Interfaces Volume 2 (2021)

Essays and Reviews in Computing and Culture

Interfaces publishes short essay articles and essay reviews connecting the history of computing/IT studies with contemporary social, cultural, political, economic, or environmental issues. It seeks to be an interface between disciplines, and between academics and broader audiences.

Co-Editors-in-Chief: Jeffrey R. Yost and Amanda Wick

Managing Editor: Melissa J. Dargay

+

2021 (Vol. 2) Table of Contents

Before the Byte, There Was the Word: The Computer Word and Its Many Histories -- J. Rodgers

Early “Frictions” in the Transition towards Cashless Payments -- B. Bátiz-Lazo and T. R. Buckley

Top 10 Signs We Are Talking About IBM’s Corporate Culture -- J. Cortada

NFTs, Digital Scarcity, and the Computational Aura -- A. Vee

Everyday Information Studies: The Case of Deciding Where to Live -- M. Ocepek and W. Aspray

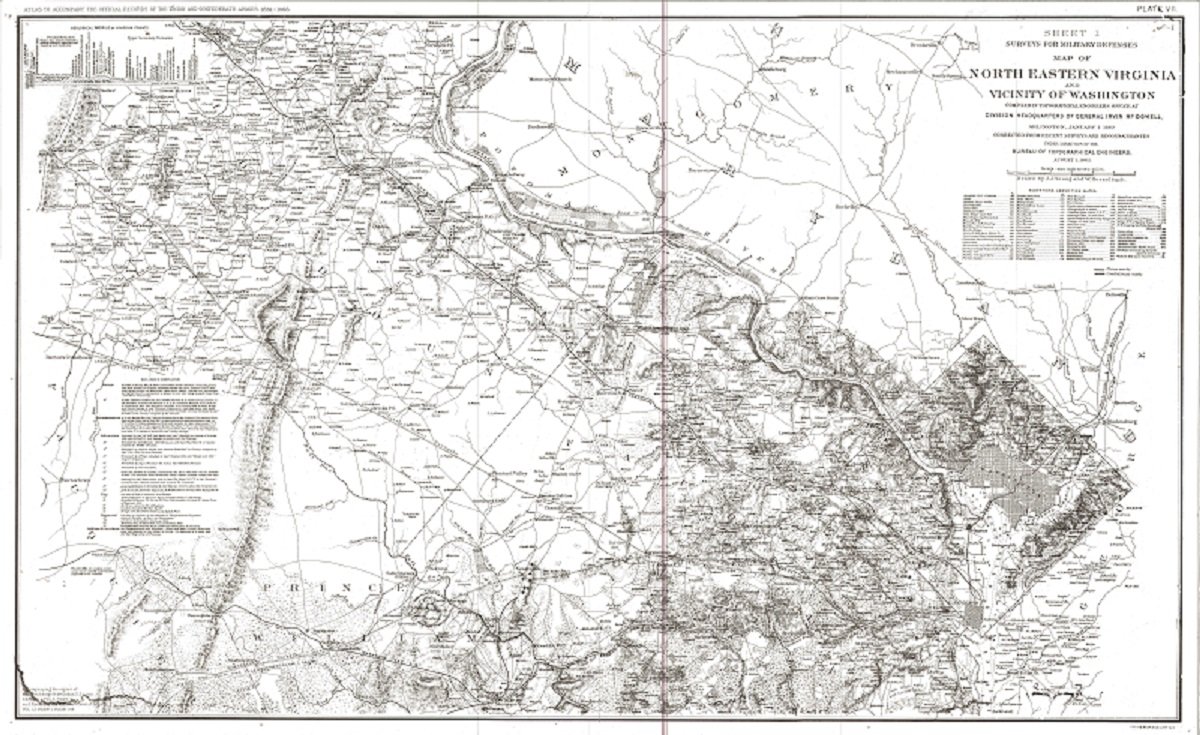

The Cloud, the Civil War, and the “War on Coal” -- P.E. Ceruzzi

Before the Byte, There Was the Word: The Computer Word and Its Many Histories

Johannah Rodgers

Abstract: Tracing and documenting the genealogies of what, in the twentieth century, will become known as “the computer word,” this article explores the importance of the term to the histories and presents of digital computings, the technical and rhetorical functions of verbal language involved with its emergence in the mid-twentieth century U.S., and the import of term’s currency in discourse networks forged across industry, government sponsored university research initiatives, and popular media.

What We Know

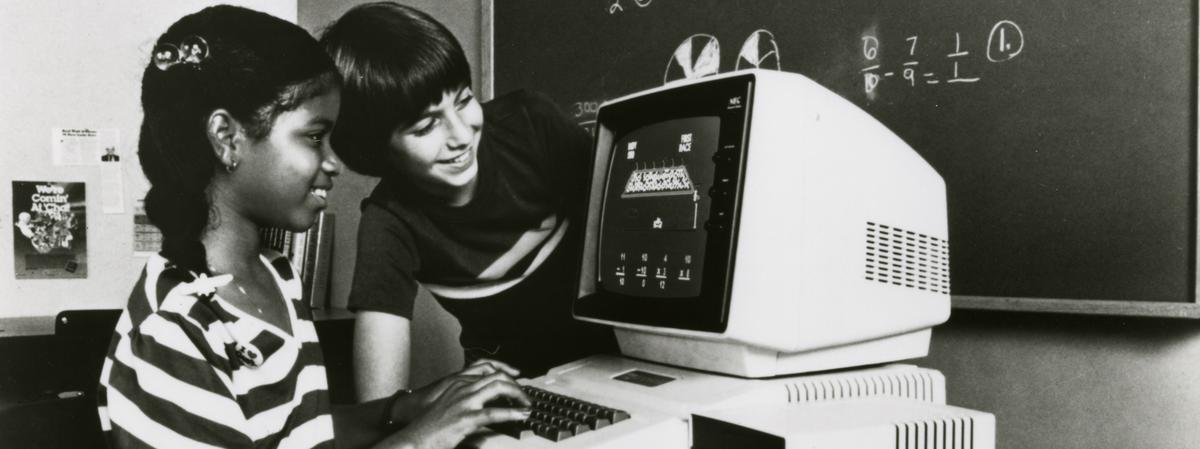

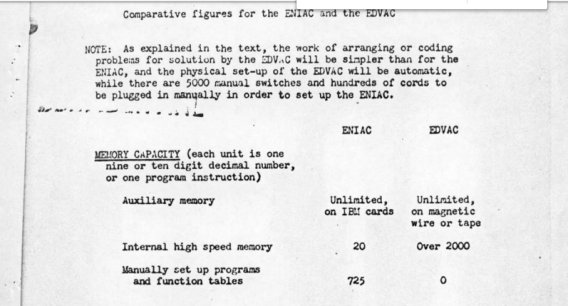

Unlike the terms bits and bytes, the computer word, which is defined by the IEEE as "a unit of storage, typically a set of bits, that is suitable for processing by a given computer," (Illustration 1) has not yet become part of popular discourse. Instead the term remains a technical one, familiar to every computer scientist and technician but not to the average consumer. Also unlike the terms bits and bytes, the origins of which have become part of the print record (bits is said to date from a January 9, 1947 Bell Labs memo drafted by John W. Tukey and byte from a June 11, 1956 IBM memo drafted by Werner Bucholz) (Tropp), those surrounding the computer word have not been well documented in either the histories of computings or fields related to it, including writing and media studies. Delving into the histories of computings archive, it is possible to identify a narrow time frame in which the term begins its emergence, sometime between late spring 1945, when John von Neumann drafts his notes that will later be referred to as the "First Draft of the EDVAC Report" and September, 1945, when J. Presper Eckert, John Mauchly, et al., compile their report entitled "Automatic High Speed Computing: A Progress Report on the EDVAC." Yet, the story of the "computer word" is, like many in the histories of computings, neither a classic origin story nor one with a sole author/inventor or single conclusion. Rather, it is collaboratively authored, recursive in its structure, and has implications that, I believe, are only beginning to be fully explored.

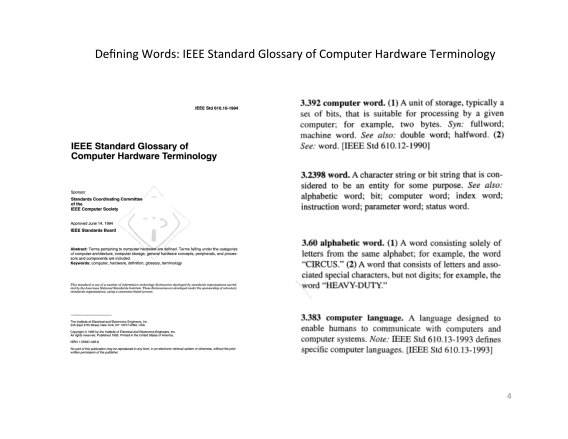

Every electronic computational machine since the ENIAC, the first fully electronic computing project in the U.S., has been described as having a "word size" and as containing a certain number of “words.” Acting as an interface between hardware and what will later become known as software, the computer word becomes one of the building blocks for machine and programming languages. It is one part of the process that enables hardware and the instructions controlling it to communicate and "understand" one another. Technically, choosing a computer word's "word size" is one of the earliest steps in chip design and, metaphorically, the computer word can be said to function as a word does in "telementational models" (Harris) of human to human communication: it allows for information to be transmitted and exchanged according to a "standard" meaning. While, in human communication, verbal words, i.e., those spoken or inscribed by humans, rarely maintain a fixed meaning, in machine communication, the computer word and the bytes and bits that will later be said to compose it have been, over time, made to adhere to such standards. Figuratively, if bits can be said to be the millimeters of digital electronic computers and bytes the centimeters, the computer word can be said to function as the meter.

