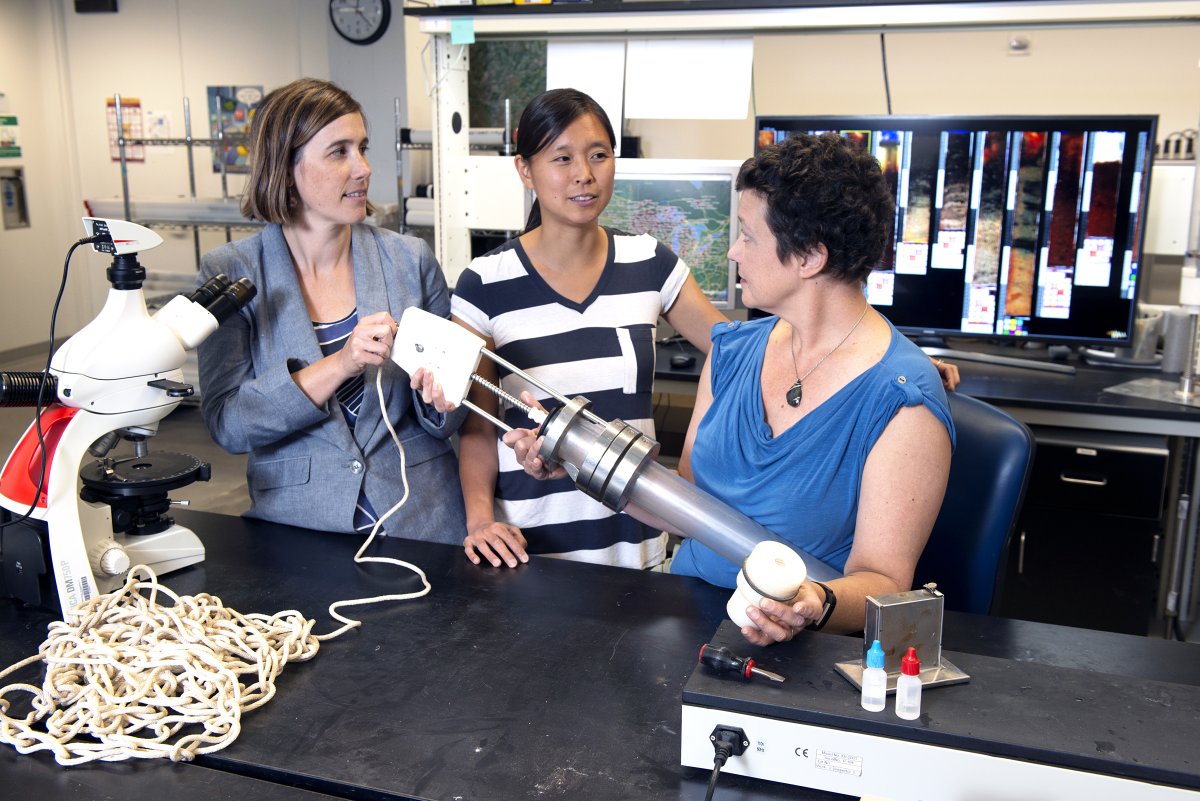

Above: The scientists with a core sampling tool in the LacCore-Continental Scientific Drilling Coordination Office (CSDCO) in Tate Hall.

CSE researchers looking to wild rice as an indicator of healthy water

November 9, 2018

Wild rice conservation in the Great Lakes region is a complicated business. That’s what three College of Science and Engineering researchers, working on a two-year University of Minnesota Grand Challenges Research Grant with Indian tribes, state and federal scientists, and social scientists, are quickly discovering.

First, wild rice depends on clean water. Even sulfate, an otherwise relatively benign pollutant, interacts with microbes in lake and stream sediments to form toxic sulfide, which severely limits wild rice growth.

“We know that microbes play a really important role in the availability of nutrients and type of pollutants that are in the water, but we’re just starting to understand how they may affect an entire ecosystem,” said Cara Santelli, a co-principal investigator and assistant professor of Earth sciences who recently earned a National Science Foundation CAREER award. “One of our goals is to think of wild rice habitats as an entire ecosystem.”

Wild rice yield is also limited by water murkiness and temperature, water-level fluctuations, plus winter length and cold. What remains unknown: the effect of metals such as mercury, competing plants, and invasive organisms such as zebra mussels.

“This project intrigued me because here was a problem that involved water, plants, contaminants, geochemistry,” said Earth sciences assistant professor Gene-Hua Crystal Ng.

“I saw this funding opportunity as a chance to assemble a team that could look at all these different factors,” adds Ng, the McKnight Land Grant Professor who’s leading the wild rice project.

Ng first thought their most important task was to untangle the many physical environmental factors that affect and potentially threaten wild rice production. But she soon discovered the issue was even more complicated than that.

Even though wild rice is finicky about its physical environment, it also exists in a social and political ecosystem. While it is of casual concern to many Minnesotans, the grass is of vital cultural and spiritual importance to Great Lakes Ojibwe tribes who for much of their history have been sidelined in environmental decisions. Tribes are seeing declines in wild rice production on their lands and other areas in northeastern Minnesota and Wisconsin where Indians and non-Indians gather it in late summer.

“Wild rice is extremely, profoundly important for Native American communities throughout the Great Lakes region,” Ng explained. “For the Ojibwe people, their migration story is linked to this food that grows on water. So, protecting it is really much more than just a matter of a food resource. It’s deeply, deeply tied to their identity.”

Working on tribal land

As a result, the research, which is also funded by the Institute on the Environment, took on a new dimension— partnerships with many Native American bands who depend on wild rice.

“The central tenet of this project is that we examine what our Native partners want us to examine,” said Amy Myrbo, a research associate in the University’s LacCore/CSDCO facility within the Department of Earth Sciences who has published on wild rice and sulfate with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

“Not only do they have long histories in the landscapes of Minnesota, but the Bands’ current natural resource organizations measure and manage lakes, rivers, and other ecosystems using both traditional and modern Western methods.” Myrbo noted. “In my experience, they are much more enthusiastic about using innovative methods than agencies and other resource managers.”

To gain trust and establish rapport with Indian tribes, the CSE researchers have spent weeks traveling to tribal leaders in wild rice country.

“We just really needed to listen at first,” Ng said.

In fact, for a while, Ng wondered if they would even be able to do any real fieldwork. But several tribes have proffered research and monitored sites on tribal land.

“Ojibwe tribes in manoomin [wild rice] country are enthused to be given the opportunity to work on a collaborative research project of this type,” said Eric Chapman, a treaty resource manager from Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin.

“We appreciate the research team listening to some of our oral teachings and respecting what they do not yet understand,” he said.

Sustenance for now, and the future

The groundwork coalesced into a conference earlier this year with researchers and nearly 40 tribal representatives from 12 bands and four inter-tribal organizations in Minnesota and Wisconsin who are committed to, or interested in, the study.

“The project has been very rewarding thus far, and there was lots of good discussion at the conference,” said William Graveen, a technician with the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Wild Rice Cultural Enhancement Program. “I personally came to realize that the issues we’re facing and dealing with in Wisconsin are pretty consistent across the region.”

New information on wild rice habitats, he added, can better protect this important resource.

“Manoomin has no state or county boundaries on where it will grow and provide sustenance,” Chapman noted. “We recognize it as an indicator of healthy niibii [water] and hope this project educates our future generations.”

Story by Greg Breining

If you’d like to support faculty research, visit our CSE giving page.