Science behind the scenes

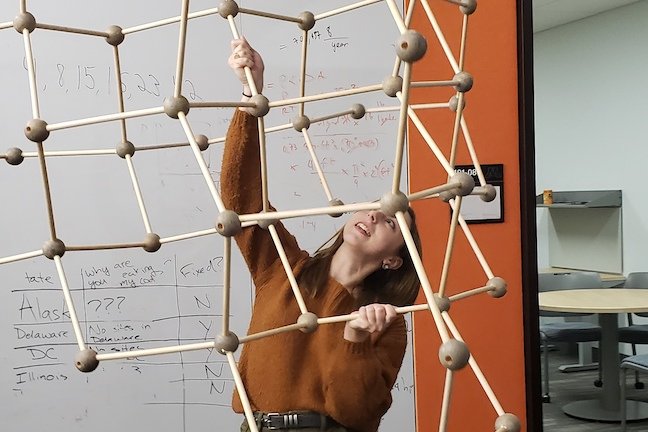

Above: Student Nora Loughlin assembles an assortment of atoms to exhibit what makes gemstones shine.

Photo credit: Jen Taylor

CSE students create gemstone exhibit inspired by visiting Northrop ballet

February 18, 2020

What’s in an emerald, exactly? And what is it that makes these gemstones sparkle? College of Science and Engineering students in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences’ Outreach Through Science and Art (OSA) have the answers.

On Feb. 22 and 23, OSA collaborated with Northrop to showcase larger-than-life-sized models of the atoms that make up gemstones. Their exhibit accompanied “Jewels” by Ballet West, a full-length ballet inspired by the beauty of the precious rocks.

“‘Jewels’ is a really interesting ballet, because we think of gemstones as jewelry that’s associated with fancy, luxury objects,” said OSA founder Jen Taylor, an earth science Ph.D. candidate and recipient of the college's Forrest Fellowship. “But in their most essential state, they’re just another part of the earth. As earth scientists, we thought this would be a very interesting thing for us to look into.”

Made up of both undergraduate and graduate students, OSA aims to teach both people at the University of Minnesota and the wider community about the science behind art.

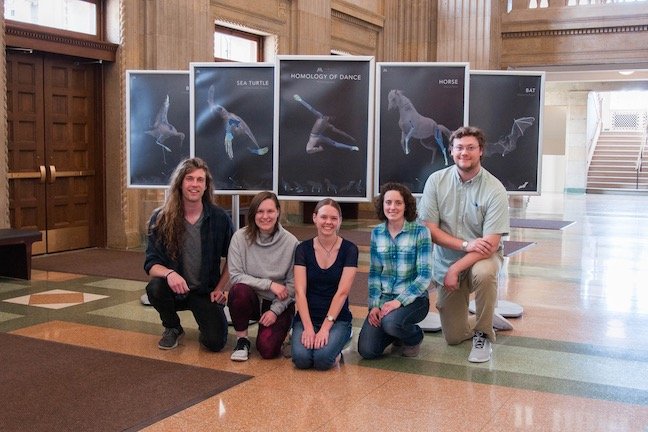

The OSA members also worked with Northrop staff last fall to create an exhibition that used seismometers—typically used to measure the velocity of earthquakes—to track dancers’ movements. In addition to creating educational projects surrounding Northrop programs, the group also facilitates a discussion series with local artists and works with them to give scientific context to their creations.

The students’ gemstone exhibit was on display in the Northrop lobby during both "Jewels" performances Saturday, Feb. 22 and Sunday, Feb. 23.

In this Q&A, Taylor talks about the group’s recent projects and why she thinks it’s important to bridge the gap between science and art.

This spring, you worked with Northrop on “Jewels.” Can you tell us more about that?

What’s cool about “Jewels” is that it’s considered one of the first truly abstract ballets—it doesn’t have a storyline. It’s just inspired by the shapes and colors and essence of these gemstones. When you look at the gemstones and ask yourself what it is that makes them so special, you realize it goes down to the very atomic, fundamental level. It comes down to what kind of atoms are in the stones and how those atoms are arranged.

We thought, what if we take these tiny structures that make these stones so unique, and blow them up so that people can see them. That’s why we’re building these human-sized models of these atomic structures. It’s a lot easier to understand how to symmetry of the atoms is affecting how the light is going through, and that’s what makes them sparkle.

You started OSA in 2017. What made you want to showcase this connection between science and art?

I’ve always been interested in both of these things. I double majored in undergrad in English and earth sciences, so I’ve always kind of had my hands in both sides of these things. When I got here, I saw that a big part of research is having a broader impact and thinking about what it’s doing to help the community. I figured here’s an opportunity, a unique niche, that I could potentially fill and use my own passion to bring these two worlds a little bit closer together.

You also worked with Northrop last semester, using seismology equipment to track the movements of dancers. What was the idea behind that project?

We like to use these sorts of performances as springboards to tie them back into something we’re working on or something we’ve learned about. [Last fall’s] performance was called “Pixel” by Compagnie Käfig—the group is very interested in projections and dancers interacting with a virtual landscape, and it had us thinking about how movement is translated between two dimensional and three-dimensional space. For example, it’s very different to watch a video of a dancer than seeing a live dancer in three dimensions.

We ended up making a motion capture device, realizing that a lot of the same programming that goes into the seismometers we use to record earthquakes can be put on a dancer.

And whether you’re recording the movement of a dancer in three dimensions or recording the movement of the earth in three dimensions, you’re doing essentially the same thing.

Part of what OSA does is make the science behind art visible to the wider community. Why do you think that’s important for people to see?

I think especially in this day and age, there are a lot of hot topic science issues out there, whether it’s climate change or GMO foods or how we’re using our earth’s resources. If people want to be able to make informed decisions and understand how we’re interacting with science to make our community and our world a better place, it’s important for them to have inlets to the science community and understand how science works, who’s doing the science, and how the science is being done. Then, it’s also important for scientists to learn how to communicate with the general public and how to have this dialogue back and forth to improve transparency.

What have you learned from talking to local artists about how science and art impact each other?

It’s been a really eye-opening experience. I think one of the things that really struck me from talking to these artists is that we’re approaching these ideas from different directions. It’s increasing my mental flexibility in a way. When we think about these issues, it’s not just from a science standpoint, but the artists are asking these questions like, how does this make me feel? How does climate change influence my mental health? How is it affecting interactions between human beings?

I think that’s something that’s important for scientists not to lose. We try to be objective, but if you lose that sense of “What does this mean to me as a person?” you can lose that connection with other people, and you can lose that connection with yourself.

Story by Olivia Hultgren

To learn more about OSA, visit the student group’s website.

Learn more about “Jewels” on the Northrop website.

If you’d like to support student organizations at the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, visit our CSE Giving website.