Despite the technical significance of the computer word to the historic and current functions of digital electronic computers, documenting its histories is, for several reasons, anything but straightforward, in part because of the complexities of the EDVAC project itself, in part because of the later depictions of the EDVAC project in relation to projects predating it, and in part because of issues related to the histories of computings archives. Unlike the ENIAC, the EDVAC project unfolded during a time of transition from war-time to post-war based funding priorities for the U.S. military and from university-focused to industry-focused research and development initiatives. As a result, it is one that continues to provide scholars with a wealth of material and issues (technical, economic, political, and socio-cultural) to consider in relation to other electronic and electro-mechanical computing projects in the United States. The EDVAC project was, as Michael Williams has clearly documented, a fraught one and produced a machine that may actually have only been operational for a very short time and differed considerably from initial design documents. Further, recent research related to the ENIAC project by Haigh, Priestley and others, has emphasized the similarities rather than the differences between the ENIAC and EDVAC projects and called into question the portrayal of the "Von Neumann" architecture as the invention of von Neumann or a clear departure from the architectures of earlier "computing" projects in the U.S.

The availability, accessibility, and reliability of documentary archival materials also all play roles in how the (hi)stories of the computer word can be told. Just to point to two selected examples related to my research for this project, the digital copy of Eckert and Mauchly's "Automatic High Speed Computing" report available in the archive of the Museum of the History of Computing is an excerpt of the complete report. While this particular copy is valuable to researchers since it is from the archive of Donald Knuth and contains his notes, at present, no complete digital copy of the report exists that is publicly accessible. It was, in fact, only through the very generous support and assistance of the University of Pennsylvania Libraries Special Collections that I was able to remotely access a digitized copy. The existence of as yet uncatalogued materials raises other issues unique to the histories of computings archives. As a result of his ongoing research involving the Goldstine papers at the American Philosophical Association archive, Mark Priestly has drawn attention to manuscripts and unpublished lecture notes with significant implications for how not only specific terms, including the computer word, are interpreted but to other topics, such as how Turing's work may have been used by von Neumann.

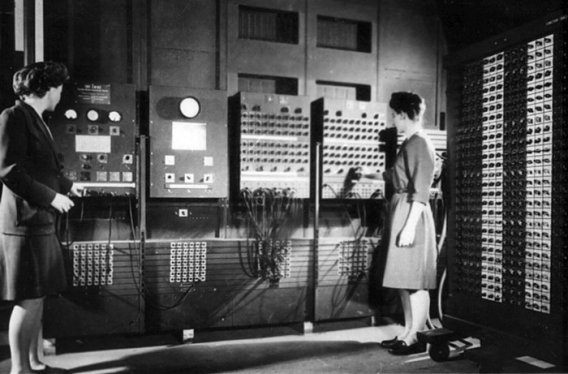

While the paper trail documenting this term "computer word" will be for some time still unfolding, what we do have currently are paper traces documenting its evolution from a term with several different functions as a rhetorical device to a technical term and finally to a technical standard. The September, 1945 "Progress Report on the EDVAC" appears to be the first time that the term “word” is used in an official document and proposal. Attributed to von Neumann in a footnote (Illustration 3), the term "word" (without quotation marks!) is introduced in a manner with more than slight Biblical overtones: "each pulse pattern representing a number or an order will be called a word*" (Eckert, et al.) In the earlier, June, 1945 Draft EDVAC report, von Neumann refers to the unit that will later be referred to as a “word” as a “code word," a term that references the operations of telegraphic machines (Priestley) and also likely the “codes” contained on the punched cards used to feed program instructions to early automatic calculators, including the ENIAC and the Mark I. Although there are references to a/the "word," "words," and specific types of "words," i.e., logical words, machine words, instruction words, control words, in documents throughout the 1950s, the earliest mention of the term "computer word" in all likelihood appears later, around 1960 (Stibitz, COBOL Report).

What We Are Still Learning

These findings reveal some useful insights into both what we know and to what we are still in the process of learning about the histories of computings and the roles of verbal language, linguistics, and language education in them.

As Nofre, et al., emphasize in their 2014 article "When Technology Became Language," the mid-1940s represent an important inflection point in how electronic digital computers are being conceived and discussed as "understanding" and engaging with language. The introduction of the term "word" to describe the operations of the EDVAC architecture appears to be one part of the discursive and technical transformation of high speed automatic calculators to general purpose digital electronic computers and to language processing (if not yet language possessing) machines. One of the key differences between the ENIAC and the EDVAC was the addition of new types of electronic storage media and its use for not only storing but manipulating codes “internally” to instruct the machine (Burks). One part of the external memory in the ENIAC, as Eckert explains it in his first Moore lecture, was “the human brain” (116). The ENIAC was a decimal-based calculator and required significant input from skilled human operators in order to function. Both issues are noteworthy because part of the story of this metaphor of the word has to do with its emergence at the same time that there is a moving away from human to machine readable writing systems (decimal to binary) and communication and storage media (wires to pulses; cards, paper, and human brains to short and long tanks and mercury delay lines). In a Turing complete machine, the machine must have some way of representing its own operations; both the ENIAC and the EDVAC had this capability. However, one major difference between these two machines was the manner in which instructions were represented and communicated so the machine could “understand” them. With the ENIAC, wires were used as the system of notation; with the EDVAC, the alphabet became another system of notation (Alt).

These paper traces from the 1940s also underscore the collaborative environment in which military funded research projects were being developed and documented in the U.S. While I am not suggesting with this term "collaborative" that in such an environment everyone was acting communally or even getting along while they worked together, I am arguing that fluidity and responsive improvisation are evident both in the discourse and the technical systems being described. What this means to documenting the genealogy of the computer word is that if the neologism is to be attributed to von Neumann, it would be necessary to put quotation marks around the terms "computer word" and "von Neumann" to indicate that both are names applied retroactively to fix the meanings of phenomena that were still emergent when placed in their specific historical contexts. Neither the "computer word" nor what is now still frequently referred to as the "Von Neumann Architecture" emerges fully formed as a concept or technical standard in 1945 when von Neumann drafted his notes for the EDVAC project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, referred to the unit that will be used to communicate data and instructions in the EDVAC project as a "code word," and handed his notes to one or more secretaries to type up and possibly reproduce and circulate (Williams).

The absence of a single author or origin story for terms like the computer word reinforces the importance of analyzing the rhetorical contexts in which the word choices of von Neumann/"von Neumann" and others are made, as well as the processes of exchange and circulation of these terms (Nofre, Martin). Paul Ceruzzi's recent article in this journal about the myths of immateriality surrounding the natural resource intensive reality of "cloud"-based computing is one example of the power of names to shape discourse and its receptions (Ceruzzi). Another example relates to the complexities involved in attempts by Tropp to depict the emergence of the term "bit" as a story with a single author. As the multilayered documentation presented in Tropp's article makes clear, there were many contributors to the creation of the neologism bit, which become metaphorically and technically imbricated in human discourse and the engineering projects they inform and describe. The term "bit," which was originally named an "alternative" by Shannon, was deemed at one point a "bigit," and, while, Tukey's memo may have been the first document we currently have access to in which the term appears, even a cursory reading of it reveals that drawing from it the conclusion that Tukey "coined" the term is far from certain (Tropp).

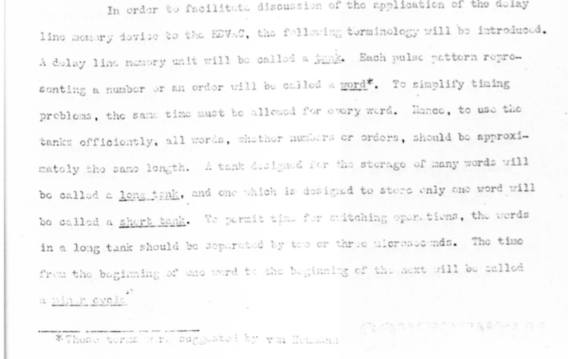

What's In a Word?: Teaching Machines to Read and Write

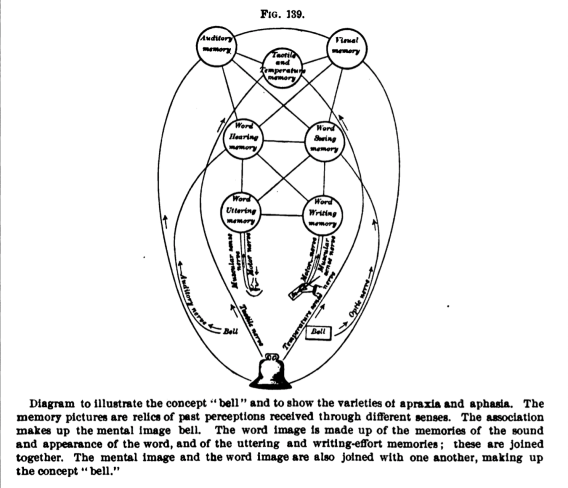

After 1946, the "signifying operations" (Rodgers) of terms related to and involving language as applied to digital electronic computers continue to widen in the technical, industrial, and popular literature (Nofre, Martin). Part of my interest in this relates to the fact that what we now call the early history of digital electronic computing, calculating machines are constructed based on models of the human, which are then explained via metaphors to influence decisions being made regarding the funding of educational and work initiatives for human computers and electronic computers based on the costs and interchangeability of the two (Grier). As Grace Hopper will point out in her 1952 article "The Education of a Computer," the EDVAC architecture is identical to a schematized cognitive model of a writing/calculating subject. In this context, the date and location of the drafting of the EDVAC Notes and later report are both significant considering their purpose and later reception, as are the later technical decisions that placed the affordances and performance standards of machinic operability over those of human legibility in the EDVAC project (Illustration 4). Yet, it is in part through verbal logic and the deployment of rhetoric that decisions were made regarding whose and what logics and languages would become "hard wired" into digital electronic computing machines.

