High resolution imagery gives new insight into emperor penguin population

Researchers report nearly 10 percent fewer birds, according to new study

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (03/19/2024)—An international team, including a University of Minnesota Twin Cities researcher, has released a first-of-its-kind new study that gives insight into the population of beloved emperor penguins in Antarctica over nearly a decade. It also provides new monitoring methodology that could help develop adaptive conservation management efforts.

Initial results of the study reveal nearly 10 percent fewer birds in 2018 compared to 2009. Scientists cannot yet explain the population trend. However, additional research should help with a better understanding of the causes—including the role of climate change.

The research article “Advances in remote sensing of emperor penguins: first multi-year time series documenting trends in the global population,” is published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Emperor penguins have been exceedingly difficult to monitor because of their remote locations, and because individual penguins form breeding colonies on seasonal sea ice fastened to land (known as fast ice) during the dark and cold Antarctic winter.

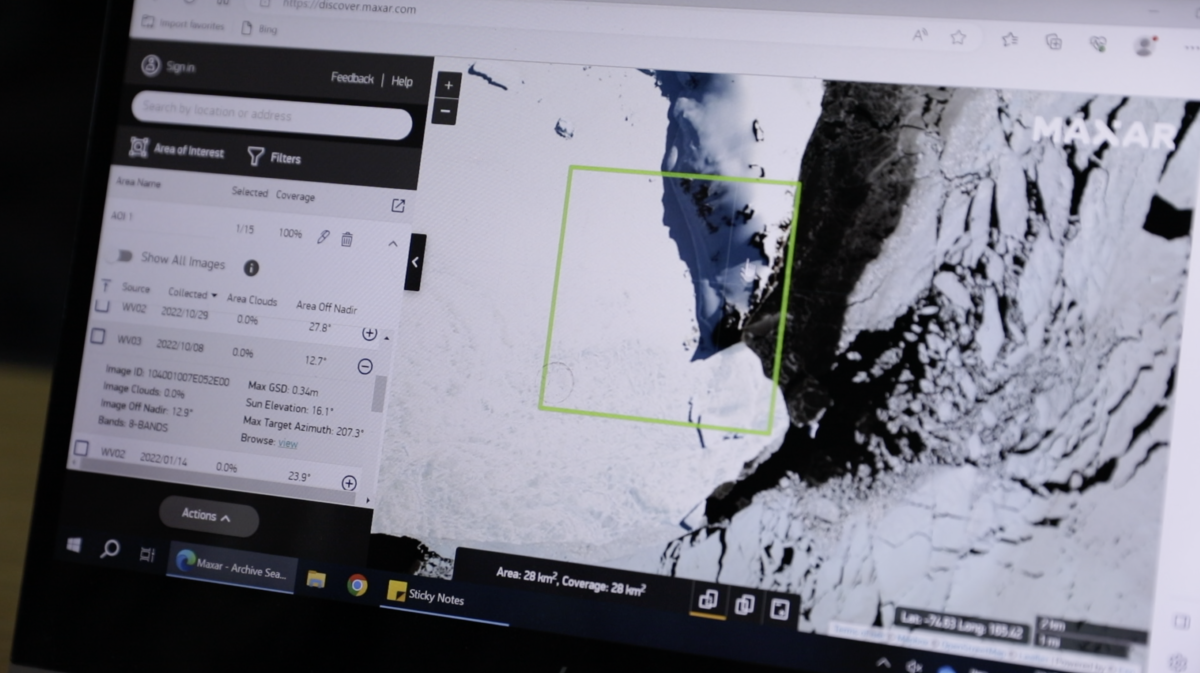

This new research incorporates very high-resolution satellite imagery with field-based validation surveys and long-term data to provide the first multi-year time series that documents emperor penguin global population trends.

“Our work documents change in an iconic polar seabird and shows how useful remote sensing can be to understand animals that live in wild places,” said journal article co-lead author Michelle LaRue, a research associate in the University of Minnesota Twin Cities Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and an associate professor at University of Canterbury in New Zealand. “In a rapidly changing world, we have to constantly push the envelope to combine new approaches with tried-and-true methods if we want to understand the consequences of that change, especially in places we cannot get to.”

LaRue said combining satellite images with animal tracking, ground observations and molecular tools (like genetic analysis) will be needed if they want to fully understand mechanisms to describe some of the changes they observe.

During the course of the study, researchers detected several new colonies, bringing the total to 66 known colony locations. It is now highly probable that most emperor penguin colony locations have been detected, with about half having been detected with satellite imagery, according to the paper.

In addition, the research identified the East Indian Ocean and Weddell Sea areas of Antarctica as being the two sectors of the continent where there is the greatest probability of declines in regional populations of emperor penguins. These are locations where the extent of fast ice generally has decreased in recent decades. Emperor penguins primarily form colonies and rear their chicks on fast ice.

“What we did in this paper, and through international collaborative research, was to develop the state-of-the-art approach to monitoring emperor penguins across all of Antarctica, including in remote places that are inhospitable to people,” said journal article senior author Stephanie Jenouvrier, senior scientist in the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Biology Department. “Having the very high-resolution satellite imagery is a breakthrough in our understanding of the spatial distribution of emperor penguins, and having this global population trend is very important for conservation,”

Jenouvrier noted that the computer modeling takes into account many processes and uncertainties related to penguin population and life history.

“Although we cannot yet clearly attribute this penguin population trend to any particular mechanism such as climate change, there is an accumulation of evidence that the environment is changing and it does not seem to be an environment where penguins are going to endure,” Jenouvrier explained.

The journal article authors said that with this new methodology, there is now a way forward to assess the population status and trends of emperor penguins at a global scale, which provides an invaluable tool for adaptive conservation planning in a changing Southern Ocean.

Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation, NASA, the French Polar Institute Paul-Émile Victor, Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in the Helmholtz Association, World Wide Fund for Nature (UK), and the German Research Foundation.