Interfaces

Essays and Reviews in Computing and Culture

Interfaces publishes short essay articles and essay reviews connecting the history of computing/IT studies with contemporary social, cultural, political, economic, or environmental issues. It seeks to be an interface between disciplines, and between academics and broader audiences.

Co-Editors-in-Chief: Jeffrey R. Yost and Amanda Wick

Managing Editor: Melissa J. Dargay

After overseeing the Charles Babbage Institute's Oral History Program for 26 years, initially as Associate Director and now as CBI Director, and publishing Making IT Work: A History of the Computer Services Industry (MIT Press), which discusses the remarkable growth of this sector in India, I was thrilled to attend Harvard Business School's (HBS) conference, "Oral History and Business in the Global South." This reviews the event and the ongoing “Creating Emerging Markets” Oral History Project, which has been running for twelve years. The project is led by two HBS professors: leading business historian Goeffrey Jones (who holds the Isidor Straus Chair in Business History, the same endowed chair Alfred Chandler long held) and standout scholar of Entrepreneurship and Strategy Tarun Khanna (who holds the Jorge Paulo Lemann Professorship). I also reflect on “Creating Emerging Markets” in terms of methodology, products, and uses relative to other oral history programs including CBI’s.

The design of Jones’ and Khanna’s conference was tremendous, much like the leadership of their oral history project. HBS Research Associate Maxim Pike Harrell provides skilled coordination to the project, and he saw to every detail to make the event run flawlessly. At the end of the essay, I also briefly discuss the remarkable Baker Library, of which, attendees received a wonderful behind-the-scenes tour from Senior Director of Special Collections Laura Linard.

The HBS event and HBS oral history project connect to computing and the digital world in many ways. These points of connections include both producers and users of digital technology in business in the Global South. Additionally, HBS is developing enhancements to generative artificial intelligence tools to better facilitate the use of their oral history resources. While I highlight these as a part of this Interfaces essay, my discussion is not limited to the digital realm.

The quality of every paper at this conference was excellent. While I mention them all below, I discuss a handful in a bit more detail. This is merely to offer a greater sense of the event and to add depth to the review. The conference was organized around themes of oral history methods, research uses, teaching uses, gender, and Global South geographies (Africa, Latin America, and India).

From Bollywood to Augmented Retrieval with Generative AI

The conference kicked off with a panel on “New Approaches to Building and Using Oral Histories,” which was expertly framed by convener Susie Pak, a Professor of History at St. John’s University. The opening speaker was Sudev Sheth, a historian and international studies faculty member of the Lauder Institute at Wharton School of Management, University of Pennsylvania. This was the perfect start to this event, as it offered a rich framing of oral history relative to other potential, but sometimes absent or unavailable resources such as archival collections. As such, Sheth spoke of oral history as “Unconventional Sources,” drawing from his collaborative research on the history of race and gender in Bollywood, India’s film industry. Bollywood, with fewer capital resources, produces far more films annually than Hollywood and has for decades.

For many industries, topics, and themes in business history globally, archival records either were not retained, processed, and preserved, or are not accessible to academic and other researchers, for instance, closed corporate collections. The lack of available archives is even more pronounced in the Global South where resources for archival preservation are often scarce. Sheth’s insightful talk demonstrated how oral history was essential to studying, enlivening, and giving voice to marginalized historical actors. He did this with a case study on race and gender discrimination in Bollywood. Sheth demonstrated how Bollywood, for decades has privileged lighter-skinned actors on screen, as well as presented women in submissive and stereotypical ways, and lacking in agency. He highlighted a disturbing tendency in Bollywood to have long scenes of men dominating women, including gratuitous rape scenes. Sheth then presented video oral history snippets of Bollywood women actors who explained how they condemned and strongly resisted this practice.

This recovery of otherwise lost voices rang true to me, and it is exactly why at the Babbage Institute we have aimed at doing more interviews with women programmers, systems analysts, entrepreneurs, and computer users over the past two decades. This includes a project past CBI Director Thomas Misa did for the Sloan Foundation on women programmers and one I did on women entrepreneurs in software and services. Similarly, to HBS “Creating Emerging Markets,” we often use these oral histories, along with available archival and other research, in our publications. More importantly, these oral histories become resources for others, especially academics and graduate students, to use. As both a research institute and the leading archive for the history of the digital world, CBI oral histories open up rich archival collection development opportunities.

A difference between CBI relative to “Creating Emerging Markets” is we use video or audio recordings only to create transcripts that are edited for accuracy by interviewees and interviewers. This extends from our research infrastructure mission. It might reduce the educational use of the interviews (though there are some, as we see syllabi online assigning them and daily spikes in usage). “Creating Emerging Markets,” likewise, produces edited transcripts for research, but also creates professional video and snippets. This enables HBS’ collection to facilitate tremendous educational opportunities, which fits HBS so well, a school that sets the standard and influences business and management education throughout the world like no other. HBS does this through its exceptional faculty and its unparalleled (both in size and quality) 50,000 HBS-published case studies.

For those interested in this work on the history of Bollywood I would highly recommend Sudev Sheth, Geoffrey Jones, and Morgan Spencer’s compelling article, “Emboldening and Contesting Gender and Skin Color Stereotypes in the Film Industry in India, 1947-1991.” This was published in the Autumn 2021 (95:3) issue of Harvard Business Review.

The second paper of the opening session, while quite different, was equally engaging and spoke to issues of preservation. Vice President for Communication of Sweden’s Centre for Business History Anders Sjöman spoke on the model of his nonprofit organization. The Centre for Business History (CBH) is a large nonprofit with a wholly owned subsidiary services company. It provides archival storage, processing, editorial, historical analysis, writing/publishing, and related services to companies in Sweden. The CBH has hundreds of clients, and they include globally recognized names such as IKEA and Ericsson. The nonprofit is owned by its members, and the companies it works with to meet their history and archives needs. At 85,000 linear meters of documents, photographs, film, and video, it is one of the largest business archives in the world.

In the 1990s, as a doctoral student in history specializing in business, labor, and technology, I was introduced to and found organizational history and consulting fascinating. At the time, I worked as a researcher/historian for The Winthrop Group, a prominent US-based business history and archives consultancy located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. For three years I helped to research and assist with writing a major Harvard Business School Press book on the Timken Company (Pruitt w/ Yost, 1998). Since then, in addition to my faculty and center director post, I have continued to do a bit of historical consulting for business and nonprofit organizations. I like the idea of a nonprofit providing archival and historical preservation and analysis services, where the companies using the services are members and co-owners. This is a model that could work well for other countries and regions of the world.

The final paper of the opening session was by HBS’ Director of Architecture and Data Platforms Brent Benson and Maxim Harrell. They discussed using augmented retrieval generation—setting limits and parameters to HBS’ “Creating Emerging Markets” resources/data—as tools to better facilitate the usage of the collections and content generation. While, generally, I am extremely skeptical and critical of generative AI (as it generates based on data without understanding the data’s contexts) and believe it introduces a host of social bias-amplifying risks and realities, I found this discussion of augmented retrieval generation interesting. I was impressed that in the presentation, and their responses to questions, the presenters acknowledged risks and were carefully considering them in developing and refining these tools to augment search and use of “Creating Emerging Markets” oral history data. Regardless, this engaging work sparked rich discussion concerning new automation tools versus or in conjunction with traditional metadata of descriptors, abstracts, and finding aids, along with Boolean search.