Somewhat ironically, though, perhaps, inevitably, it is with issues of representation and the roles of spoken and inscribed language in depicting and constructing realities and histories that the intrigue involved with interpreting relationships between alphabetic words and computer words really begins. While it is impossible to know the exact reasons for a specific word choice, it is possible to consider the rhetorical contexts in which the EDVAC report was written. The term "word" functioned both to signal what was new about the project while also performing some explanatory work to an audience deciding the fate of the EDVAC funding proposals. Yet the target domain of this metaphor is human language processing, which it is presumed, rather than proved, that the proposed technical system will replicate (Harris). In giving the EDVAC calculating machine the ability to "instruct" itself with the metaphor of the word, binary arithmetic calculation is paired with alphabetic communication in a way that has implications for the processes involved with both and based on assumptions about how language functions, what the purposes of communication are, and for the benefit of specific parties and interests (Dick). From a writing studies perspective, the word choice of the "code word" and "word" connect the mid-1940s with the instrumentalization of writing and human writing subjects that had been occurring throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Gitelman, Rodgers) and to early discussions of "AI" and the roles and histories of writing, logic, and language education policies embedded in them (Kay, De Mol, Heyck).

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Joseph Tabbi, Cara Murray, and Robert Landon for their comments and suggestions related to earlier drafts of this article. Thank you also to Jeffrey Yost for his insightful suggestions, and to Amanda Wick and Melissa Dargay for their work and contributions. Holly Mengel, and David Azzolina for their assistance in remotely accessing a digital copy of "Automatic High Speed Computing: A Progress Report on the EDVAC," and to Donald Breckenridge for his practical, editorial, and emotional support. Finally, a special thanks to John H. Pollack, Curator, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries, and his colleagues Charles Cobine, Eric Dillalogue.

Bibliography

Alt, Franz. (July 1972). "Archaeology of Computers: Reminiscences, 1945-1947." Communications of the ACM, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 693–694. https://doi.org/10.1145/361454.361528.

Burks, Arthur W. (1978). "From ENIAC to the Stored-Program Computer: Two Revolutions in Computers." Logic of Computers Group, Technical Report No. 210. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/3961.

Burks, Arthur W., Herman H. Goldstine, and John von Neumann. (28 June 1946). Preliminary Discussion of the Logical Design of an Electronic Computer Instrument. Institute for Advanced Study. https://library.ias.edu/files/Prelim_Disc_Logical_Design.pdf

Campbell-Kelly, M. and Williams, M. R., eds. (1985). The Moore School Lectures: Theory and Techniques for Design of Electronic Digital Computers, volume 9 of Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series for the History of Computing. MIT P. https://archive.org/details/mooreschoollectu0000unse.

Ceruzzi, Paul E. (2021). "The Cloud, the Civil War, and the 'War on Coal.' Interfaces: Essays and Reviews in Computing and Culture, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. https://cse.umn.edu/cbi/interfaces.

De Mol, Liesbeth and Giuseppe Primiero. (2015). "When Logic Meets Engineering:

Introduction to Logical Issues in the History and Philosophy of Computer Science." History and Philosophy of Logic, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 195-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/01445340.2015.1084183.

Dick, Stephanie. (April–June 2013). "Machines Who Write." IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 88-87. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.2013.21.

Eckert, J. P. (1985). "A Preview of a Digital Computing Machine." The Moore School Lectures: Theory and Techniques for Design of Electronic Digital Computers, volume 9 of Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series for the History of Computing, edited by M. Campbell-Kelly and M.R. Williams, MIT P. https://archive.org/details/mooreschoollectu0000unsepp. 109-128.

Eckert, J. P. and Mauchly, J. W. (September 30, 1945). Automatic High Speed Computing: A Progress Report on the EDVAC, Moore School of Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania.

Gitelman, Lisa. (1999). Scripts, Grooves, and Writing Machines: Representing Technology in the Edison Era. Stanford UP.

Heyck, Hunter. (2014). “The Organizational Revolution and the Human Sciences.” Isis, vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 1–31. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/675549.

Harris, Roy. (1987). The Language Machine. Duckworth.

Haigh, Thomas, Mark Priestley, and Crispin Rope. (January-March 2014). "Reconsidering the Stored-Program Concept." IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 40-75. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.2013.56.

Haigh, Thomas and Mark Priestley. (January 2020). "Von Neumann Thought Turing's Universal Machine was 'Simple and Neat.': But That Didn't Tell Him How to Design a Computer." Communications of the ACM, vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 26-32. https://doi.org/10.1145/3372920.

Hopper, Grace M. “The Education of a Computer.” (1952). Proceedings of the 1952 ACM National Meeting (Pittsburgh), edited by ACM and C. V. L. Smith. ACM Press, pp. 243–49.

IEEE Standards Board. (1995). IEEE Standard Glossary of Computer Hardware Terminology. IEEE. doi: 10.1109/IEEESTD.1995.79522.

Kay, Lily. (2001). "From Logical Neurons to Poetic Embodiments of Mind: Warren S. McCulloch's Project in Neuroscience." Science in Context vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 591-614.

Martin, C. Dianne. (April 1994). "The Myth of the Awesome Thinking Machine." Communications of the ACM, vol. 36, no.4, pp: 120-33.

Nofre, David, Mark Priestley, and Gerard Alberts. (2014). "When Technology Became Language: The Origins of the Linguistic Conception of Computer Programming, 1950–1960." Technology and Culture, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 40-75.

Priestley, Mark. (2018). Routines of Substitution: John von Neumann’s Work on Software Development, 1945–1948. Springer.

Report to Conference on Data Systems and Languages Including Initial Specifications for a Common Business Oriented Language (COBOL) for Programming Electronic Digital Computers. (April 1960). Department of Defense.

Rodgers, Johannah. (July 2020). "Before the Byte, There Was the Word: Exploring the Provenance and Import of the 'Computer Word' for Humans, for Digital Computers, and for Their Relations." (Un)-Continuity: Electronic Literature Organization Conference, 16-18 July 2020, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/ elo2020/asynchronous/talks/11/.

Starr, M. Allen. (1895). "Focal Diseases of the Brain." A Textbook of Nervous Diseases by American Authors edited by Francis X. Dercum, Lea Brothers. https://archive.org/details/b21271161

Stibitz, George R. (1948). “The Organization of Large-Scale Computing Machinery.”

Proceedings of a Symposium on Large-Scale Digital Calculating Machinery, Harvard UP, pp. 91–100.

Tropp, Henry S. "Origin of the Term Bit." (April 1984). Annals of the History of Computing, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 154-55. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/357447.357455.

von Neumann, J. (June 30, 1945). First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC. Moore School of Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania. https://history-computer.com/Library/edvac.pdf.

von Neumann, J. (1993). "First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC." IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 15, No. 04, pp. 27-75. doi: 10.1109/85.238389.

Williams, Michael R. (1993). "The Origins, Uses, and Fate of the EDVAC." IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 22-38.

Johannah Rodgers (September 2021). “Before the Byte, There Was the Word: The Computer Word and Its Many Histories.” Interfaces: Essays and Reviews on Computing and Culture Vol. 2, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, 76-86.

About the author:

Johannah Rodgers is a writer, artist, and educator whose work engages creatively and critically with the histories and presents of print and digital technologies to explore their connections and their roles in the sociologies and economics of literacies in the U.S. She is the author of Technology: A Reader for Writers (Oxford University Press, 2014), the Founding Director of the First Year Writing Program at the New York City College of Technology, where she was Associate Professor, and a participant in the 2020-21 University of Cambridge Mellon Sawyer Seminar on the Histories of AI. You can read more about her projects and publications at www.johannahrodgers.net.

Early “Frictions” in the Transition towards Cashless Payments

Bernardo Bátiz-Lazo (Northumbria) and Tom R. Buckley (Sheffield)

Abstract: In this article we describe the trials and tribulations in the early stages to introduce cashless retail payments in the USA. We compare efforts by financial service firms and retailers. We then document the ephemeral life of one of these innovations, colloquially known as “Hinky Dinky”. We conclude with a brief reflection on the lessons these historical developments offer to the future of digital payments.

Photo credit: “Supermarkets as S&L Branches,” Banking Vol. 66 (April 1974) pg. 32

Let’s go back to the last quarter of the 20th century. This was a time when high economic growth in the USA that followed the end of World War II was coming to an end, replaced by economic crisis and high inflation. It was a time where cash was king, and close to 23% of Americans worked in manufacturing. A time when the suburbs – to which Americans had increasingly flocked after 1945 escaping city centres – were starting to change. Opportunities for greater mobility were offered by automobiles, commercial airlines, buses, and the extant railway infrastructure.

This was the period that witnessed the dawn of the digital era in the United States, as information and communication technologies began to emerge and grow. The potential of digitalisation provided the context in which an evocative idea, the idea of a cashless society first began to emerge. This idea was associated primarily with the elimination of paper forms of payment (primarily personal checks) and the adoption of computer technology in banking during the mid-1950s (Bátiz-Lazo et al., 2014). Here it is worth noting that, although there is some disagreement as to the exact figure, the volume of paper checks cleared within the U.S. had at least doubled between 1939 and 1955, and the expectation was, that this would continue to rise. This spectacular rise in check volume, with no corresponding increase in the value of deposits, placed a severe strain on the U.S. banking system and lead to a number of industry-specific innovations emerging from the 1950s such as the so-called ERMA and electronic ink characters (Bátiz-Lazo and Wood, 2002).

