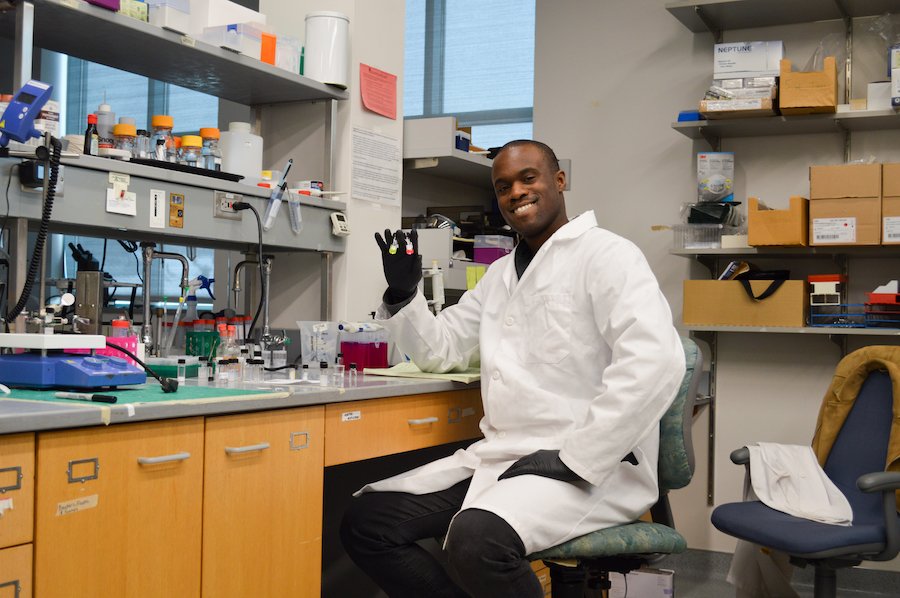

The sky’s the limit for biomedical engineering Ph.D. student Marcus Flowers

The researcher’s work involves everything from 3D printing cardiac tissue to creating vessels to deliver vaccines

March 21, 2023

Marcus Flowers often gets asked what his research focuses on. Is it 3D printing? Cancer therapies? Stem cells? Drug delivery? His answer: Yes. All of that, and more.

The University of Minnesota biomedical engineering Ph.D. student builds and tests materials that can be used to deliver different drugs and treatments into the body. For example, a pill that encases medicine or the liquid solution in which a vaccine is stored. He works in tandem with College of Science and Engineering professors Chun Wang, whose lab develops polymer-based healthcare technologies, and Brenda Ogle, whose team focuses on regenerative stem cell therapies.

Because the two professors often collaborate on these research topics, Flowers gets to work on a wide range of projects with seemingly infinite applications—and all of them could one day save lives.

“One of the things that I enjoy the most about my research is the idea of the possibilities,” said Flowers, a recipient of the Boston Scientific Biomedical Engineering Fellowship. “It really feels like the sky is the limit. There’s never a shortage of problems that we’re interested in trying to solve, and that's really what makes the research exciting.”

Cutting-edge research

Flowers grew up in the eastern suburbs of St. Paul, Minn. After high school, he left for Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in upstate New York with the intention of eventually applying to medical school.

But, he ended up falling in love with biomedical engineering and returning to Minnesota to pursue a Ph.D. after his undergraduate studies.

“Growing up around the University of Minnesota, I didn't appreciate how much of a standout institution it was,” Flowers said. “It wasn't until I left and saw other schools that I realized that the U is actually really good at developing people to work on these technologies and creating a good environment for fostering new ideas. I realized that I could do this really cool stuff, and I don't have to go halfway across the country to be involved in it.”

One of Flowers’ main projects at the U of M is 3D printing human heart models to test the delivery of drugs. These models can eventually be used to improve future treatments for cardiac conditions, or even be translated to apply to diseases like cancer.

His work is part of an umbrella project out of Wang’s lab called CAPRO, which focuses on developing materials that can deliver targeted therapies exactly where they need to go in the body.

Their technology has the potential to minimize the side effects that usually stem from drug treatments, and create a more universal system that can work for delivering multiple types of medicine. Wang’s lab is currently working with the Mayo Clinic to use the technology to stabilize vaccines while they’re in storage.

“Biomaterials are really foundational to all medical technology challenges,” Flowers explained. “If a nail is a problem and a hammer is a solution, instead of finding a unique solution for one nail, we're more interested in developing a very efficient hammer that can tackle all sorts of problems. That underlying simplicity is what's foundational to our lab culture—finding simple, efficient solutions to complex problems.”

Guiding the next generation

Flowers cites the Department of Biomedical Engineering’s positive, collaborative environment as a key driver of this research.

Through the department, he and a few other U of M students and researchers were able to attend last year’s BME Rising Scholars Conference—a gathering of biomedical engineering students, researchers, and faculty from across the Midwest. There, they listened to lectures ranging from how to manage your social media as a researcher to how to get more diverse voices involved in STEM.

“It was a great conference for personal development, but it was also grounded in really impressive science,” Flowers said, “and really impressive, diverse sets of professors and researchers who understand that as we grow and develop in science, we need a lot more diverse voices. We need more people actually speaking out about things that they see as challenges because it's not going to be something that everybody sees.”

After his Ph.D., Flowers hopes to either stay in academia and become a professor or work in science policy for the government.

“Ultimately, I want to guide research in a way that's equitable, provides a good education for people, and assists the most people with the fewest resources,” he said. “So, do I want to do the work myself and ask someone else to fund me, or do I go and be the person who decides to support other people’s ideas? I'm interested in being on either side of that equation.”

Story by Olivia Hultgren

If you’d like to support students and programs in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, visit our CSE Giving website.