CSE student team builds first University of Minnesota cube satellite for the ISS to launch into space

Above: Successfully launched to the International Space Station on November 2, SOCRATES aims to both measure electronic accelerations in solar flares and use astrophysical signals to prove that x-ray-based navigation is possible.

Multidisciplinary Small Satellite Project will launch into orbit in February 2020

Editor's Update: SOCRATES was deployed into Earth's Orbit on Feb. 19 at 8:30 a.m. Now, students in the Small Satellite Research Group will attempt to make contact with and gather data from the CubeSat from a ground station in northern Minnesota.

October 3, 2019

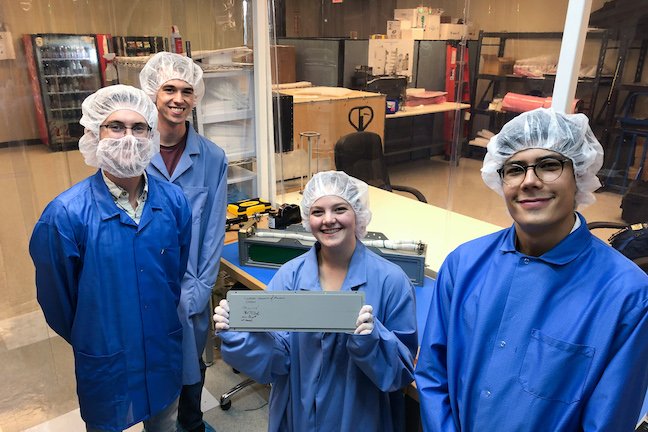

Jenna Burgett and Kyle Houser can now say their names are written in the stars—etched on the access panels of a small cube satellite in space, that is. The two College of Science and Engineering students are project leaders in the University of Minnesota's Small Satellite Research Group, an interdisciplinary team building small satellites sponsored by NASA and the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Burgett and Houser had the honor of delivering SOCRATES (Signal Opportunity CubeSat Ranging and Timing Experiment System) in person to Houston, where they handed it off to satellite deployment company NanoRacks to launch it into space for NASA. There, they had the opportunity to sign the satellite—with a NASA-approved marker, of course.

On Nov. 2, the CubeSat successfully ascended to the International Space Station on an Antares rocket, and it will be released into Earth’s orbit on Feb. 19. SOCRATES is the first small satellite built by the University of Minnesota Twin Cities to go into space.

Pitched to NASA in 2016, SOCRATES has two missions. The first involves using pulsars, or astrophysical signals, to facilitate x-ray-based navigation, a means of positioning oneself in space when GPS is not available. The second, investigating electronic accelerations in sun flares in order to understand the science behind the solar anomalies.

Once SOCRATES is in orbit, the team will try to make contact from ground stations across the country, including one in northern Minnesota—with hopes of gathering six months of continuous data from the CubeSat.

Student-led satellites

The Small Satellite lab is a joint effort established by aerospace engineering and mechanics professor Demoz Gebre-Egziabher and physics professor Lindsay Glesener. While faculty remain supervisors, the students participate in every level of the project, from grant proposal to satellite design to communicating with industry partners. Burgett and Houser are the team’s project manager and chief engineer, respectively.

“We’re trying to provide an undergraduate experience on real engineering and physics-based projects,” said Houser, a senior majoring in aerospace engineering and a recipient of the University’s Presidential Scholarship.

For Houser, seeing through a real project from start to finish is valuable experience.

“The biggest impact this has on our future careers is that you set yourself apart by just being on the project and seeing how these things operate,” he said.

“It’s the students that lead the lab and make a lot of the decisions,” Burgett added. “So, you learn through trial and error the lessons you would learn in your job after you graduate. Having those lessons learned earlier rather than later, you can go into the job field more informed.”

Burgett, a senior who is double majoring in astrophysics and physics, said this real-world experience is huge, especially for the science majors on the team.

“Especially on the physics side of things, this project helps you apply the theoretical aspects,” she explained. “Getting that hands-on experience and practical use is something I find very beneficial.”

Burgett joined the team as a freshman and started off working on the satellite’s x-ray detector, doing a large amount of data analysis and coding.

“That was huge for me because I never would have seen it anywhere else in my major,” she said. “I got a nice head start in electrical hardware and signal processing.”