The concept of the cashless, checkless society became popularised in the press on both sides of the Atlantic in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Very soon the idea grew to include paper money. At the core of this imagined state was the digitalization of payments at the point of sale, a payment method that involved both competition and co-operation between retailers and banks (Maixé-Altés, 2020 and 2021).

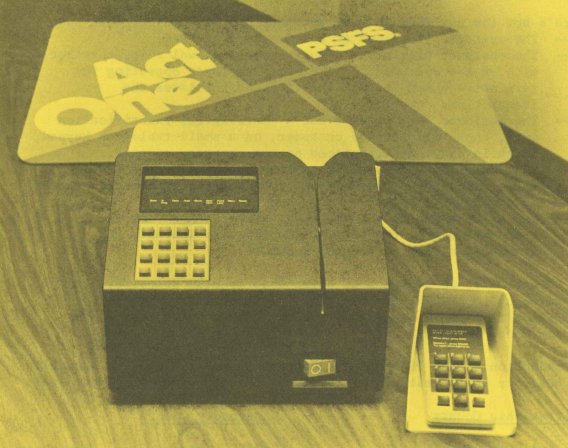

Photo credit: Hagley Museum and Archives Philadelphia Savings Fund Society Collection 2062 Box 13 PSFS Online News Bulleting, Vo 80-102, June 23 1980.

In the banking and financial industry new, transformative technologies thus began to be trialled and developed in order to make this a reality (Maixé-Altés, 2019). Financial institutions accepting retail deposits had been at the forefront of the adoption of commercial applications of computer technology (Bátiz-Lazo et al., 2011). Early forms of such technical devices mainly focused on improving “back office” operations and encompassed punch card electromechanical tabulators in the 1920s and 1930s; later, in the 1950s, analogue devices (such as the NCR Post Tronic of 1962) were introduced, and, in the late 1960s the IBM 360 became widely adopted. But at the same time, regulation curtailed diversification of products and geography (limiting the service banks could provide their customers). These regulatory restrictions help to explain ongoing experiments with a number of devices which involved a significant degree of consumer interaction including credit cards (Stearns, 2011), the use of pneumatic tubes and CCTV in drive through lanes, home banking, and Automated Teller Machines (ATMs), which despite being first introduced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, would ultimately not gain acceptance until the early 1980s (Bátiz-Lazo, 2018).

Like the banking and financial industry, the retail industry, with its very real interest in point of sale digitalization, was exposed to the rise of digital technology in the last quarter of the 20th Century. The digitalisation of retailing occurred later than in other industries in the American economy (for a European account see Maixé-Altés and Castro Balguer, 2015). Once it arrived, however, the adoption of a range of digital technologies including Point of Sale (POS) related innovations such as optical scanning, and the universal product code (UPC), were extensive and transformed the industry (Cortada, 2003). From the perspective of historical investigation, the chronological place of such innovation, beginning in the mid-1970s, is associated with a remarkable period of rapid technological change in U.S. retailing (Basker, 2012; Bucklin 1980). Along with rapid technological change, shifts in the structure of retail markets, in particular the decline of single “mom and pop stores” and the ascent of retail chains also became more pronounced in the 1970s (Jarmin, Klimek and Miranda, 2009). Two decades later, such large, retail firms would account for more than 50% of the total investment in all information technology by U.S. retailers (Doms, Jarmin and Kilmek, 2004).

What connects the transformative technological changes that occurred in both the banking industry and the retail industry during this period, is that both sought to utilise Electronic Funds Transfer Systems, or EFTS, a way to reduce frictions for retail payments at the point of sale. During the 1970s and 1980s, the term EFTS was used in a number of ways. Somewhat confusingly, it was applied indistinctively to specific devices or ensembles, value exchange networks, and what today we denominate as infrastructures and platforms. While referring to it as a systems technology for payments it was defined as one:

“in which the processing and communications necessary to effect economic exchange and the processing and communications necessary for the production and distribution of services incidental to economic exchange are dependent wholly or in large part on the use of electronics” (National Commission on Electronic Funds Transfer, 1977, 1).

Ultimately EFTS would come to be extended to the point of sale and embodied in terminals which allowed for automatic, digital, seamless transfer of money from the buyer’s current account to the retailer’s, known as the Electronic Funds Transfer at the Point of Sale, or EFTS-POS (Dictionary of Business and Management: 2016).

One of the factors that initially held back the adoption of early EFTS and the equipment that utilities it, was the lack of infrastructure that would connect the user, the retailer, and the bank (or wherever the user’s funds were stored). As Bátiz-Lazo et al. (2014) note the idea of a cashless economy that would provide this infrastructure was highly appealing… but implementing its actual configuration was highly problematic. Indeed, in contrast to developments in Europe, some lawmakers in Congress considered the idea of sharing infrastructure by banks as a competitive anathema (Sprague, 1977). Large retailers such as Sears had a national presence and were able to consider implementing their own solution to the infrastructure problem. Small banks looked at proposals by the likes of Citibank with scepticism while they feared it may pivot the dominance of large banks. George W. Mitchell (1904-1997), a member of the Board of the Federal Reserve, and management consultant John Diebold (1926-2005), were outspoken promoters of the adoption of cashless solutions but their lobbying of public and private spheres was not always successful. Perhaps the biggest chasm between banks and retailers though, resulted from the capital-intensive nature of the potential network and infrastructure that any form of EFTS required.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Diebold-Wincor Inc.

Amongst the alternative solutions that were trialled by banks and retailers, there were a number of successes, such as ATMs (Bátiz-Lazo, 2018) and credit cards (Ritzer, 2001; Stearns, 2011). Both bankers and retailers were quick to see a potential connection between the machine-readable cards and the rapid spread of new bank-issued credit cards under the new Interbank Association (i.e., the genesis of Mastercard) and the Bankamericard licensing system (i.e., the genesis of Visa), both of which began in 1966, just as the vision of the cashless society was winning acceptance. Surveys from the time indicate that at least 70 percent of bankers believed that credit cards were the first step toward the cashless society and that they were entering that business in order to be prepared for what they saw as an inevitable future (Bátiz-Lazo et al., 2014).

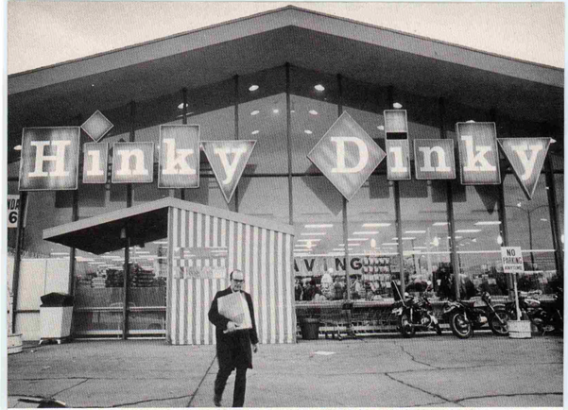

There were also a number of less successful attempts that, far from being relegated to the ignominy of the business archives, offer an important insight into the implementation of a cashless economy which is worth preserving for future generations of managers and scholars. Chief amongst these is a system widely deployed by the alliance of U.S. savings and loans (S&L) with mid-sized retailers under the sobriquet “Hinky Dinky”. Interestingly, Maixé-Altés (2012, 213-214) offers an account of a similar, independent, and contemporary experiment in, a very different context, Spain. The Hinky Dinky moniker was derived from an experiment by the Nebraskan First Federal Savings and Loan Association, which in 1974 located computer terminals into stores of the Hinky Dinky grocery chain - which at its apex operated some 50 stores across Iowa and Nebraska. The Hinky Dinky chain was seen by the First Federal Savings and Loan Association as the perfect retail partner for this experiment owing to the supermarket’s popularity with local customers; an appeal that would be beneficial to this new technology. The popularity of Hinky Dinky was particularly valuable, as the move by First Federal Savings and Loans, to establish an offsite transfer system challenged, but did not break banking law at that time (Ritzer, 1984).

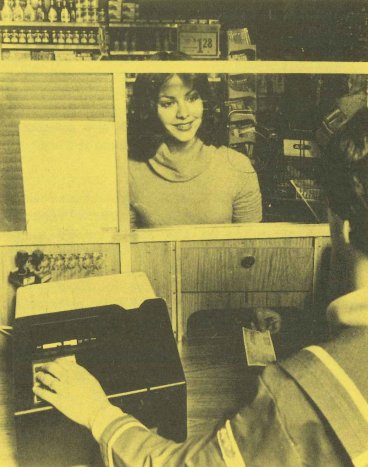

At the heart of the technical EFT system initiated by First Federal, formally known as Transmatic Money Service, was a rudimentary, easy-to-install package featuring a point-of- service machine, with limited accessory equipment in the form of a keypad and magnetic character reader. The terminal housed in a dedicated booth within the store and was operated by store employees (making a further point of the separation between bank and retailer). The terminal enabled the verification and recording of transactions as well as the instant updating of accounts. The deployment of the terminals in Hinky Dinky stores shocked the financial industry because it made the Nebraska S&L appear to be engaging in banking activities, while the terminals themselves provided banking services to customers in a location that was not a licensed bank branch!