Oral History as a Research Tool

The second session was on “Employing Oral History in Research.” It began with Lansberg Gersick Advisors (LGA) and Harvard adjunct Devin Deciantis’ discussion of the continuity of family enterprises in high-risk environments, focusing on his work and research in Venezuela. Oral history, documentation, and learning from the past can be helpful to meeting the challenges of generational transition of family businesses. In risky environments such as that of Venezuela with its soaring homicide rate, this can be all the more daunting, and all the more important given resources are scarcer. Deciantis is a particularly gifted and thoughtful orator, and this was an incredible talk. University of Texas A&M San Antonio historian Zhaojin Zeng next gave an impressive paper on the politics of doing archival research and oral history in China, indicating there are both significant possibilities and challenges. People openly dissenting on record from the Chinese Government’s standard or preferred perspective on issues and history can face risks. Finally, Meg Rithmire, a political scientist at HBS, sparked a discussion on the differences between interviews in social science versus oral history. This includes terminology and practice with gathering, saving, processing/editing, and making interview data publicly available.

Oral History of Gender and Business in the Global South

With my strong interest in social history, and especially gender history and gender studies in business, I found the three papers on “Gender Dynamics through Oral Histories in Business” especially intriguing. The oral histories for the “Creating Emerging Market” Project have generally been conducted in-person—interviewer, interviewee, and a film crew (though experimentation with enhanced video conferencing tools is also underway with the project).

The scholar who has done more in-person oral histories for the project than anyone in the Global South, Andrea Lluch, gave two brilliant talks in different sessions of the event. Lluch holds professorships at the School of Management, University of Los Andes, Columbia, and at the National University of La Pampa in Argentina. Additionally, she is a Researcher at the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research of Argentina. Her research and oral histories focusing on women entrepreneurs span both Argentina and Columbia. Among the various lessons, she emphasized are the importance and learning possibilities from interviewing throughout the hierarchies of organizations, providing an example of drug cartels.

Rounding out this session were outstanding papers by standout business historians Paula de la Cruz-Fernández (University of Florida) and Gabriela Recio (Business History Group, Mexico City). Fernández’s talk focused on capturing circumstance and historical contingency in exploring one woman entrepreneur in Miami, Florida, in “Estoy, in Right Place,” while Recio explored several women leaders’ experiences as they tried to navigate the male-dominated business culture.

In a different setting, but with the same principle of navigating organizational hierarchies and gaining understanding, just over a decade ago, I had the opportunity to do a sponsored research project with Thomas Misa. This project examined the impact of National Science Foundation Cyberinfrastructure (FastLane & internal e-Jacket) on the scientific and engineering research community it serves, as well as NSF as an organization. It was an oral history-based research project as few documents existed. We conducted in-person oral histories with four hundred people at 29 universities (vice presidents for research, deans, PIs, sponsored research administrators, and department administrators) and at NSF (top leadership, division directors, program officers, administrative assistants, and clerical staff). Our understanding of universities, NSF, and social (race and gender) and research impacts were so thoroughly enhanced by getting the perspectives of those at the lower levels of organizational hierarchies. We published a book from this research, FastLane: Managing Science in the Internet World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015).

Sessions four and six of the HBS conference explored “Oral History and the Creation of Knowledge” in two large regions, Africa, and Latin America, respectively. These sessions served as broad reminders of how archival infrastructure is sparser in some regions of the world, and thus, the critical role oral history and ethnography can play in understanding business and culture is heightened.

Political scientist and Vice Dean of Education at the University of Toronto Antoinette Handley provided an insightful talk on “African Business Elites: Changing Perceptions of Power.” Laurent Beduneua-Wang offered an intriguing examination of “Ethnography and Oral History in Morocco.” While HBS’ Marlous van Waijenburg spoke broadly on “Capturing African Histories and Experiences,” a talk which by admission and intent was not so much on oral history. Instead, it was an expert high-level overview of issues in African history and historiography and thus provided rich context.

On the topic of Latin America, Andrea Lluch gave another terrific paper, “Managing Business in Unstable Contexts,” where she focused on the instability of currency in Argentina and how adjustments in the timing of purchases, planning, and salary increases were used by consumers and producers to cope with the seemingly untenable circumstances of frequent hyperinflation. Marcelo Bucheli a business historian and political economy specialist at the University of Illinois, in turn, spoke on “Political Uncertainties in Emerging Markets” in Latin America. Finally, Miguel A. Lopez-Morell (University of Murcia) presented a co-written paper he did with business historian Bernardo Batiz-Lazo (Northumbria University) entitled, “Digital Conquistadors,” contributing strongly to our understanding of history and historiography of banking in Latin America.

Oral History and Pedagogy

The penultimate session, number five, “Employing Oral History in Teaching” was a particularly important one to the event. Tarun Khanna convened this session. In general, oral history is grossly underutilized in undergraduate and graduate education, as well as high school—both from the standpoint of drawing on oral histories to instruct, as well as teaching the skills and techniques to conduct oral history well. This session explored various strategies for utilizing and enhancing skills for oral history in education. Chinmay Tumbe of Indian Institute of Management spoke on “Best Practices for Oral History Teaching and Collection Development.” Next Sudev Sheth offered a paper entitled “Teaching Global Leadership,” and how oral history can be a helpful tool. Lastly, Arianne Evans of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education presented “Incorporating Oral History into High School Pedagogy.

“Creating Emerging Markets”

From start to finish, this was a well-designed event where themes of methods, gender, geographies, research uses, and educational uses all came together to provide a coherent and vibrant whole. Discussions following the papers after each of the six sessions, as well as during the breaks and meals, were lively. We also all received a copy of Geoffrey Jones and Tarun Khanna’s Leadership to Last: How Great Leaders Leave Legacies Behind. It is a 330-page book with a paragraph-long biography on each interviewee, and then edited passages from forty-four interviewees selected from the “Creating Emerging Markets” Oral History Project.

This book serves as both a source of management lessons from the past as well as a glimpse into a significant project and its resources. For business historians and social science researchers, these passages are short and make a reader wonder about the context of the whole interview. That said, the interviewer questions (from Khanna and other researchers) are well-constructed to elicit insightful responses. Without question, it leaves you wanting to read more. While this might seem a liability, it is not. I am certain one of Jones’ and Khanna’s goals is to bring attention to the larger project and its resources, and for me, it did just that. Further, I especially like the choices of the seven themes/chapters, each with five to eight interviewees apiece:

- Managing Families

- Committing to Values

- Innovating for Impact

- Contesting Corruption

- Challenging Gender Stereotypes

- Promoting Inclusion

- Creating Value Responsibility

In reading this terrific book, as well as visiting other select oral histories on the “Creating Emerging Markets” website, the extensive research preparation of the interviewers stands out. In our program at CBI, modeled on leading programs at the University of California, Berkeley, and Columbia University, this continues to be our practice as well. Our extensive preparation is what produces four decades of what we have long termed “research-grade” oral histories. We believe this extensive commitment to research preparation and having appropriate, well-trained, and prepared interviewers is key to our success with securing and delivering upon oral history sponsored research project support from NSF, Sloan, NEH, DOE, ACM, IBM, and others.