Space for all

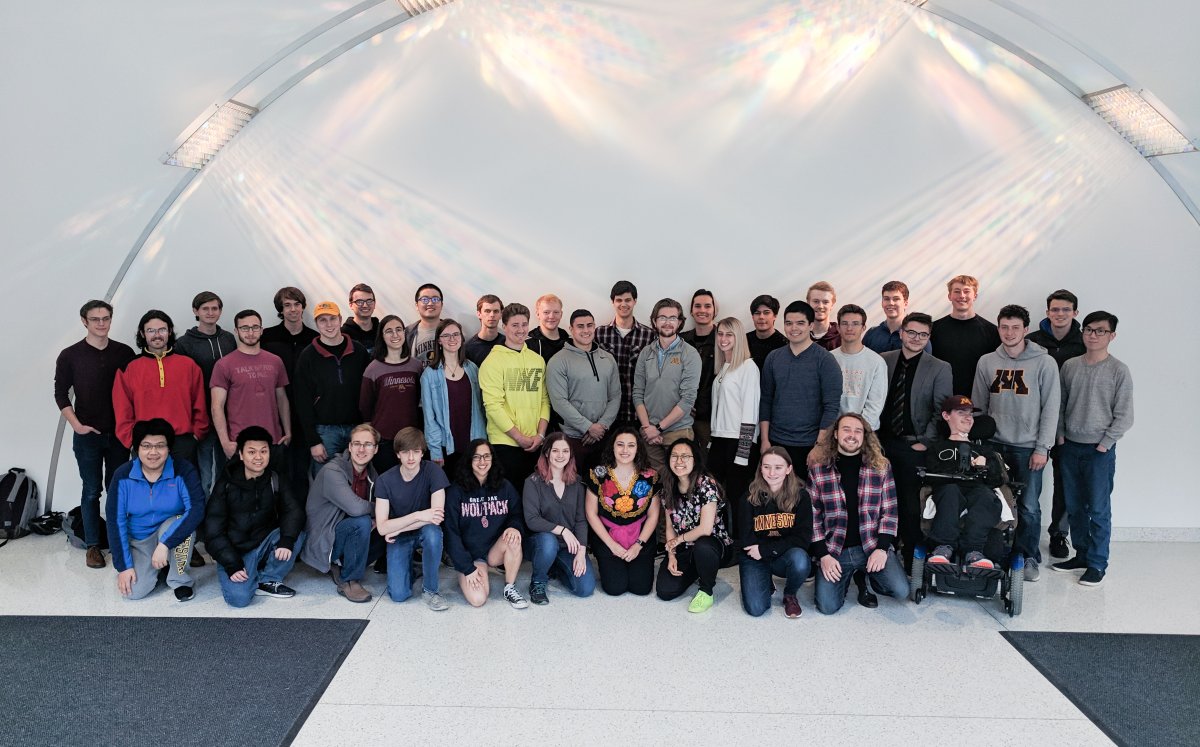

While a multitude of students have worked on SOCRATES over the years, the University of Minnesota Twin Cities’ Small Satellite Research Group currently consists of over 30 students from a wide range of science and engineering majors.

“We kind of take people from all different majors in STEM and ask, ‘What is it you want to do?’” Burgett said. “We try to help teach them, and a lot of times you get people that are really motivated and will learn those things and help bring the project forward.”

Aerospace engineering and physics remain bases for the satellite projects, but the team houses every type of student from electrical engineers to math majors. According to Burgett and Houser, this blend of science and engineering is crucial, and communication between the fields is even more important.

“Having that communication about science and engineering helps the project itself but it also helps everybody get a better product,” Houser said. “It allows the people who make the things and the people who use the things to work together better.”

For example, while scientists may value data collection more, engineers may value the more technical and hardware aspects of the project. But, Houser said finding a balance between the two is what informs higher quality projects.

Burgett added that a marriage between theoretical and applied science is exactly what employers are looking for in industry.

“Bridging that gap between science and engineering is huge,” she said. “When you come from two different learning backgrounds, you think about problems differently."

"Having those different mindsets is really beneficial, because then you get to attack the problem at different angles,” Burgett said.

Shoot for the moon—or the ISS

Beyond the work itself, Burgett and Houser agree that there’s a necessary “cool” factor that accompanies working with NASA and having a piece of metal with your name on it floating around in space.

“I’m basically jumping up and down inside all the time,” Burgett said. “I’ll just be sitting around somewhere and think, ‘You know what? That thing I worked on for years is going to be up in space soon.’ It’s unreal.”

Houser said that regardless of whether the SOCRATES missions are successful, he still views the launch as a huge achievement for the University’s Small Satellite Project.

“This team is full of very dedicated students from a bunch of different disciplines,” he said.

“There’s no way that only two people do this," Houser said. "The lab is the team, and we do a very great job at what we’re trying to accomplish. The amount of people that have cycled through our lab and done great work is incredible.”

Burgett added that their process is one of constant improvement.

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities’ Small Satellite Research Group already has two other CubeSats in the pipeline, EXACT (Experiment for X-ray Characterization and Timing) and IMPRESS (Impulsive Phase Rapid Energetic Solar Spectrometer), slated to launch in 2021 and 2022 respectively.

“All of us here are very excited and very proud of SOCRATES,” Burgett said. “We’ve learned so many lessons from this experience, and all of that experience is going to be put back into this lab. We’re already taking lessons we’ve learned and applying them to the new satellites we’re starting to work on.”

Story by Olivia Hultgren

SOCRATES flew to the International Space Station with NASA's Cygnus NG-12 mission on Nov. 2. Visit NASA's mission status website to learn more about the launch.

If students are interested in joining the Small Satellite Research Group, they can contact the team at smallsat@umn.edu.

If you’d like to support students in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, visit our CSE Giving website.