Photo credit: Hagley Museum and Archives Philadelphia Savings Fund Society Collection 2062 Box 13 PSFS Online News Bulleting, Vo 79-127, September 13, 1979.

From its origins in a mid-sized retail chain in the Midwest, some 160 “Hinky Dinky” networks appeared across the USA between 1974 and 1982, before S&Ls abandoned them in favour of ATMs and credit cards. These deployments included a roll out in 1980 by the largest savings banks by assets in the USA at the time, the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society or the PSFS. Rather than commit to the large capital investment that ATMs necessitated, without guarantees of its viability or a secure return on investment, the PSFS pivoted the “Hinky Dinky” terminals as part of the rolled out of its negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts (commercialised as “Act One”).

The NOW accounts were launched in the early 1970s by the Consumer Savings Bank, based in Worcester, MA (today part of USBank), as way to circumvent the ban on interest payment and current account deposits imposed on S&Ls by Depression era regulation. Between 1974 and 1980, Congress took incremental steps to allow NOW accounts nationwide, something the PSFS wanted to take advantage of. Consequently, in February 1979, the PSFS signed an agreement with the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P) to install Transmatic Money Service devices in 12 supermarket locations. This was part of the PSFS wider strategy “to provide alternative means for delivering banking services to the public” (Hagley Archives: PSFS Collection).

These terminals did not, however, allow for the direct transfer of funds from the customer’s accounts to the retailers. Rather the terminals, which were operated by A&P employees, were activated by a PSFS plastic card that the society issued to customers, and enabled PSFS customers with a Payment and Savings account to make withdrawals and deposits. The terminals also allowed PSFS cardholders and A&P customers to cash cheques.

The equipment used by PSFS, the Hinky Dinky devices, therefore represent an interesting middle ground which improved transaction convenience for consumers, was low risk for the retailer and was relatively less costly for banks and financial institutions than ATMs (Benaroch & Kauffman, 2000).

One of the most interesting features of the Hinky Dinky terminals as they were deployed by the PSFS and First Federal Savings, was that they represent co-operative initiatives between retail organisations and financial institutions. As mentioned before, this was not necessarily the norm at the time. As the legal counsel to the National Retail Merchants Association (a voluntary non-profit trade association representing department, speciality and variety chain stores) wrote in 1972: “Major retailers… have not been EFTS laggards. However, their efforts have not necessarily or even particularly been channelled toward co-operative ventures with banks,” (Schuman, 1976, 828). These sentiments were echoed by more neutral commentators who similarly highlighted the lack of dialogue between retailers and financial institutions on the topic of EFTS (Sprague, 1974). The extent to which retailers provided financial services to their customers had long been a competitive issue in the retail industry: the ability of chain stores, such as A&P in groceries and F.W. Woolworth in general merchandise, to offer low prices and better value owed much to their elimination of credit and deliveries (Lebhar, 1952). With the advent of EFT retail organisation’s provision of financial services raised the prospect of this becoming a competitive issue between these two industries.

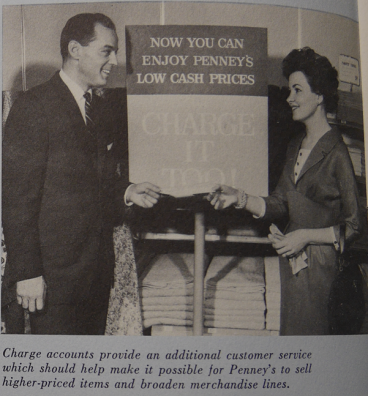

Photo credit: From J.C Penney 1959 Annual Report.

The prospect of a clash between retailers and banks was increased moreover, as there had always been other voices, other retailers, who had been willing to offer credit (Calder, 1999). In the early years of the 20th century, consumer demand for retailers to provide credit grew. This caused tension with the cash only policies of department store such as A.T. Stewart and Macy’s, and the mail order firms Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward (Howard, 2015). Nevertheless, it was hard to ignore such demand as evidenced by Sears decision to begin selling goods on instalment around 1911 (Emmet and Jeuck, 1950, 265). Twenty years later, in 1931, the company went a stage further by offering insurance products to consumers through the All State Insurance Company. Other large retail institutions, however, resisted the pressure to offer credit until much later (J.C. Penney for instance would not introduce credit until 1958). Credit activities by large retailers, nonetheless, were determinant for banks to explore their own credit cards as early as the 1940s while leading to the successes of Bankamericacard and the Interbank Association in the 1960s (Bátiz-Lazo and del Angel, 2018; Wolters, 2000).

The barriers between banks and financial institutions on the one hand, and retailers on the other, continued to remain fairly robust. Signs that this was beginning to change began to emerge in the 1980s, when retailers, such as Sears began to offer more complex financial products (Christiansen, 1987; Ghemawat, 1984; Raff and Temin, 1997). Yet, the more concerted activity by retailers to diversify into financial services, would ultimately be stimulated by food retailers (Martinelli and Sparks, 1999; Colgate and Alexander, 2002). The Hinky Dinky System however shows that a co-operative not just a competitive solution was a very real possibility.

In 2021 we are witnessing an extreme extension and intensification of these trends. Throughout the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the use of cash has greatly declined as more and more people switch to digital payments. In the retail industry, even before the pandemic, POS innovations were becoming increasingly digital (Reinartz and Imschloβ, 2017) as retailers shifted toward a concierge model of helping customers rather than simply focusing on processing transactions and delivering products (Brynjolfsson et al., 2013). Consequently, the retail-customer interface was already starting to shift away from one that prioritised the minimisation of transaction and information costs toward an interface which prioritised customer engagement and experience (Reinartz et al., 2019).

A second feature of the pandemic has been the massive increase in interest in crypto currencies, in its many different forms, around the world. This is most apparent in the volatility and fluctuations in price of Bitcoin but is also evident in the increased prominence of alternative fiat currencies (such as Ether). Indeed, even central banks in Europe and North America are discussing digital currencies, the government of El Salvador has made Bitcoin legal tender, while the People’s Bank of China have launched their own digital currency in China. A further manifestation of the momentum crypto currencies are gaining include the private initiatives of big tech (such as Facebook’s Diem, formerly Libra). Yet, in spite of all of this latent promise, transactions at point of sale with crypto currencies are still minuscule and time and again, surveys by central banks on payment preferences consistently report people want paper money to continue to play its historic role.

It thus remains too early to forecast with any degree of certainty what the actual long-run effects of the virus, social distancing and lockdowns will have on the use of cash, how consumers acquire products and services, and what these products and services are. It is also uncertain whether and if greater use of crypto currencies will lead to a decentralised management of monetary policy (and if so, the rate at which this will take place). It is though almost certain that consumer’s behaviours, expectations and habits will have been altered by their personal experiences of Covid. In this context the story behind “Hinky Dinky” reminds us to be sober at a time of environmental turbulence and wary of extrapolating trends, to better understand the motivation driving the adoption of new payment technology as some of these trends, like “Hinky Dinky”, might look to have wide acceptance but to result in a short-term phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate helpful comments from Jeffrey Yost, Amanda Wick and J. Carles Maixé-Altés. As per usual, all shortcomings remain responsibilities of the authors.

Bibliography

Basker, E. (2012). Raising the Barcode Scanner: Technology and Productivity in the Retail Sector. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(3), 1-27.

Bátiz-Lazo, B. (2018). Cash and Dash: How ATMs and Computers Changed Banking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bátiz-Lazo, B., Maixé-Altés, J. C., & Thomes, P. (2011). Technological Innovation in Retail Finance: International Historical Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge.

Bátiz-Lazo, B., Haigh, T., & Stearns, D. L. (2014). How the Future Shaped the Past: The Case of the Cashless Society. Enterprise & Society, 15(1), 103-131.

Bátiz-Lazo, B., & del Ángel, G. (2018). The Ascent of Plastic Money: International Adoption of the Bank Credit Card, 1950-1975. Business History Review, 92(3 (Autumn)), 509 - 533.

Bátiz-Lazo, B., & Wood, D. (2002). An Historical Appraisal of Information Technology in Commercial Banking. Electronic Markets - The International Journal of Electronic Commerce & Business Media, 12(3), 192-205.

Benaroch, M., & Kauffman, R. J. (2000). Justifying Electronic Banking Network Expansion Using Real Options Analysis. MIS quarterly, 197-225

Bucklin, L. P. (1980). Technological-change and Store Operations-The Supermarket Case. Journal of retailing, 56(1), 3-15.

Calder, L. (1999). Financing the American Dream: A Cultural History of Consumer Credit. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Colgate, M., & Alexander, N. (2002). Benefits and Barriers of Product Augmentation: Retailers and Financial Services. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(1-2), 105-123.

Cortada, J. (2004). The Digital Hand, Vol 1: How Computers Changed the Work of American Manufacturing, Transportation, and Retail Industries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chrstiansen, E. T. (1987) Sears, Roebuck & Company and the Retail Financial Services Industry (Part Two). Case 9-387-182. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School.

Doms, M. E., Jarmin, R. S., & Klimek, S. D. (2004). Information technology Investment and Firm Performance in US Retail Trade. Economics of Innovation and new Technology, 13(7), 595-613.

Emmet, B., Jeuck, J. E., & Rosenwald, E. G. (1950). Catalogues and Counters: A History of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ghemawat, P. (1984) Retail Financial Services Industry, 1984. Case 9-384-246, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School.

Hagley Museum and Archives Philadelphia Savings Fund Society Collection 2062 Box 13 POS Program Introduction March 2, 1978.