“Creating Emerging Markets” is producing similar research infrastructure and resources, as they also invest in video and snippets which add so much to visibility and educational use— “research and educational-grade interviews” perhaps?

Public Goods

While we are not doing the production-quality video at CBI, I serve on the History Committee of the leading professional organization for computer science the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), and for that organization we are doing production video oral histories with Turing Award winners (equivalent to the Nobel Prize for computer science) and video snippets from each of these. This undoubtedly makes them more useful in computer science education, as well as the history of computing and software. With “Creating Emerging Markets” the interviews are rich for research and education in history, sociology, management, international studies, African studies, Latin American Studies, Asian Studies, and other disciplines.

A term Geoffrey Jones used repeatedly at the conference is that their “Creating Emerging Markets” Project is producing “public goods.” I would agree that the term makes sense and is fitting for a business school and business history (I have an MBA in addition to a Ph.D. in history). When I have my CBI and historian, humanities, and social science hats on, it is what I might call public resources or historical research infrastructure—that is how I commonly speak about CBI’s Oral History Program (and archives) and the public resources it produces (full transcripts of many hundreds of two-to-sixteen-hour interviews and 320 extensively processed archival collections). “Public goods” works very well for the “Creating Emerging Markets” Oral History Project as the video snippets are engaging for audiences in education, corporate education, and the wider public who have an interest.

In its dozen years “Creating Emerging Markets” has produced 181 oral histories with interviews from thirty-four countries and its site gets 80,000 hits per year at present. The interviews on the Global South span such topics as leadership, governance, business education, family business, race, gender, political economy, and more. A link to “Creating Emerging Markets” is in the bibliography, and I highly recommend visiting this incredible resource. For historians of business and management scholars of the Global South, it is tremendously valuable. And given the well-selected video snippets, it will appeal broadly.

Oral history theory, practice, collections, and publications remain rare in emerging markets. Existing projects and the surrounding literature on both interviews and methods/techniques tend to focus more on politics and culture than business and enterprise. For instance, there are such books as David Carey Jr.’s Oral History in Latin America: Unlocking the Spoken Narrative, Anindya Raychaudhuri’s Narrating South Asian Partition: Oral History, Hassimi Oumarou Maïga’s Balancing Written History with Oral Tradition: The Legacy of the Songhoy People, and Patai Daphne. Brazilian Women Speak: Contemporary Life Stories. As such “Creating Emerging Markets,” importantly, is filling an important void, as it also does much more.

“Creating Emerging Markets” is creatively and expertly building new possibilities in the business oral history space and, importantly, intersecting with the targeted geography of the Global South. Through its use of experienced and diverse business historians, management scholars, and social scientists as interviewers, through the video teams and well-selected snippets to highlight, through the development of enhanced configurable and automated searching and generation techniques, and through the edited transcripts it is innovating in methods, tools, and thematic and geographic targets in ways that strongly advance research and education opportunities in understanding emerging markets and their political economy and cultural milieu.

HBS’ “Oral History and Business in the Global South,” was such an intellectually delightful event. It worked terrifically as an engaging conference on its own and also as—along with their 2022 book Leadership to Last—a coming out party for an extremely important project, “Creating Emerging Markets,” that is developing and making public wonderful research and educational resources with enormous possibilities on parts of the world and leaders and workers who contribute so much and too often are ignored. The quality of the scholarship presented, the quality and importance of the “Creating Emerging Markets” Project, and the intellectual generosity of the conveners, presenters, and audience made it special to be part of this lively and vital conversation.

HBS’ Baker Library and Its Historical Research Gems

All the events were at HBS’ Chao Center, including a reception and catered Indian cuisine dinner after the first day of the conference. About half of the two dozen or so presenters and attendees took part in a fantastic tour of Baker Library led by Laura Linard. The sublime special collections include unique archives—corporate records, annual reports, ledgers, personal papers—extensive rare books, an art collection, and much more. The records on business history date back to the 14th century, with amazing materials in that century and each one since. The thoughtfully presented display cases, elegant reading room, and art throughout the public areas of Baker Library add much to the intellectual and aesthetic allure.

In 1819 the Ecole Spéciale de Commerce et d’Industrie (now the ESCP Business School), was established in Paris. It often is credited as the first business school in the world. Harvard Business School, established in 1908, has the distinction as the first to introduce the standard Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree. Through its incredible faculty, its methods, and its unequaled published series of case studies that are used far more than any other series in business schools globally, Harvard has an outsized impact on business and management education and educating and influencing future leaders in the U.S. and around the world. The Baker Library documents this institutional history, as it also documents business history globally.

We took the elevators down to the closed stacks and saw where the Alfred D. Chandler Collection and other archival collections are held. Of particular interest to computer historians, the library has the personal/business papers of legendary Digital Equipment Corporation founder and longtime leader Kenneth Harry Olsen. Laura, in addition to giving us the group tour, was kind enough to meet with me for an hour afterward. We discussed archives and history and the respective missions of our institutions, exploring if there were areas where we might be helpful to one another in collecting. It was a wonderful discussion and the perfect ending to two engaging and intellectually exciting days at Harvard Business School.

Bibliography

Carey, David Jr. (2021). Oral History in Latin America: Unlocking the Spoken Narrative. (Routledge).

“Charles Babbage Institute for Computing, Information and Culture Oral History Program and Resources.” CBI Oral Histories | College of Science and Engineering (umn.edu)

“Creating Emerging Markets,” Harvard Business School. “Creating Emerging Markets” - Harvard Business School (hbs.edu)

Jones, Geoffrey, and Tarun Khanna. (2022). Leadership to Last: How Great Leaders Leave Legacy’s Behind. (Penguin Business).

Maïga, Hassimi Oumarou. (2012). Balancing Written History with Oral Tradition: The Legacy of the Songhoy People (Routledge).

Misa, Thomas J., and Jeffrey R. Yost. (2015). FastLane: Managing Science in the Internet World. (Johns Hopkins University Press).

Patai, Daphne (1988). Brazilian Women Speak: Contemporary Life Stories. (Rutgers University Press).

Pruitt, Bettye, with the assistance of Jeffrey R. Yost. (1998) Timken: From Missouri to Mars—A Half Century of Leadership in Manufacturing. (Harvard Business School Press).

Raychaudhuri, Anindya. (2019) Narrating South Asian Partition: Oral History (Oxford University Press).

Sheth, Sudev, Geoffrey Jones and Morgan Spencer. (2021). Business History Review 95:3 (Autumn): 483-515.

Yost, Jeffrey R. (2017). Making IT Work: A History of the Computer Services Industry (MIT Press).

