CSE’s HumanFIRST Lab helps engineer systems with people in mind

In the above image, lab director Nichole Morris leads a community workshop with representatives from Saint Paul's Public Works, District Councils, and Police Department. Photo credit: Michael McCarthy

Researchers bring a key perspective to topics from driver safety to military healthcare

November 22, 2022

If you’re wondering what the University of Minnesota’s HumanFIRST Lab does, look no further than the name. Its researchers put the “human” first—in engineering research, that is.

Housed in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, the lab specializes in human factors research, a field that combines engineering and psychology.

“What we study is the interaction between people and systems, which ends up being a very broad domain of work because almost everything includes people interacting with systems,” said Nichole Morris, research associate professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and director of the HumanFIRST Lab. “It can be people interacting with technology, a roadway, or infrastructure. Or, it could be interacting with an institutional system like law enforcement or the military.”

Most of the HumanFIRST Lab’s work revolves around transportation systems and driver and pedestrian safety, but its overall goal is to create more user-friendly systems across the board—from vehicle crash report technology to Army medic training.

Some universities place human factors research in their psychology department, but according to Morris, the HumanFIRST Lab is right where it belongs in the College of Science and Engineering.

“There are lots of opportunities for us to work with engineers who are developing or prototyping systems or products that real people would interact with,” said Morris, who has a Ph.D. in human factors psychology from Wichita State University. “You often have really brilliant designers and engineers who need support understanding how people will use their systems. So, we're really a facilitator for those needs. Our job is to use our knowledge of human capabilities and limitations to build systems with people in mind to make life safer and more enjoyable.”

Morris came to the University of Minnesota as a researcher in 2011, was named director of the HumanFIRST Lab in 2017, and was promoted to research associate professor earlier this year.

“I was looking for a good home for me that was doing a wide range of research,” she said. “I was just really drawn to the work that the HumanFIRST Lab was doing, and how many diverse opportunities there were for me to apply the different skill sets that I had.”

Putting the ‘U’ in engineering

Since its inception in 2001, the lab has built up quite a resume of projects, many of which directly impact the Minnesota community.

In 2014, Morris helped redesign the state’s vehicle crash report system to make it easier for police departments to gather accurate data on car crashes. That system is now becoming the national standard for crash reporting in the United States.

But, the HumanFIRST Lab is perhaps most well-known for working with the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) to study how drivers behave at crosswalks in the Twin Cities. This information can help the state figure out how to increase drivers’ compliance with the law and better protect pedestrians crossing the road. The researchers recently expanded this project to Rochester, Minn., to look at how drivers behaved around the city’s new autonomous shuttle, which was rolled out as a demo last year.

The researchers’ most recent project, however, diverges from the transportation industry.

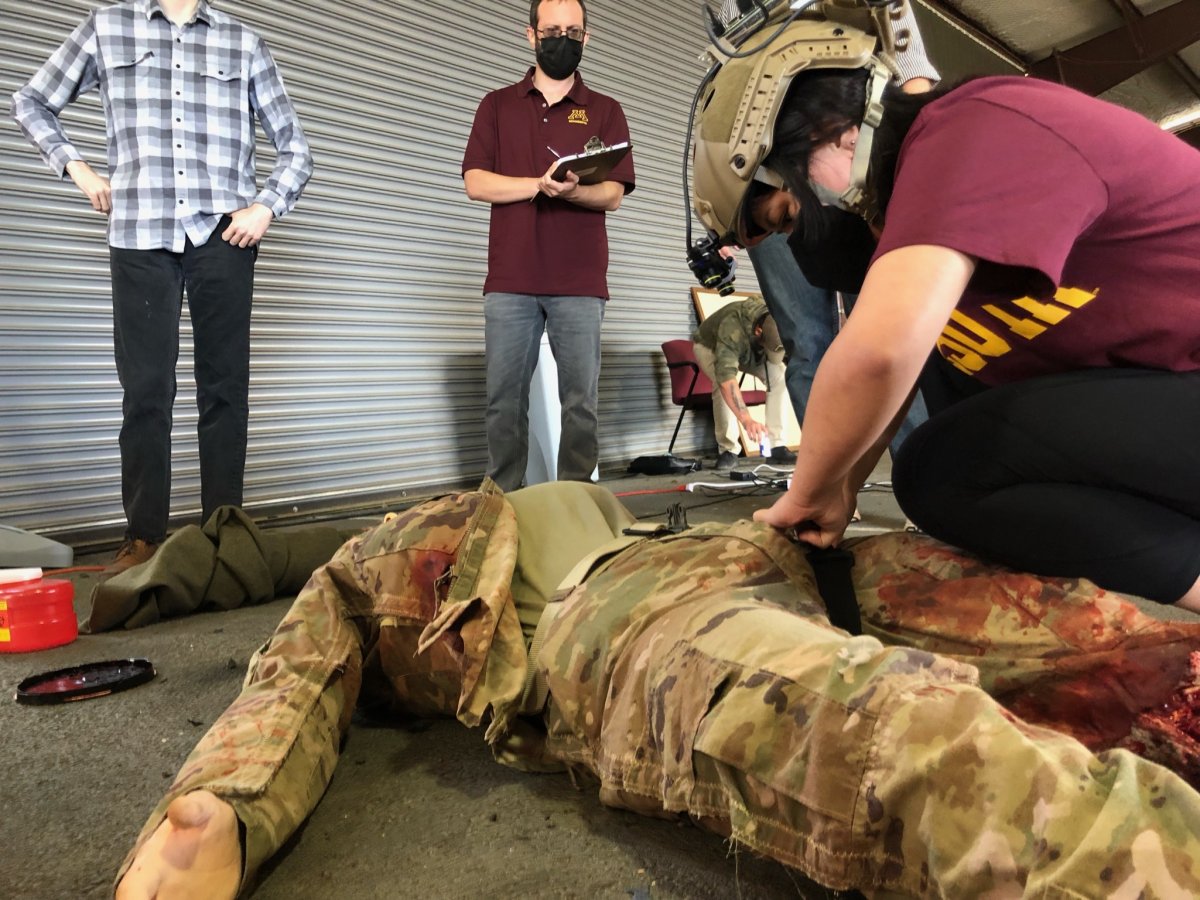

Morris and her team are working with mechanical engineering associate professor Tim Kowalewski and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) to study gender disparities in combat medicine after reports that female soldiers experience worse outcomes from the same injuries as their male counterparts.

“That’s very unnerving to hear, especially as we have women entering combat positions in our armed services,” Morris said. “We need to understand why this is happening, and what can we do to close this gap to make sure that our female service members are experiencing the same standards of care. So, we've been working collaboratively as an engineering team to try to understand what the training process is for Army medics and the tools they’re given during training.”

The researchers found that the manikins the medics typically practiced on were all based on a generic male body, so when the medics were presented with a novel female manikin, they tended to make more errors or complete procedures out of order.

For Morris and her team, this is a classic human factors problem that involves how people interact with the tools they’re given. They hope to extend their findings from the DoD research and apply it to how first responders treat female victims at the scenes of car crashes.

“That’s the beauty of human factors,” Morris said. “We’re never focusing on just one thing. We're accounting for all of these local, institutional, and systemic factors that are feeding into a problem. All of these things come together, and then we try to come up with good solutions that can combat and prevent bad outcomes.”

Story by Olivia Hultgren

If you’d like to support research in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, visit our CSE Giving website.