Howard, V. (2015). From Main Street to Mall: The Rise and Fall of the American Department Store. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Jarmin, R. S., Klimek, S. D., & Miranda, J. (2009). The Role of Retail Chains: National, Regional and Industry results. In Producer dynamics: New evidence from micro data (pp. 237-262). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lebhar, G. M. (1952). Chain stores in America, 1859-1950. New York: Chain Store Publishing Corporation.

Martinelli, E. and Sparks, L. (2003). Food Retailers and Financial Services in the UK: A Co‐opetitive Perspective", British Food Journal, Vol. 105 No. 9, pp. 577-590.

Maixé-Altés, J. C. (2012). Innovación y compromiso social. 60 años de informatización y crecimiento. Barcelona: "la Caixa" Group.

Maixé-Altés, J. C. (2019): "The Digitalisation of Banking: A New Perspective from the European Savings Banks Industry before the Internet," Enterprise and Society, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 159-198.

Maixé-Altés, J. C. (2020): "Retail Trade and Payment Innovations in the Digital Era: A Cross-Industry and Multi-Country Approach", Business History Vol. 62, No. 9, pp. 588-612.

Maixé-Altés, J. C. (2021): "Reliability and Security at the Dawn of Electronic Bank Transfers in the 1970s-1980s". Revista de Historia Industrial, Vol. 81, pp. 149-185.

Maixé-Altés, J. C. and Castro Balguer, R. (2015): "Structural Change in Peripheral European Markets. Spanish Grocery Retailing, 1950-2007", Journal of Macromarketing, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 448-465.

Raff, D., & Temin, P. (1999). Sears, Roebuck in the Twentieth Century: Competition, Complementarities, and the Problem of Wasting Assets. In Learning by doing in markets, firms, and countries (pp. 219-252). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reinartz, W., & Imschloβ, M. (2017). From Point of Sale to Point of Need: How Digital Technology is Transforming Retailing. NIM Marketing Intelligence Review, 9(1), 42.

Reinartz, W., Wiegand, N., & Imschloβ, M. (2019). The Impact of Digital Transformation on the Retailing Value Chain. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(3), 350-366.

Ritzer, G. (2001). Explorations in the Sociology of Consumption: Fast Food, Credit Cards and Casinos. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

Ritzer, J. (1984) Hinky Dinky Helped Spearhead POS, remote banking movement. Bank Systems and Equipment, December, 51-54.

Schuman, C. R. (1975). The Retail Merchants' Perspective Towards EFTS. Catholic University Law Review, 25(4), 823-842.

Sprague, R. E. (1977). Electronic Funds Transfer In Europe: Their Relevance for the United States. Savings Banks International, 3, 29-35.

Sprague, R.E. (1974) Electronic Funds Transfer System. The Status in Mid-1974 – Part 2. Computers and People 23(4).

Stearns, D. L. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer-Verlag.

United States. National Commission on Electronic Funds Transfer. (1977). EFT and the public interest: a report of the National Commission on Electronic Fund Transfers. Second printing. Washington: National Commission on Electronic Fund Transfers.

Wolters, T. (2000). ‘Carry Your Credit in Your Pocket’: The Early History of the Credit Card at Bank of America and Chase Manhattan. Enterprise & Society, 1(2), 315-354.

Bátiz-Lazo, Bernardo and Buckley, Tom R. August (2021). “Early “Frictions” in the Transition towards Cashless Payments.” Interfaces: Essays and Reviews in Computing and Culture Vol. 2, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, 64-75.

About the authors:

Dr. Bernardo Bátiz Lazo is Professor of FinTech History and Global Trade at Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK and research professor at Universidad Anahuac (Mexico). He is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society and the Academy of Social Sciences.

Dr. Tom Buckley is currently Lecturer in International Business Strategy at the University of Sheffield. Dr. Buckley received his PhD from the University of Reading’s Henley Business School in 2017.

Top 10 Signs We Are Talking About IBM’s Corporate Culture

James W. Cortada, Senior Research Fellow, Charles Babbage Institute

Abstract: Using the format of a late night TV humorist's way of discussing an issue, this article defines ten characteristics of IBM's corporate culture deemed core to the way IBM functioned in the twentieth century. The perspective is of the individual employee's behavior, conjuring up with humorous images what they thought of each other's behavior. However, corporate images are serious matters so as historians focus more attention on corporate cultures, such images will need to be understood. The list also demonstrates that one image of IBM personnel as being serious did not always reflect reality within the company.

Between 1982 and 2015, comedian and American television host David M. Letterman hosted a highly popular late-night television comedy show, Late Night with David Letterman. One of his recurring presentations was the “Top 10 List,” which ranked from tenth to first features of an issue. These became wildly popular, were satirized, and taken to be comedic commentary on contemporary circumstances. He and his staff produced nearly 700 such lists, while Letterman hosted over 6,000 programs viewed by millions of people. He published four book-length collections of these lists. The genius of these lists, as in any good comedy, lay in providing a slightly fractured view of reality. On occasion, he commented on corporations, such as GE, AT&T, Exxon, McDonalds, QVC and Westinghouse among others.

In recent years scholars have become increasingly interested in the history of corporate cultures. For decades historians said corporate cultures were important, but they did little work on the subject. That is beginning to change. I am exploring IBM’s corporate culture, which historians and employee memoirists all claim was central to the company’s ability to thrive and survive longer than any other firm in the IT industry. So, to do that historians have to find new types of documentation informing their study of the subject. That is why we are turning to comedian David Letterman. His lists reflected public interest in a topic, and they captured perspectives people would either agree with or that made sense to them given what they knew of the subject. What better way is there to see what IBM’s image looked like: “10 Signs you might be Working at IBM”:

“10. You lecture the neighborhood kids selling lemonade on ways to improve their process.”

Thomas J. Watson Sr., head of IBM from 1914 to 1956, made exploring with customers how best to use his tabulators, then computers, a central feature of his selling method. Tens of thousands of sales personnel did this. In the process they and other employees improved IBM’s operations and were seen as experts on efficient, productive business operations. As the company grew in size, so too did its reputation for having “its act together” on all manner of business and technical issues. That reputation expanded, crowned with the acquisition of 30,000 management and IT consultants from PwC in 2002. There was no industry or large company immune from IBM’s views on how to improve operations, nor community organization involving IBMers. (Side note: Your author—retired IBMer—taught his daughters how to improve their Girl Scout cookie sales process.)

“9. You get all excited when it’s Saturday so you can wear shorts to work.”

The two things most people know about IBM in any decade is its THINK sign and that its employees always wore dark suits, white shirts, regimental ties, black socks and shoes. It turns out, they did that, not because someone at the top of the corporation mandated such a dress code, rather because that is how customers tended to dress. There was no official dress code, although most IBMers can tell a story of some lower level manager sending someone home to change out of their blue shirt or, shockingly out of their brown loafers. But Thomas J. Watson, Jr., CEO between 1956 and 1971 finally opined in the subject in 1971, confessing that IBM’s customers dressed in a “conservative” manner. He thought, “it is safe to say that the midstream of executive appearance is generally far behind the leading edge of fashion change.” So, “a salesman who dresses in a similar conservative style will offer little distraction from the main points of business discussion and will be more in tune with the thinking of the executive.” That is why, “we have always had a custom of conservative appearance in IBM.” People are thus asked, “to come to work appropriately dressed for their job environment.” That’s it: the smoking gun, the root source of the true IBM dress code policy! Millions of people have met IBM employees wearing blue suits. Sociologists point out that every profession has its uniform (e.g., university students blue jeans, cooks their tall white hats, IBMers their wingtips and white shirts). The Letterman quip inferred below is that IBM employees were willing to put in long hours on behalf of their company.

“8. You refer to the tomatoes grown in your garden as deliverables.”

Deliverables is a word with a long history at IBM, at least back to the 1950s. While its exact origins are yet to be uncovered, technical writers worked with product developers on a suite of publications that needed to accompany all product announcements or modifications to them. In fact, one could not complete a product development plan without including as one of its deliverables a communication plan in writing. The plan had to include when and how press releases, General Information and user and maintenance manuals would be published, and how these would accompany products to customers’ data centers. When IBM entered the services business focusing largely on doing management and strategy consulting in the 1990s with the creation of the IBM Consulting Group use of the word expanded across IBM. Management consultants in such firms as Ernest & Young, Booze Allen and McKinsey, among others, always concluded their consulting projects with a final report on findings and recommendations, which they, too, called deliverables. So as these people came to work at IBM, they brought with them their language. By the end of the 1990s, it seemed everyone was using deliverables to explain their work products. So, the Letterman List got right another IBM cultural trait that proved so pervasive that even employees did not realize they said deliverables.

“7. You find you really need Freelance to explain what you do for a living.”

Oh, this one hurts if you are an IBMer. The “Ouch” is caused by the fact that during the second half of the twentieth century, employees attended meetings armed with carefully prepared slide presentations. They began with Kodak film slides, then 8 x 10 film called foils (IBMers may have had an exclusive in using that word), followed by the precursor of PowerPoint called Freelance. Every manager it seemed carried a short presentation about their organization, what it did and so forth. By the end of the 1960s it seemed no proposal to a customer or higher-level manager was missing the obligatory presentation. When Louis V. Gerstner came to IBM as its new CEO in 1993, he immediately noticed this behavior and essentially outlawed the practice by his executives when meeting with him. He wanted them to look into his eyes and talk about “their business.” Eventually he retired and so by the early 2000s, PowerPoint was back. By the 2010s the nearly two hundred firms acquired by IBM came fully stocked with employees who, too, clutched their slide presentations. Edward Tufte, the Yale professor who is most noted for his multi-decade criticism of PowerPoint presentations, must clearly have had IBM in mind, although he admitted many corporations suffered from similar behavior. He went on to study the role of graphics and presentation of statistics and other data.