Yost, Jeffrey R. “Harvard Business School’s “Oral History and Business in the Global South”: A Review Essay and Reflection.” Interfaces: Essays and Reviews on Computing and Culture Vol. 5, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, 38-48.

About the author: Jeffrey R. Yost is CBI Director and HSTM Research Professor. He is Co-Editor of Studies in Computing and Culture book series with Johns Hopkins U. Press and is PI of the new CBI NSF grant "Mining a Useful Past: Perspectives, Paradoxes and Possibilities in Security and Privacy." He is author of Making IT Work: A History of the Computer Services Industry (MIT Press), as well as seven other books, dozens of articles, and has led or co-led ten sponsored history projects, for NSF, Sloan, DOE, ACM, IBM etc., totaling more than $2.3 million, and conducted/published hundreds of oral histories. He serves on committees for NAE, ACM, and IEEE, and on multiple journal editorial boards.

Management thinkers tend to fade from popularity when a new management trend arrives. These new practices appear and are followed with endless rounds of meetings, new buzzwords for the office cronies, and extra work that ends up driving employees crazy or their company out of business. But amidst all the changes in management styles, one voice kept its calm, soothing tone, with no buzzwords just firm guidance, through six decades. That voice was Peter Drucker’s.

For Drucker, management is a social function and a liberal art (Drucker 1989). He was amazed at the speed with which management emerged and became an integral part of society. In 1989 he reflected on the institution of management and how rarely in human history other institutions have been so transformative, so quickly, that in less than 150 years they have created a new world order and provided a new set of rules (Drucker 1989).

Drucker stayed relevant and was part of every manager’s vocabulary through his extensive writing and strong presence in mass media. He was the author of 39 books, translated into 36 different languages (O’Toole 2023), and he also wrote many columns for the Wall Street Journal, Harvard Business Review, The Atlantic Monthly and The Economist. In his management books, he consistently discussed, not just the function of managing, but also its social impact. It was clear to Drucker that management was so pervasive as a social function, that it became its Achille’s heel. He wanted to bring to the attention of managers that management must be accountable, to point out the sources of management’s power, and its legitimacy (Drucker 1989).

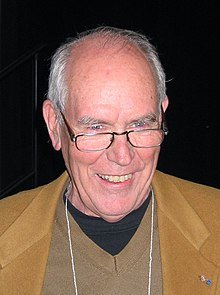

The goal of this essay is to document the enduring legacy of Peter Drucker for management theory. We aim to evaluate his clarity of vision, especially regarding the information revolution he foresaw very early, before computers were fully adopted into organizations. We use primary and secondary sources to assess how we are confronting and overcoming the management challenges that Drucker foresaw for this new century. First, we present Peter Drucker, the person, then we discuss the historical validity of using the term “guru” when referring to Drucker. Next, we present a review of Chapter 4, “Information Challenges” of his 1999 book, Management Challenges for the 21st Century to evaluate his incisive commentary regarding the impact of information, information systems and information technology in institutions and society. Finally, we conclude with a short discussion about where the Information Revolution has taken us, as of 2023.

Peter Drucker, The Person

Peter Ferdinand Drucker (November 19, 1909 – November 11, 2005) was born in Vienna under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where his father, Adolf Drucker, was a high-level civil service lawyer. His household was a place where intellectuals and high government officials gathered regularly, among them Joseph Schumpeter (Austrian-born, American economist and Harvard University Professor), and his uncle Hans Kelsen (Austrian jurist and philosopher). At eighteen, after finishing his studies at Döbling Gymnasium, and having difficulties finding a job in post-World War I Vienna, he decided to move to Hamburg, Germany

Drucker became an apprentice in a cotton trading company. He started writing for the Austrian Economist (Der Österreichische Volkswirt) which gave him some credentials and the confidence to pursue a career as a writer. Shortly after, he moved to Frankfurt to work at a daily newspaper. He enrolled at the University of Frankfurt where he earned a doctorate in International and Public Law at the age of 22.

He remained in Frankfurt for two more years; the rise to prominence of National Socialism and Hitler were events that caused him to leave. Some Austrians were becoming infatuated by the transformation of Germany; Drucker was not one of them. He decided to go to London in 1933, where he worked first for an insurance company and then as chief economist for a private bank. While in London, he married an old friend from the University of Frankfurt, Doris Schmitz. Together they emigrated to the United States in 1937.

The Drucker’s lived in Bronxville, New York for five years. In 1942, they moved to Bennington, Vermont where Drucker held a position at Bennington College as a professor of politics and philosophy. In 1950 they moved again, this time to Montclair, New Jersey where Drucker became a professor of management at New York University, a position he held for 20 years. In 1971, he became the Clarke Professor of Social Science and Management at Claremont Graduate School (Now Claremont Graduate University), a position he maintained until his death. He was instrumental in the development of one of the United States’ first executive MBAs for working professionals. Marciariello, in writing about Drucker’s driving force, recognizes the vast influence history, and his own early life experiences in Austria and Germany during the World Wars, had on his thinking to empower citizens of free societies, “so they would never be tempted to turn to authoritarian substitutes” (Marciariello 2014, xviii).

Peter Drucker, The “Guru”

Recognizing that “Guru” is an appropriate term from Hinduism, it has now lost its power in management studies where influencers may now be used. Historically, the term has a very precise place when discussing Drucker. As historians, we bring it forward in this essay, fully recognizing that for today’s readers it may have unsavory connotations, and it does not fully comply with our current ethical values. We hope that readers may see the value of its usage without compromising any aspect of equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Drucker is considered one of the most influential management thinkers ever. He was called the “leading management guru” (Harris 2005) and an “uber-guru” (Wooldridge 2009) after his death, and was influential from the time his first book on management was published in 1954. Over the years, he authored more than 25 books that have impacted the shaping of the modern corporation. In the process, he established himself as someone who knew managers, not just theorized about them.

Brad Jackson (2001) observed the management “guru” fad since 1994, originally, as a manager seeking help and guidance, later as an adult educator facilitating access to lectures by “gurus” and finally as a researcher seeking to add to the debate about “guru” theory. He identifies the “guru” fad as a phenomenon that began during the 1980s in the United States but then expanded throughout the rest of the world. He also documents the backlash during the mid-1990s against the “gurus” themselves, but mostly against management fads or fashions. He identifies rhetoric as the key element that ‘makes’ a management “guru.” He also invites his readers to deconstruct this rhetoric and demystify the ‘doctrines of salvation’ offered by those “gurus.”

From Jackson’s analysis and critique, we see Drucker’s rhetoric not as a ‘doctrine of salvation’ but as a conversation that is open, full of possibilities, emerging from his own experiences. Drucker practiced management. He was a keen observer of his actions and was able to write about them clearly and convincingly. We can think of his writing as a report from the field. When he wrote about Ford Motor Co., Sears Roebuck, or IBM (Drucker 1954), he was, in essence, writing business history and inviting his readers to witness history with him. Then, after demonstrating the practice of management in these world-renowned organizations, he invited us to consider the social impact of management decisions.

