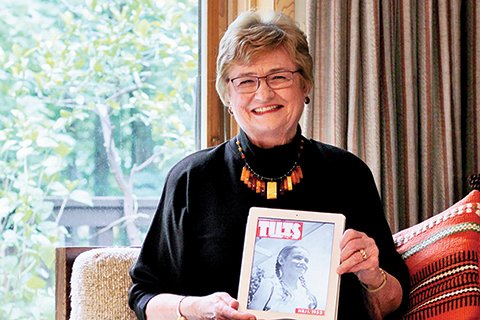

Ieva Ogriņš Hartwell: Displaced by World War II

Chemistry alumna finds a home and success in the United States

March 25, 2018

Sometimes immigrants carry perspectives that allow them to see possibilities others don’t.

As a girl from Latvia, Ieva Ogriņš Hartwell (Chem ’63), never questioned her interest in math and science. In 1963, just after graduating with distinction from the University of Minnesota, she spent a summer abstracting fluorocarbon research reports at 3M in a program for top students on their way to graduate school.

She was the only woman among more than 100 men.

“In Europe in general—not just Latvia—women went into the sciences,” Hartwell said. “Think of Marie Curie!”

“I don’t know what it was about U.S. culture as it developed that women were discouraged from those fields, but I never felt that science was closed to me,” Hartwell said.

“And my mother encouraged me,” she added.

Life in a new country

Hartwell’s mother, a pharmacist widowed in World War II, was part of the exodus of educated professionals who fled Latvia in 1944 after the Soviet occupation. After spending five years in camps for displaced people in Germany, eight-year-old Hartwell came to the United States with her mother, older brother, and grandmother.

They were among the 40,000 Latvians who were allowed to immigrate to the United States between 1949 and 1951.

They stayed briefly with distant cousins in St. Paul, Minn. while Hartwell’s mother found work. (Her mother later got a chemist job at General Mills and her uncle, Egolfs Bakuzis, earned a Ph.D. in forestry at the University of Minnesota, where he became a professor).

Hartwell excelled in high school and graduated tied for first in her class with another Latvian girl.

Beating the odds

Even so, her school counselor refused to submit her application to what was then the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Technology, saying, “They don’t want girls.”

Hartwell persevered and received two scholarships, which she stretched to cover tuition by living at home and working summers.

“There was quite a bit of resentment about so many World War II refugees,” said Hartwell, who is sympathetic to today’s refugees.

“People worried about immigrants taking jobs and taking scholarships,” she explained.

Hartwell earned a Ph.D. in inorganic chemistry in 1969 from the University of Illinois, where she met her husband, another Ph.D. chemist. When he landed a job at Indiana University Bloomington, nepotism rules prohibited hiring her.

“I thought maybe I could get a post-doc in another department,” Hartwell explained. “They said ‘no,’ but that I could take the typing test, because as a faculty wife, I could only get a job as a secretary.’’

This roadblock ultimately steered her toward a career in information technology.

Finding her niche

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had just created a center at Indiana to facilitate technology transfer by sharing its vast databases with the public. This was decades before the Internet allowed researchers to pull up the full texts of scientific articles at their desk, and computerized searches were complex and cumbersome.

Hartwell was hired to help scientists comb through scholarly articles for the information relevant to their work.

She stayed in information technology as the field grew, through raising two sons and following her husband’s job—first to Massachusetts and then to Midland, Mich. She has supported CSE through contributions to the Akerman Memorial and Robert C. Braskel funds since 1980.

Hartwell worked 20 years as a consultant and then 11 years as a product engineer for Dialog, an online information service that licensed hundreds of databases.

Her chemistry background allowed her to handle chemistry, engineering, and patent databases, writing more than 100 user manuals and ensuring that programmers created the features that made user searches deliver precise and relevant results.

“Anybody can do an Internet search and get five million answers,” she said. “But five million answers aren’t what you want. You want the 10 that really answer your question, or even the one.”

Story by Maja Beckstrom

Related stories