“6. You normally eat out of vending machines and at the most expensive restaurant in town within the same week.”

This observation required true insight. One of the TV writers must have interviewed a salesman, consultant, any manager or executive to stumble across this one. IBM people spent a considerable amount of time traveling to visit customers, attend internal and industry meetings, fulfill their normal requirement of two weeks of training every year, attend conferences to make presentations, or to meet with government officials. By the 1980s it was not uncommon for large swaths of IBM to be organized in some matrix manner in which one’s immediate supervisor was in another country while yet another manager with whom one had to work with was perched elsewhere. To kiss the ring, one had to travel to wherever that manager held court. Some professions, such as sales and consulting and middle and senior management, turned themselves into tens of thousands of “road warriors.” So, one might fly to a city and take a customer out to dinner at a magnificent restaurant to build personal rapport and to conduct business, in slang terms sometimes referred to as “tavern marketing.” But then afterwards rushed to the airport to catch the “red eye” overnight flight home or to some other destination to attend yet another meeting. That would require possibly eating vending machine food after an airport’s restaurants closed, at a work location that had no restaurant or when there was no time to rush out for something. IBMers, too, prided themselves in making their flights “just in time,” meaning no time for having a leisurely meal. You were complimented if you reached the airplane’s door just as it was about to be closed.

“5. You think that “progressing an action plan” and “calenderizing a project” are acceptable English phrases.”

Since at least the 1970s, employees putting together those famous slide presentations were retreating from writing full sentences, engaged in the very bad habit of turning nouns into verbs. Technical writers in the firm eschewed such behavior, so too the media relations community. Employees working in headquarter jobs in the United States, were particularly notorious users of nouns. Letterman may not have known of the most widely used example, “to solution” something or its variant “I will solution that problem.” The use of a noun was intended to project force, action, determination, and leadership. Nobody seemed embarrassed by their ignorance of the English language. If one worked in the same building as hundreds or thousands of people without visiting too many other workplaces, local speech patterns became evident. The New York area’s IBM community was notorious; they wanted people to come to them and when that happened visitors were abused with such language. As cultural anthropologists pointed out since Claude Levi-Strauss as early as the 1930s, tribes form their own language tied to their cultures and lifestyles. IBMers were guilty of the same. It is part of the behavior that led to such usages as “foils.”

“4. You know the people at faraway hotels better than your next-door neighbors.”

This has to qualify as true for some road warriors. It ties to No. 6 about vending machines. Consultants, in particular, would leave home on a Sunday night or Monday morning and not return until Friday night, if on long term projects. They were commuting and so when home, took care of domestic chores or spent time with their families. It was—is—not uncommon for employees to know the names of flight attendants and hotel staff, since those individuals, too, had set work schedules. Knowing the name of restaurant staff working near a client’s offices was—is—not uncommon, either. Such knowledge could be exotic, as knowing the flight attendant assigned to one’s Monday morning flight to Orange County, California, and at the same time the doorman at one’s favorite Lebanese restaurant in Paris. This is not conceit, just the reality that IBM employees did a considerable amount of traveling in the course of their career. It was both an attraction and a burden. Travel made work interesting but also placed a burden on one’s Circadian body rhythms not helped by rich food or vending machine delights.

“3. You ask your friends to “think outside the box” when making Friday night plans.”

In IBM’s culture solving problems is a practice shared by all employees almost all the time. It became a worldview, a framework, and an attitude toward activities in both their professional and private lives. It has been fostered within the firm since the 1910s, largely because the products it sold required addressing customer issues and others challenging the internal operations at IBM. Over the years, language and phrases emerged that were embraced to speak to that issue. Thinking outside the box spoke to the need often required to come up with a solution to a problem that had not been tried before. That behavior prized imagination and equally so, a reluctance to accept no as an answer to a request. For a century, for example, salesmen and engineers were taught when encountering an objection or a problem not to take it personally, but to decompose it to understand what it really is, and then come up with a “fix” for it. There was an age-old sales adage that helps here: “The selling doesn’t start until the customer says no.” Flipping a “no” into a “yes” requires “thinking outside the box.” The same mindset was applied in one’s private life too.

“2. You think Einstein would have been more effective had he put his ideas into a matrix.”

Someone must have had spies in IBM or was a business school professor of organizational theory, because by the 1960s, much of IBM was organized like a matrix. As one student of IBM’s culture with experience studying corporate structures explained: “I’ve never seen this in any other company,” adding, “with all those dotted lines and multiple bosses.” However, it worked because everyone subscribed to a common set of values and behaviors, and all had documented performance plans that stated explicitly what they were to do. Where one sat in IBM insured that in everyone’s slide presentations there would be an organization chart to which the speaker could point out to explain where they perched. Another observer opined that, “It is probably the most complex organization that I have seen,” enter the illusion to smart Albert Einstein. Hundreds of thousands of employees lived in such matrices and somehow it all worked, because IBM made money and profits, with a few exceptions that Letterman and his audience might not even have been aware of, since most stockholders were the rich and institutional investors.

Following Letterman’s practice: “And the Number One Sign That You Work at IBM” with a drum roll, of course:

“1. … You think a ‘half-day’ means leaving at 5 o’clock.”

Employees had a work ethic that customers saw displayed in many ways: travel schedules, customer engineers working around the clock and over weekends to install and repair hardware and software, consultants who showed up at 8 in the morning and left at 7:30 to dine at one of those fine restaurants or to wolf down pizzas as they prepared for a client presentation to be made first thing in the morning. It was a life of endless dinners with clients and one’s management, or student teams working on case studies until midnight in some training program. Weekend planning retreats were all too common, especially in the fall as IBMers prepared for next year, or for spring reviews which were a ritual requiring weeks of preparation for when executive management would swoop in to inspect, often knowing as much about one’s business as the presenters. The company did nothing to hide the long hours its employees put in—it exemplified the wisdom of the Grand Bargain. This bargain held that in exchange for working loyally and to a great extent, one was assured a lifetime of employment at IBM. The 5 o’clock comment recognized that employees were seen as far more loyal to the firm and defender of its ways than evident in other companies. One sees such comments in bits and pieces in memoirs and accounts of the IT industry, but the Letterman list cleverly summed it up.

So, what was the image the Letterman List portrayed of IBMers to millions of people? While many had a good laugh, it affirmed that IBM’s employees were serious, knowledgeable, seemingly always on duty (even at home and in their neighborhood), focused on results, were imaginative, and had their own ways of doing and talking. IBM had purposefully worked on developing that image since the 1910s and a century later still retained it. It was part of a larger, hardly discussed, corporate strategy of creating an information/business ecosystem in the world of IT which it dominated.

But, of course, what Letterman may have missed are so many other lists, such as those hundreds of line items defining IBM (e.g., I’ve Been Moved). IBMers did not sleep wearing their black wingtip shoes, nor cut their lawns wearing white shirts. They actually had a sense of humor as historians are beginning to discover. IBMers conjured up comedic skits across the entire company around the world. They did standup joke telling, and, of course, sang songs, often with lyrics tailored to some Letterman-like observations about IBM.

But here is the punch line. Letterman never drew up this list, it is a spoof, prepared by an IBMer that circulated around the Internet. It was probably written in 1997, while IBM’s old culture was still much in place, when what was said here were IBM employee insights into the company’s culture. In short, there is more accuracy in this list than the comedian could have conjured up. But it was done so well that you have to admit, you believed it.

On a more serious note corporate image is an important issue. Today, for example, Facebook is being criticized for being irresponsible in supporting the flow of accurate information through society. It must have some employees who cringe that the driveway into their corporate headquarters is named Hacker Way, which suggests this is a company with teenage-like behavior when now it has become an important component of modern society. IBM studiously avoided such traps. Amazon, which enjoyed a positive image for years, recently was criticized for its working conditions that led to an attempted unionization effort at an Alabama facility, highlighting its aggressive actions to crush the initiative. President Joe Biden even supported publicly the unionizing effort. IBM never unionized in the United States, it never had a counter-culture name for a road and it never spoke about breaking things, rather about building them. From the beginning it wanted to be seen as a firm bigger than it was and as a serious, responsible pillar of society. Today’s business titans have much to learn from IBM’s experience.

One would wonder how Letterman would treat Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Cisco, Amazon, Verizon, or Disney? He poked fun at other companies and, at least within IBM when he was popular on television, employees came up with their own Top 10 Lists all the time. If these other companies would be embarrassed by the humor, it suggests that Letterman has some business management lessons to teach them too.

Bibliography

Cortada, James W. (2019). The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Pugh, Emerson W. (1995). Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Watson, Thomas J., Jr. (1963, 2000). A Business and Its Beliefs: The Ideas that Helped Build IBM. New York: McGraw-Hill.

___________ and Peter Petre. (1990). Father, Son, and Co.: My Life at IBM and Beyond. New York: Bantam.

Cortada, James W. (July 2021). “Top 10 Signs We Are Talking About IBM’s Corporate Culture." Interfaces: Essays and Reviews in Computing and Culture Vol. 2, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, 55-63.

About the author: James W. Cortada is a Senior Research Fellow at the Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota—Twin Cities. He conducts research on the history of information and computing in business. He is the author of IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon (MIT Press, 2019). He is currently conducting research on the role of information ecosystems and infrastructures.