Perhaps the aspect that resonated the most with his readers was his absolute conviction that freedom and liberty are invaluable and not always guaranteed. Something he wanted all of us never to forget.

“In a free society the citizen is a loyal member of many institutions; and none can claim him entirely or alone. In this pluralism lies its strength and freedom. If the enterprise ever forgets this, society will retaliate by making its own supreme institution, the state, omnipotent” (Drucker 1954, 460).

This was so important for Drucker that Jim Collins, popular business consultant and author of Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies (2004), when addressing participants at the Drucker Centennial on November 2, 2009, declared, “Drucker contributed more to the triumph of freedom and free society over totalitarianism than anyone in the 20th century, including perhaps Winston Churchill” (Collins 2009). His legacy is well recognized, not only by those who worked closest to him (The Claremont Graduate University named their business school after Drucker) but all over the world. Because of this, people have been joining the Peter Drucker Institute which was created in 2006 as an extension of the Drucker Archives with the mission of “Strengthening Organizations to Strengthen Society”. They convene annually to continue Drucker’s conversations. They not only want to look back to Drucker’s writings, but they also want to look forward to new ideas that can be generated out of his work. In many ways, that is in essence what gurus are, guiding lights into the future. A testament to many, Drucker is the greatest source of managerial wisdom.

Management Challenges for the 21st Century

At age 90, beyond the expected lifespan of most people, Drucker published his 34th book. In his lifetime, he witnessed an enormous transformation not only in Europe, but all over the world: two World Wars, the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, the construction and fall of the Berlin Wall, the Cold War, the emergence of China, and the ossification of many American institutions. He knew that he needed to warn his readers about what was coming in the new millennium. He started the conversation at the beginning of the 1990s with The New Realities (1989) and decided to continue the conversation regarding the challenges management would face in the new century with Management Challenges for the 21st Century (1999).

Drucker sought to discuss the new paradigms of management and how these paradigms had adapted and changed toward the end of the 20th century. He wanted us to change our basic assumptions about the practice and principles of management. He concentrated on explaining the new information revolution by discussing the information executives need and the information executives owe. He brought the discussion of the knowledge worker productivity to the front and center.

Information Challenges

Drucker starts Chapter 4 of his 1999 book with a declaration:

“A new Information Revolution is well underway. It has started in business enterprise, and with business information. But it will surely engulf ALL institutions of society. It will radically change the MEANING of information for both enterprises and individuals.”

This declaration identifies two issues that we can use to check how accurate he was in his predictions. The first issue is Drucker’s claim that the information revolution will affect ALL institutions of society, and the second is about the changing MEANING of information.

Issue I: Institutions

If we were to look now for institutions that have not been affected by the information revolution, we would be hard pressed to identify one. Governments all over the world now have an online presence that was not in evident at the end of the 20th century, even in countries with small populations like Tuvalu, Palau, San Marino, Liechtenstein, and Monaco; as well as those countries with the smallest GDP, including Syria, Tuvalu, Nauru, Kiribati, and Palau. Investigations of the impact of information technology on governments have ranged from the potential of globalization facilitated by information technology and calling into question the very existence of the nation state (Turner 2016), to the influence of e-commerce on the ability of governments to raise tax revenue (Goel and Nelson 2012), and the threat to critical national infrastructures from cyber threats (Geers 2009). And more recently, how social media may facilitate social upheaval and revolution such as was experienced during the Arab Spring (Bruns, Highfield and Burgess 2013).

Businesses have been not only transformed, but also created and help bring about this Information Revolution (Google, Facebook -now Meta, Twitter -now X, Zoom, etc.) Businesses are now more prone to be impacted by cyber security threats (Kshetri 2009). Educational institutions have been transformed with massive open online courses (MOOCs). Online learning has increased to be the way most institutions communicate with their students; assignments are delivered through Learning Management Systems; and recruitment, application, and acceptance are all web-based. Banking services have moved online as people can even deposit cheques by simply taking a photograph within their banking app. Legal institutions have developed online resources that include among others the creation of Blawgs (internet-based blogs dealing with topics related to Law), and other resource repositories. The mass media has been particularly impacted. The demise of newspapers and the emergence of disinformation with ‘fake news’ or ‘alternative facts’ are just two examples of how much the information revolution has transformed these institutions.

Health Institutions have been forced to transform to deal with the explosion of medical information available on the web. Popular sites include PatientsLikeMe.com, and a multitude of communities around specific diseases: WeAreLupus.org, WeAreFibro.org (for fibromyalgia), WeAreHD.org (Huntington’s disease), etc. have switched over.

The last group of institutions we discuss is the military, obviously a group for which it is more difficult to get information since they like to keep it a secret as part of their raison d’être. At the same time, military organizations are part of the government, and as such they have a mandate to have a presence online. The US Army has its own domain (.mil), due to its heavy involvement in the development of internet technologies through partnering with research centers and universities.

Because Drucker focused on the wider societal impact of management, we are also able to examine how the information revolution has affected personal relationships through platforms like Facebook (over 3 billion users), WhatsApp (2 billion users), Instagram (1.4 billion), TikTok (1 billion), MeetUp (60 million), and others for dating and courtship. According to Cesar (2016), online dating services generate $2 billion in revenue per year in the US alone and expand at an annual rate of 5% per year between 2010 and 2015. In 2016, a study by the Pew Research Centre (Smith 2016) revealed that 15% of American adults reported using online dating sites and/or mobile dating apps and, further, that 80% of Americans who had used online dating agreed that it was a good way to meet people.

The study’s author noted that growth in the use of online dating over the previous three years had been especially pronounced for two groups that had not historically used online dating – the youngest adults (18 to 24 years of age) and those in the late 50s and early 60s. Some of the increase in use is credited to the use of gamification by apps such as Tinder, which makes choosing a ‘dating partner’ as easy as swiping to the left or right on a mobile device. Tinder now operating in 196 countries, reports its users make an average of 1.6 billion swipes per day (Tinder 2024). Lest, we think the only impact has been positive, recent academic research has shown the negative impact of partner phubbing (phone snubbing) on depression, relationship satisfaction and personal well-being (Roberts and David 2016).

It is clear from the preceding discussion that Drucker was very accurate in his declaration regarding ALL institutions being impacted by the information revolution.

Issue II: Meaning

A less obvious analysis regarding the MEANING of information is possible only by pointing out what the meaning of information was before the revolution started. Meaning is essentially a concern of Semiotics. One of the greatest semioticians of all time, Umberto Eco, was a proponent of information as a way of being human. In his essays Open Work (1962), Minimal Diary (1963) and Apocalyptic and Integrated (1964), he talks about a dichotomy between optimistic and pessimistic intellectuals who either reject or accept mass culture.

Eco finds the term information to be an ambiguous one. What interested Eco about information theory is the principle that the quantity of information (as opposed to the meaning) contained in a message is in inverse proportion to its probability or predictability, something that to him resembled the effect of art, particularly modern art. Thus, Eco argues, art in general may be conveying a much higher degree of meaning than more conventional kinds of communication. He argues that:

“…the quantity of information conveyed by a message also depends on its source … information, being essentially additive, depends on its value on both originality and improbability. How can this be reconciled with the fact that, on the contrary, the more meaningful a message, the more probable and the more predictable its structure?” (Eco 1989, 52).

