You, too, can translate ancient documents

Technology plus a cast of thousands open windows onto Ancient Greece

Two thousand years ago (give or take a few), a resident of Oxyrhynchus tossed a piece of papyrus onto the town's trash heap. There it lay, parched by the Egyptian climate, preserved for posterity.

Now, University of Minnesota researchers are employing technology and the discerning eyes of tens of thousands of volunteers around the world to decipher texts salvaged from that ancient trash pile.

The modern chapter of this exceedingly long story began in 1896 when British archaeologists discovered the Oxyrhynchus rubbish mounds. The find was at first unimpressive—then dazzling. It included some of the earliest copies of the New Testament, fragments of the Gospel of Thomas and other non-canonical Christian and Jewish theological writings, poems of Pindar and fragments from Sappho, parts of lost plays of Sophocles, the oldest diagrams of Euclid's Elements, a life of Euripides...as well as private letters, business contracts, tax documents, census returns, even grocery receipts for dates and olives.

"It's every kind of writing you can imagine," says Nita Krevans, a professor in the CLA's Department of Classical and Near-Eastern Studies. "And it's material we don't have for most other locations from this period."

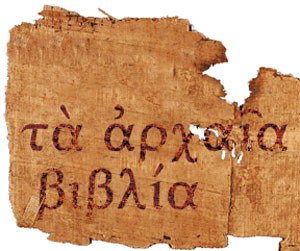

The documents may be mostly small fragments, but they are keys to vast untapped knowledge about Egyptian life from the third century BCE to the eighth century CE. Most were penned during the first and second centuries CE; they were written primarily in Ancient Greek, Egypt's official language after Alexander's conquest in 332 BCE.

So this is a story of how a city dump turned out to be an unequalled archive of ancient life and times. Of how it yielded comprehensive records of a large and prosperous city that today lies buried under the modern town of el-Bahnasa, and writings by some of the ancient world's greatest artists, scholars, and religious writers. And of how modern-day CLA scholars are part of this historic exploration.

A staggering task

After a fair bit of digging it became apparent that the very richness of the find presented a major problem. The fragments number around a half million; many are faded and torn, the antique ink abraded. In more than a century since they were discovered, only about 1 percent have been transcribed and published. While modern scholars are certainly able to read the Greek texts, even sifting through the mounds is a challenge of staggering proportion.

But a new project, Ancient Lives, is speeding up that glacial pace. It's an international, interdisciplinary collaboration involving the Egypt Exploration Society, which owns the Oxyrhynchus papyri collection; Oxford University, which stores it; and two U of M colleges —CLA via the Department of Classical and Near-Eastern Studies, and the College of Science and Engineering, which are developing technology to help translate it.

On the Ancient Lives website you can find images of hundreds of thousands of the fragments and an invitation to transcribe them by matching handwritten letters to the Greek characters that appear in a key at the bottom of the screen.

"We're basically asking volunteers to speed up the transcription process," says Marco Perale, a CLA papyrologist (papyrus expert) and postdoctoral researcher.

Citizen scientists

Ancient Lives grew out of Galaxy Zoo, a project launched in 2007 to recruit amateur science enthusiasts to help identify galaxies from images posted on the website.

Lucy Fortson, associate professor of physics and astronomy in the College of Science and Engineering, was involved with that project from its early days. "Galaxy Zoo was such a huge success that we realized there were many other opportunities to use the same process with other fields," she says.

That realization grew into Zooniverse, a Web portal that invites citizen scientists to contribute to a whole range of endeavors. For example, Zooniverse volunteers scour images of the skies for distant planets, model climate change using historic ship logs, and translate the songs of whales.

Ancient Lives joined Zooniverse last summer. Volunteers—there are already 120,000 of them, says Krevans—pore over the online papyrus images, matching individual letters to the provided set of Ancient Greek characters.

"The large majority are amateurs," she says. "Many don't even read Greek. It's a pattern-matching exercise—you just match the shapes."

Fragments range from textbook-quality treatises penned by professional scribes to nearly illegible cursive—replete with misspellings—scrawled by students writing home from school. "Handwriting is notoriously difficult," says Fortson. Indeed, identifying those shapes can be tricky—and human eyes still do a better job of it than computers.

As many as 70 to 100 volunteers may work on a single fragment. But that is just the first step in the translation process. Behind the scenes, Fortson and Anne-Francoise Lamblin from the U of M's Minnesota Supercomputing Institute are developing software to analyze the volunteers' findings and create a master transcription based on the most common responses from each volunteer transcriber.

They hope to refine the software so it can "learn" and adapt—for example, recognize the most reliable volunteers and give greater weight to their transcriptions. Eventually, software might even learn enough about the rules of the texts to fill in gaps with the most likely missing letters.

Early tests indicate that the volunteer transcribers are doing an impressive job, producing transcriptions that agree with experts about 80 percent of the time. Fortson expects to nudge that number closer to 90 percent as the software is tweaked.

Smart as the software may be, however, it by no means replaces classics scholars, so CLA's Perale and his counterparts in Oxford take over where the software leaves off. They review the consensus transcriptions, translate the text, interpret it, and determine which scraps are worthy of publication. "We want to get information on the 99 percent of the collection that has not been published so far," he says.

The project is fast gaining fans. When Theresa Chresand, a sophomore Greek major, learned about it, she immediately got hooked, now spends a lot of her free time on Ancient Lives, and has even recruited friends to join her. "Just being able to interact with the fragments has been really interesting and has helped my Greek," Chresand says. "I had no idea what papyrology was until I got involved in the project." Now she's considering it as a career option.

Meanwhile, as the Minnesota computer science team continues to refine the software, collaborators in Oxford continue to upload new images. And Perale is at work reviewing transcriptions and working on the Ancient Lives website, answering users' questions and writing a blog that involves active volunteers in the conversation.

Perale arrived at CLA in September, courtesy of a two-year Minnesota Futures Research Grant of which Fortson is the principal investigator. (Minnesota Futures is a U of M program that provides opportunities for researchers to cross disciplinary and professional boundaries.) Perale's office in Nicholson Hall is still mostly unadorned, save for a bookshelf lined with the 76 volumes of The Oxyrhynchus Papyri that have been published to date. The first one was published in 1898, the most recent just last year. Soon, he hopes, new volumes will be released, filled with translations of lost comedies from ancient playwrights and personal letters from people whose names we'll never know.

"Here we have 500,000 documents that are waiting to be transcribed and analyzed, and they hold a very big potential," Perale says. With help from around the world, he's making progress—letter by letter, word by word. "A word," Perale says, "tells a lot."

Get in on the fun—go to the Ancient Lives website.

Kirsten Weir is a science writer and editor based in Minneapolis. She has written for Discover, Salon, Psychology Today, and the American Psychological Association.

Photos by Lisa Miller

This story has been reprinted from the University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts Reach magazine with permission.