NFTs, Digital Scarcity, and the Computational Aura

Annette Vee, University of Pittsburgh

Abstract: Here, I draw on Walter Benjamin’s discussion of the aura of original art in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” to explore the appeal of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) in the age of digital reproduction. I explain what NFTs on the blockchain are and point to other attempts at scarcity in digital contexts, including Cryptokitties and the Wu-Tang Clan’s Once Upon a Time in Shaolin. Just as Bitcoin emerged from the 2008 financial crisis, NFTs have gained traction in the Covid-19 pandemic, demonstrating that scarce, rivalrous, positional goods are desirable even when computational networks afford perfect replication at scale.

*Please note: Explicit language quoted in this article may be offensive to some readers.

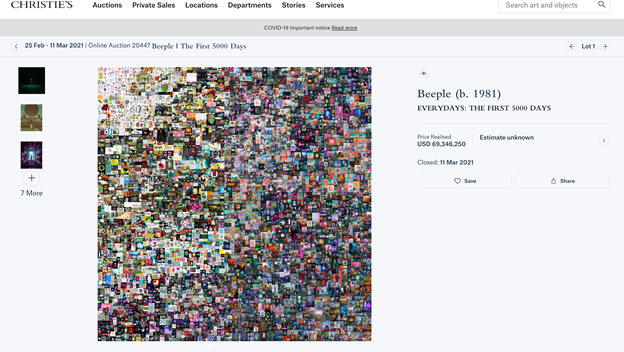

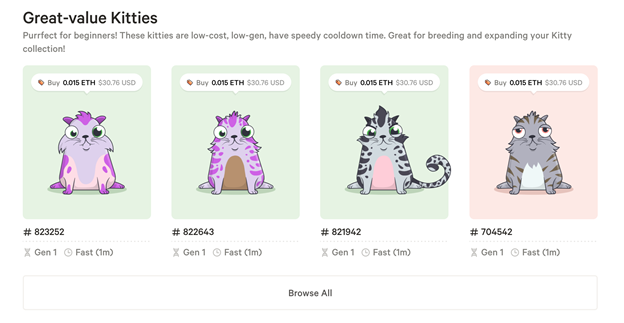

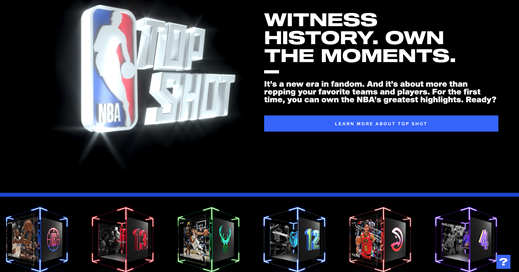

“holy fuck.” Beeple tweeted on 10:42AM Mar 11, 2021, when his artwork “Everydays: The First 5000 Days,” a jpg file measuring 21,069 pixels square, sold for $69,346,250 at auction on Christie’s online. Holy fuck, indeed: the first all-digital artwork sold at Christie’s—a composite of edgy, meme-worthy images the artist had posted every day since 2007--fetched a price in the same league as works by van Gogh, Picasso, Rothko and Warhol. In 1987, another Christie’s auction made headlines: Vincent van Gogh’s Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers (“Sunflowers”) sold for nearly $40 million, tripling the record from any previous sale of art. Putting aside comparative judgements of quality, the nearly $70 million for Everydays was a lot of money to pay for a piece of art that could be perfectly replicated and stored on any given laptop. What made Everydays more like Sunflowers than millions of other jpgs?

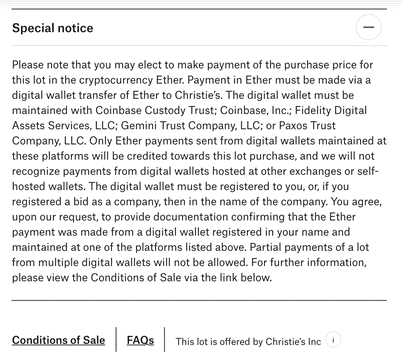

Everydays was minted on 16 February 2021 and assigned a non-fungible token (NFT) on the Ethereum blockchain. This NFT authenticates Everydays and makes it unique from another bit-for-bit copy of the same file. Where a van Gogh listing on Christie’s site might declare medium, date, and location (e.g, oil on canvas, 1888, Arles), Everydays lists pixel dimensions, a token ID, wallet address, and smart contract address. In a Special Note on the Everydays auction, Christie’s declared it would accept the cryptocurrency Ether, but only in digital wallets hosted by a select group of platforms. Implicit in the listing of these addresses, the token ID, and trusted platforms is an attempt at digital authenticity.

Digital reproduction enables exact copies of art. Even when artists employ watermarks to encourage payment for digital art, the same tools that make the images and mark them can be used to restore and replicate them. NFTs secure digital art not by changing the file itself, but by changing its provenance. NFTs attach a unique identifier, or token, to represent the art on the blockchain. Their non-fungibility differentiates them from cryptocurrency relying on the blockchain. Bitcoin or Ether, for example, are fungible: any Bitcoin spends the same as any other Bitcoin. And like the fiat currency of the dollar, Bitcoin can be spent anywhere that particular cryptocurrency is accepted. In contrast, a non-fungible token is intentionally unique and cannot be spent. But because any given NFT or cryptocoin has a unique position on the blockchain, they cannot be counterfeited. Blockchain security relies on long chains of transactions, each dependent on the previous transaction, with the entire series of transactions made public. Altering one transaction would require altering the copy of the record decentrally stored across thousands of machines simultaneously. In other words, it's effectively impossible.

When a digital piece of art has an NFT associated with it, it’s been marked as authentic by the artist or an agent with the power to authenticate it. While the digital art itself might be able to be reproduced, the version that’s on auction ostensibly has the imprimatur of the creator. It’s been digitally touched by the artist. You can, too, own an exact copy of Everydays by downloading it here. But you can’t be part of the transaction that was recorded on the Ethereum blockchain, which involved Beeple transferring the token to the winner of the auction. (For more details on the exact chain of transactions from digital file to blockchain to auction and purchase, Robert Graham offers a more technical breakdown.)

Renaissance artists such as Leonardo da Vinci painted in a studio with the help of assistants. What makes a da Vinci a da Vinci isn’t that he painted all of it, but that he painted at least some of it, and that a community of experts take some responsibility for the claim that (Langmead et al.). We can compare a da Vinci painting to Jack Dorsey’s first tweet, which has been reproduced everywhere but is now associated with an NFT (Boucher). It’s like having Jack Dorsey touch the tweet before selling it, adding his splash of paint. The scarcity is what makes it valuable; the NFT buyer owns something that others do not and cannot. One of the reasons that Salvator Mundi sold for $450 million—shattering all previous records for art auctions—is that it is one of only 20 paintings attributed to da Vinci (Langmead, et al.). Dead artists generally fetch more for their work than living artists because they aren’t making any more art (Jeff Koons holds the living artist record for his metal sculpture Rabbit, sold at 91.1 million in 2019). For NFTs as well as physical art, scarcity depends on human trust in the creator as well as the system that verifies its connection with the creator.

I own a version of Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers, which hangs on a wall in my family room. This Sunflowers is an original piece of art, has a traceable provenance, and is beautiful. It has an aura just as the one that auctioned for nearly $40 million in 1987. But the reason my copy wouldn’t fetch the same price at auction (though I admit I haven’t tried) is that the artist is Steven Vee--my dad. His paintings are highly valued in the diaspora of my hometown but are unknown to the van Gogh connoisseurs who bid at Christie’s. There’s the matter of the work’s age (15 years vs. 100 years) and materials (acrylic vs. oil paints). But the main difference between the two pieces of art is their aura: who imbued them with the aura, how they painted them, where, and who has owned them. My Sunflowers is valuable to me, but probably not to Christie's. (Although if it were, I would let it go for a mere $20million—sorry, Dad.)

Digital scarcity

Scarcity is a default attribute for a physical piece of art: both Vincent van Gogh's Sunflowers and Steve Vee's Sunflowers have multiple versions, but each individual painting is unique. Artificial scarcity has been the primary solution to the aura problem for mechanical reproduction of art. Limited print runs can ensure that a collector has one of only 20 prints, even if it’s technically possible to produce hundreds of them. Although the print may not be directly touched by the creator, its scarcity gives it value.

But scarcity is tricky with digital work. The fact that digital files are perfectly and infinitely reproducible makes it difficult to limit copies, at least once a digital file is released to another party. Perfect replication is one of the advantages of digitality, but it works against exclusive ownership. NFTs are a solution to this problem, but there have been others, each specific to its digital and social context.

In virtual spaces, scarcity emulates physical spaces. In the virtual world of Second Life, which was popular in the early 2000s and had a GDP to rival Samoa in 2009, users can build and buy property (Fleming). While the number of islands on which to build is theoretically infinite, the particular island and construction is ensured to be unique because the world is hosted by one company, Linden Lab. In Second Life, particular goods and construction could be copied and were the subject of intellectual property debates and court cases. And property ownership is subject to Linden Lab’s continued management and discretion.

In high-stakes online poker in the early 2000s, big-time players sold expensive coaching manuals as pdf files, and protected their scarcity by introducing a small variation in the version—an extra comma on page 34, for instance (Laquintano). It’s very easy to circulate a pdf: pdfs have a small file size and are easily stored and read on default programs on consumer machines. But anyone paying that much for a pdf wants security in knowing that their pdf won’t circulate easily, especially since the manuals contained poker strategies, so, like limited print runs, the pdfs lose value the more widely they are held. If the pdf manual got out, an author could trace the particular variation back to the original buyer and enforce the sales contract with social consequences in the poker community.