It was clear enough for Eco that “meaning and information are one and the same thing” (Eco 1989, 53). He is puzzled by the practicality under which the new information revolution started. The intellectuals behind the new information age, in a very myopic, practical way created the Millennium Bug (or the Y2K Bug) not due to ignorance, but out of lack of vision. Eco was puzzled by programmers who didn’t anticipate the date problem 50 years down the road, but the Millennium Bug was a business decision to keep costs down when digital storage space was highly expensive.

Eco’s sense of amazement is also about the greatest repository ever built, the World Wide Web. He is especially concerned about how digital information is never forgotten, allowing us to re-interpret it, constantly, giving it a sense of fluid meaning, until we reach information overload: “To my mind, to have 14 million websites is the same as having none, because I am not able to select” (Eco et al. 1999, 192).

That is a good way to start to see those who immediately accepted the information revolution, a.k.a. the information age, and those who dismissed it while continuing their existence without questioning the impact that information would have on their lives. Among the ‘integrated,’ John Seely Brown, along with Paul Duguid, published The Social Life of Information (2000) to document the meaning of information in our social life. They start by reminding us of how, at one time, the lack of information was a problem: “It now seems a curiously innocent time, though not that long ago, when the lack of information appeared to be one of society’s fundamental problems” (Brown & Duguid 2000, 12).

They document how chronic information shortages threatened work, education, research, innovation, and economic decision-making. They remind us throughout the book that, “we all needed more information” as well as how “for many people famine has quickly turned to glut.” This is a good indication that the meaning of information has changed for most of us.

Issue III: Concepts

Drucker also indicates that the information revolution is “a revolution in CONCEPTS” (Drucker 1999, 97); by this he meant that it was not about Information Technologies (IT), Management Information Systems (MIS), or Chief Information Officers (CIOs). He accused the information industry—the IT people, the MIS people, the CIOs—of failing to provide information by being more interested in the technology than the information side of their mandate.

“So far, for fifty years, Information Technology has centered on DATA—their collection, storage, transmission, presentation. It has focused on the ‘T’ in ‘IT.’ The new information revolutions focus on the ‘I.’ … What is the MEANING of information and its PURPOSE?” (Drucker 1999, 97).

He was correct on some issues but missed one of the biggest transformations of this industry: going from IT to information and communication technology (ICT) with the arrival of Apple’s iPhone in 2007. Indeed, people were not looking for information when buying an iPhone, but this piece of technology redefined our interaction with technology, from keyboard-enabled communication to a freer way to get what we want, anywhere, anytime. Not only that, but this device was also so revolutionary that it reshaped many industries. The mobile phone giants, Nokia, Blackberry, Samsung, etc., were not prepared, and their businesses were completely changed. Digital cameras have almost disappeared since the smartphone allows us to always have a camera with us. Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs), launched in 1996, were required to supplement the capabilities of mobile phones, but disappeared as well since they were no longer needed when carrying a smartphone. This led to the demise of world leader, Palm Inc. Even Apple’s own iPod was cannibalized by the iPhone since people could now use their phones to listen to their iTunes collections, and after the rise of Spotify, streaming music is the new way to listen to it.

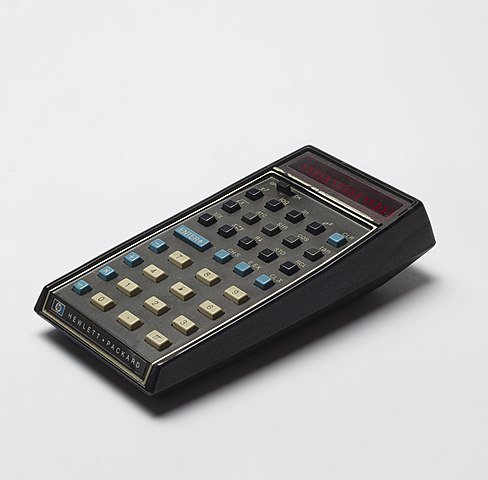

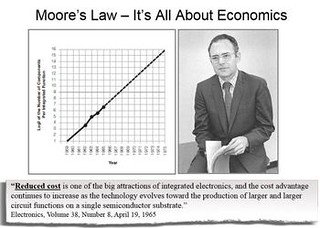

Historically speaking, the information industry needed to concentrate on technology first since it emerged in a world of analog technologies. To go fully digital, a completely new set of skills was needed. Since everything was new, there were several options tested, and if companies jumped too early into one, they ran the risk of becoming obsolete very quickly. The race for the personal computer left many big players, including IBM, with serious losses. In those fifty years that Drucker mentions in his statement, the world went from very expensive room-sized mainframe computers to affordable portable laptops; from magnetic tapes to punched cards to 5¼” and 3½” floppy disks; from 2,000 to 760 million instructions-per- second. The industry needed to be focused on technology until the technology was good enough to deliver that sense of instant connectivity, 24/7, anywhere. Therefore, businesses needed to play a game of either wait-and-see or jump-on-board into an unknown future. Following Rogers’ (1962) Diffusion of Innovation Theory: Innovators à Early Adopters à Early Majority à Late Majority à Laggards.

The aspect that Drucker wanted to highlight in his assessment is that users, especially executive users, needed to engage in the information revolution not from a perspective of being seduced by new tools, but by being able to do things that were not possible before without these technologies. That is why he stressed the importance of concepts, concepts that would emerge only by questioning what those users were doing, “top management people during the last few years have begun to ask, ‘What information concepts do we need for our tasks?’” (Drucker 1999, 100).

In answering that question, we have seen the transformation of business computing purpose from Decision Support Systems (DSS) to Executive Information Systems (EIS), to Business Intelligence (BI), to the current Business Analytics (BA). Also, the role of data as a by-product of Transaction Processing Systems (TPS), has transformed into data as an asset, and data as the new oil. Are these new concepts or just slogans?

To grasp the sense in which Drucker used the term ‘concept’ in his analysis of the information revolution, perhaps is important to remember that he taught philosophy at the beginning of his career as an academic at Bennington College. In his autobiography, Druker writes about Karl and Michael Polanyi, and even though he does not mention Ludwig Wittgenstein specifically, Wittgenstein was living in Vienna at the same time as Peter Drucker was. This time has been documented as the first Vienna Circle, a time when many revolutionary new ideas in philosophy were emerging. More than an etymological definition we need an epistemological one of ‘concept’ to capture the sense that Drucker may have had when writing about informational challenges.

Peacocke (1996) discusses “concepts” as a way of thinking about something. One object in particular, a given property, a relation, perhaps an entity. He emphasizes that concepts have to be distinguished from stereotypes. He reminds us that while the theory of concepts is part of the theory of thought and epistemology, the theory of objects is part of metaphysics and ontology. “…a theory of concept is unacceptable if it gives no account of how the concept is capable of picking out the objects it evidently does pick out” (Peacocke 1996, 74).

