University of Minnesota’s Knowledge Computing Lab turns location data into time-saving tools

Photo credit: Olivia Hultgren

Technology from Associate Professor Yao-Yi Chiang’s research team could reduce human labor and speed up map analyses

October 28, 2022

Spatial data—or information with a location attached to it—is all around us. When you take a photo with your smartphone, it records the location the photo was taken. Everywhere you set foot has a unique set of GPS coordinates. Even the products we buy at the store include labels or a barcode embedded with the manufacturer or brand’s address.

Researchers in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering (CSE) are working to harness this data not only to glean information from it, but also to transform it into tools that can solve real-world problems.

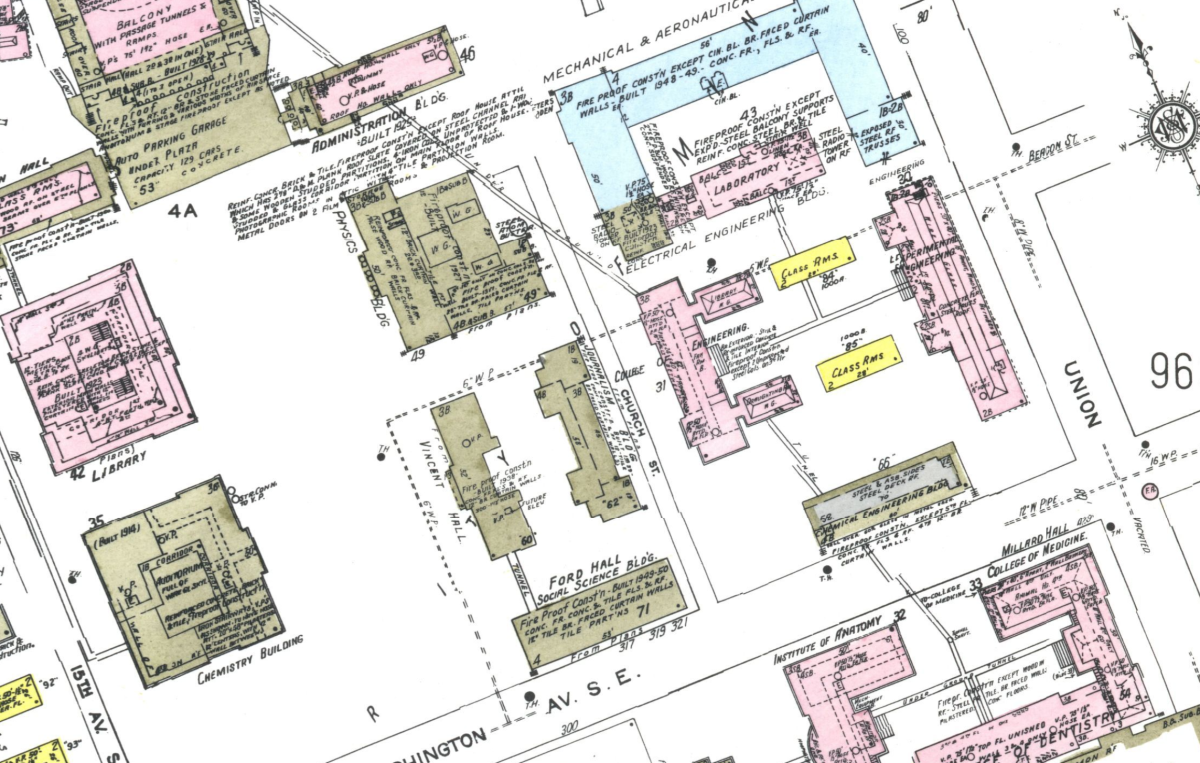

One of their current projects has turned nearly 60,000 historical maps into unique, relevant information that benefits research in a wide range of fields including demography, landscape ecology, biogeography, history, and economics.

“What we do is build machine learning models that can leverage and work well with spatial data,” said Yao-Yi Chiang, an associate professor of computer science and engineering who runs the UMN Knowledge Computing Lab.

“We’re working with data from lots of different sources and maps. Sometimes it’s images, and sometimes it’s time-series data with a location dimension. Our overall goal is figuring out how we can take all of this data that’s in different formats, and put it all together so that the machines can learn from it.”

In addition to the historical map project, Chiang and his team of graduate students and researchers use these machine learning techniques for a wide range of applications, including predicting air quality and analyzing city commutes.

Decoding history

Historical maps contain a lot of information that Google Maps doesn’t—they can help researchers study places that don’t exist anymore, find geographic features like the locations of minerals in the earth, and analyze fine-scale changes over time. However, it’s difficult to search databases of historical maps for specific locations or features since they’re all scanned images with very few tags to describe what’s on them.

Chiang and his students are working with David Rumsey, a historical map collector who has built a free database of cartographic images, to solve this problem.

The researchers have developed a technology called mapKurator that uses a machine learning model to detect and interpret text on the scanned images in Rumsey’s collection. Their system makes it easier for historians and researchers to search for items such as land formations or city names within the maps.

“Historical maps store useful information that is hard to obtain from elsewhere,” said Zekun Li, a senior computer science Ph.D. student in Chiang’s lab.

“The models we have developed can greatly reduce human-labor costs and speed up map-related analyses, which will help us better understand what was happening in the past.”

Li has been working with maps for years now and even won an award from the British Cartographic Society for creating an application that synthetically generates historical-style maps from current open map data. She’s leading an all-woman team of computer science Ph.D. students on the David Rumsey map project.

“Historical maps are both beautiful and mysterious,” said fifth year Ph.D. student Yijun Lin, whose work focuses on building a text spotter for detecting and recognizing words on the maps. “[With this project], I have been able to learn many advanced techniques, explore state-of-the-art approaches, and identify the limitations on processing historical maps, which is challenging and exciting.”

Lin, like the other student researchers in Chiang’s lab, were drawn to the mapKurator project because of the spatial science applications—and the opportunity to work with little pieces of history.

Second-year Ph.D. student Min Namgung enjoys the research because she’s a part of something bigger—developing a digital technology that can help researchers in the real world.

“I work on post-Optical Character Recognition in the Rumsey map project, which processes and extracts useful information from the historical map images,” Namgung said. “This is not only contributing to the new field of study, but it’s also preserving the information correctly for future use.”

“We’re building a smarter AI that can assist human's jobs better. I like discovering something humans cannot see directly, and the whole process is interesting for me.”

Jina Kim, a second-year Ph.D. student on the team, joined Chiang’s lab because she wanted to use computer science to tackle real-world problems. After she graduates, she hopes to use the skills she’s learned in the University of Minnesota’s Knowledge Computing Lab to inspire future students in academia.

“Our lab has lots of female graduate students, which makes me feel proud of facilitating diversity, equity, and inclusion of women in the computer science field,” Kim said. “I look forward to continuously contributing to the research community and our society and fostering the next generation as an educator, and I firmly believe my journey in the Knowledge Computing Lab will help me achieve these goals.”

Story by Olivia Hultgren

If you’d like to support students and research in the University of Minnesota College of Science and Engineering, visit our CSE Giving website.