Even though Drucker is writing about the information revolution at the end of the 20th century, he was very clear, since The Practice of Management, that information, to him, is “the tool of the manager” (Drucker 1954, 412). He explains what that concept means to him through the way he explains what he means by listing the collection of ‘objects’ he picks out:

“The manager has a specific tool: information. He does not ‘handle’ people; he motivates, guides, and organizes people to do their own work. His tool – his only tool – to do all this is the spoken or written word or the language of numbers. No matter whether the manager’s job is in engineering, accounting, or selling, his effectiveness depends on his ability to listen and to read on his ability to speak and to write. He needs skill in getting his thinking across to other people as well as skill in finding out what other people are after … must understand the meaning of the old definition of rhetoric as ‘the art which draws men’s hearts to the love of true knowledge’” (Drucker 1954, 413).

The choices are clear. For Drucker, from the time he started writing about the practice of management up to his discussion of the information revolution, reading, writing and arithmetic, and rhetoric, are the concepts that make information useful to managers. After nearly fifty years, he recognizes that not much has changed for executives:

“In business across the board, information technology has had an obvious impact. But until now that impact has been only on concrete elements—not intangibles like strategy and innovation. Thus, for the CEO, new information has had little impact on how he or she makes decisions. This is going to have to change” (Drucker 2002, 83).

Perhaps for no one else but Drucker, at the dawn of the 21st century it was clear that data alone would not suffice to compete and win in the new economy. Drucker puts the onus on each knowledge worker by correctly pointing out that “no one can provide the information that knowledge workers and especially executives need, except knowledge workers and executives themselves” (Drucker 1999, 124).

Conclusion

Drucker was correct when in 1999 he warned us of the challenges we would be facing in the 21st century, especially those regarding the new information revolution. Looking at the three issues that he brought to our attention: Institutions, Meaning and Concepts, we can see that in the last 23 years, all of them have had a transformation due to the ICTs that have emerged (and continue to emerge). Institutions now have a digital reality that keeps them present to their constituents 24/7, anywhere and everywhere.

The meaning of information, especially the issues of information overload, misinformation and disinformation is a constant threat to institutions and people. Privacy and security online are now aspects that were formerly not present in the digital world of management. Willingly or unwillingly, we must recognize, for example, that X (formerly Twitter) is an essential tool to take the pulse of politics. How would the world of business survive the 2020 pandemic without the emergence of Zoom?

Can concepts help us retake control of the meaning of information? That is something that the new generation of managers will have to decide. The generation that has grown up digital is starting to take its place in the workforce, and we will have to wait and see if they take this control back to its rightful owners, the people.

Drucker had a view of society that no longer describes the society we live in. He was very optimistic about what individuals get by participating in social groups. His revolution was a gentle one offering many advantages not only to managers and organizations but to simple individuals. Something that is no longer true. The revolution we are witnessing is a harsher one, with huge inequalities generated between those with access to these technologies and those without; corporations that are valued by intangibles with little regulation; the emergence of Neoliberalism. A revolution biased against marginalized groups either by race, gender, disability, or access to education.

Looking at primary and secondary sources, we have opened a conversation regarding how organizations are confronting the challenges that Peter Drucker foresaw at the close of the 20th century. At least for us, from the perspective of the information revolution, we think that we are doing what is needed to conform to the demands of the new realities. But there is still much work to be done and having Drucker’s legacy in his writing is reassuring.

Bibliography

Bruns, A., T. Highfield and J.E. Burgess (2013). “The Arab Spring and social media audiences: English and Arabic Twitter users and their networks,” American Behavioral Scientist, 57, (7), 871-898.

Brown, J. S., and P. Duguid. (2000). The Social Life of Information (Harvard Business School Press).

Cesar, M. (2016). “Of Love and Money: The Rise of the Online Dating Industry,” http://www.nasdaq.com/article/of-love-and-money-the-rise-of-the-online-dating-industry-cm579616 (accessed February 3, 2024).

Collins, J. (2009). Address, available as a video at: www.druckerinstitute.com/peter-druckers-life-and-legacy/tributes-to-drucker (accessed January 19, 2024).

Drucker, P.F. (1954). The practice of management (Harper & Brothers).

Drucker, P.F. (1978). Adventures of a Bystander (Harper & Brothers).

Drucker, P.F. (1989). The New Realities: In Government and Politics, in Economics and Business, in Society and World View (Harper & Row).

Drucker, P.F. (1999). Management Challenges for the 21st Century (Harper-Business).

Drucker, P.F. (2002). Managing in the Next Society (Truman Talley Books – St. Martin’s Press).

Eco, U. (1989). The Open Work (Harvard University Press).

Eco, U., S.J. Gould, J.C. Carrière, and J. DeLumeau (1999). Conversations about the end of time (Penguin).

Geers, K. (2009). “The Cyber Threat to National Critical Infrastructures: Beyond Theory,” Information Security Journal: A Global Perspective, 18, (1), 1-7.

Goel, R.K. and M.A. Neilson (2012). “Internet Diffusion and Implications for Taxation: Evidence from U.S. Cigarette Sales, Internet & Policy, 4, (1), 1-15.

Harris, K. (2005). “Peter Drucker, leading management guru, dies at 95, 11 November,” available at: www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive (accessed January 15, 2024).

Jackson, B.G. (2001). Management Gurus and Management Fashions, London: Routledge.

Kshetri, N. (2009). “Positive Externality, Increasing Returns and the Rise in Cybercrimes,” Communications of the ACM, 52 (12), 141-144.

O’Toole, D. (2023). The Writings of Drucker, in The Daily Drucker, November 12, 2023, https://dailydrucker9.wordpress.com/ (accessed February 20, 2024).

Maciariello, J. A. (2014). A year with Peter Drucker (Harper-Business).

Peacocke, C. (1996). Concepts. In Dancy & Sosa (eds.) A companion to Epistemology, The Blackwell Companions to Philosophy (Blackwell).

Ramirez, A. (2020). “Of Bugs, Languages, and Business Models: A History,” Interfaces: Essays and Reviews in Computing and Culture, Vol. 1, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, May 2020: 9-16.

Roberts, J.A. and M.E. David (2016). “My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners,” Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 134-141.

Rogers, E. (1962). Diffusion of Innovations (Free Press).

Smith, A. (2016). 15% of American Adults Have Used Online Dating Sites or Mobile Dating Apps, 11 February, available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/02/11/15-percent-of-american-adults-have-used-online-dating-sites-or-mobile-dating-apps/ (accessed February 3, 2024).

Tinder (2024). About Tinder, available at: https://www.gotinder.com/press?locale=en (accessed February 3, 2024).

Turner G. (2016). “The Nation-State and Media Globalisation: Has the Nation-State Returned — Or Did It Never Leave?” In Flew T., Iosifidis P., Steemers J. (eds) Global Media and NationalPolicies. (Palgrave Macmillan), 92-105.

Wooldridge, A. (2009). Peter Drucker: uber-guru, paper presented at the 1st Global Peter Drucker Forum, Vienna, 19-20 November, available at: www.druckersociety.at/repository/abstracts.pdf (accessed January 6, 2024).

Alex Ramirez (March 2024). “A Revolution: Drucker Saw it Coming.” Interfaces: Essays and Reviews on Computing and Culture Vol. 5, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, 23-37.

About the author: Alejandro Ramirez is an Associate Professor of Business Analytics and Information Systems at the Sprott School of Business – Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. He has a PhD in Management – Information Systems (Concordia), an MSc. in Operations Research & Industrial Engineering (Syracuse), and a BSc. In Physics (ITESM). He has been active with the Business History Division of ASAC since 2012 and has served as Division Chair and Division Editor. He is interested in the History and the stories of Information Systems in Organizations.

In the past five years, corporations have been pressured to stop just focusing on stockholders and instead also pay attention to the needs of other stakeholders: employees, communities, indeed entire societies. Many high-tech firms, and notably social media ones, are being criticized for letting fake facts proliferate threatening the very foundations of democracy and civic behavior, such as Facebook (Meta) and Twitter (X), while others are accused of treating their employees almost as if they worked in sweatshops, such as Amazon. They are not allowed to hide behind new names, such as Meta and X, and regulators are chasing them all over the world for their near monopolistic dominant positions or for treating one’s personal data in a cavalier fashion. So many IT firms are big enough that they actually affect political and social behavior across many countries. In short, they no longer are just companies within some vast economy, rather now pillars of the societies in which they operate. That is largely why so many in the public are demanding that (a) they respect one’s privacy and (b) that they take seriously the values of their customers (e.g., being environmentally friendly, inclusive in serving and hiring myriad racial, ethnic-identifying people).

CEOs are pledging to do better and to serve a broader range of stakeholders, while some are holding out. Nonetheless, it seems every high-tech firm almost anywhere is under the microscope of regulators, legislators, interest groups, customers, and societies at large. Historians, economists, business school professors, sociologists, and—just as important—some wise and experienced business leaders understand that how to deal with stockholder vs. stakeholder issues boils down to corporate values, policies, how it treats customers and employees, and their commitments to society—in short to corporate cultures. So many high-tech firms are so new, however, that they are, to be blunt about it, borderline clueless on how to shape, implement, and change their corporate cultures. Yet the growing empirical evidence is that managing corporate cultures may be more important than coming up with some clever business (product or service) strategy. College students founded Facebook in 2004, becoming the poster child for a firm that many feel is yet to be run by experienced executives, specifically Mark Zuckerberg, one of those students. Unlike at any major public firm Zuckerberg still has a majority of voting shares, which means he maintains ultimate control over Meta’s activities. Google was established in 1998, but eventually hired Eric Schmidt who was positioned in the media as the “adult” the company needed. And then there is the chaos unfolding at X (Twitter) that is causing much head-scratching.

So, if getting one’s corporate culture “right” promises peace with society and its regulators and legislators on the one hand and, as historians and business professors argue, promotes the economic success of a firm, where does a high-tech company learn what to do? In the world of IT, sources of positive examples are rare either because they are or more realistically because too many have not been around long enough to have successfully immediately effective corporate norms. A few are obvious: H-P, Microsoft, and increasingly Apple. They are obvious for being around long enough to have succeeded and made errors and corrected these to varying degrees. Old manufacturing firms, of which there are many, are not always seen as relevant case studies, although we have IBM, H-P, and Apple as potential case studies from which to learn. The most senior of these is IBM.

The hard facts about why IBM is the “Mother of All Case Studies” for the IT community is difficult to dispute. First, it was established in 1911 and is still in existence, making it the longest-running IT firm in history. Regardless of how one thinks about IBM, it survived and more often than not thrived, and when adding in the firms that originally made-up IBM, it has done so since the early 1880s.

Second, the empirical evidence increasingly demonstrates—as do my other books about the IT industry’s evolution, use of computing, and of IBM’s market share—that its tabulators dominated the early data processing industry’s supply for a half-century by 90 percent. Depending on which country one looked at, 70 to 80 percent of all mainframes came from IBM in the next 4+ decades, only dipping to about 50-60 percent in the USA due to more IT competition there than anywhere else in the world.

Third, from the 1930s to the late 1980s, IBM also dominated the conversation about the role of data processing (which included more than just about mainframes)—this third point being an important issue I have recently been studying. Attempts to shape public and regulatory opinions about Facebook (Meta), Twitter (X), Amazon, Google, and a myriad collection of Asian firms have bordered on either harmful to the firms (e.g., as is happening with X at the moment) or did nothing to move the needle either in public opinion or in the minds of their customers. My personal observations of the IT world over the past four decades have led me to conclude that the IT community has done a poor job in presenting its various perspectives and value propositions in ways that would enhance their economic and other roles in societies. That is due to mismanaging image creation and dominating the conversation—hence “everyone’s” perspective that would optimize the effectiveness of a firm. This third reason goes far to explain why so much negative press and impressions exist about, for example, social media and online merchants, despite everyone’s belief that they have no choice but to rely on these firms.

All of this is to explain why I wrote Inside IBM: Lessons of a Corporate Culture in Action (Columbia University Press, 2023). I followed frameworks and descriptions of what constituted corporate cultures produced largely by sociologists and business school scholars over the past half-century. I would recommend such a strategy for those looking at, say, IT companies. What these various studies pointed out was that there is a set of common issues to explore. Successful companies define very carefully what their values should be (e.g., at IBM’s “Basic Beliefs) that one can consider, as I phrase it, a form of “corporate theology”—it is there, remains pervasive, and people are held accountable for living it. In IBM’s case this involved providing high levels of customer service, respecting all individuals (that includes customers and citizens at large), and operating in a meritocratic environment where high quality work (“excellence”) was the expected outcome. They implement practices, policies, job descriptions, reward systems, training, and communications that support these values for decades. These are not the program-de-jour or this quarter’s initiative.

The culture experts also point out that such an ethos should attract, engage, and become part of the worldview of customers, regulators, and yes, families of employees. I devote an entire chapter just to how IBM as an institution interacted with families for nearly a century. The evidence made it very clear that this was an organized purposeful exercise, which went far to explain the nature of benefits provided and when (e.g., health insurance, pensions) and sponsored events (e.g., Christmas parties with Santa Claus, summer picnics, employee/spousal trips to Rome, Hawaii, or other resorts).

Keeping other IT companies in mind as possible candidates to study using IBM’s experience as an initial framework for how they might approach the topic, I divided my study into two large categories. The first was both an overview of theories of corporate culture and how they applied in large enterprises accompanied by specific case studies. The latter included discussions of IBM’s corporate theology, how the company functioned on a day-to-day basis (often called by scholars and employees “The IBM Way”), the role of managers in implementing IBM’s culture, how unions could not succeed in the US side of IBM, and employee benefits and relations with families, of course. I could have ended the study at this point because I had explained how IBM had developed and used its corporate culture from roughly the 1910s through the mid-1980s and have clearly documented an effective alignment of culture and strategy that proved successful. However, massive structural and technological changes in the IT world in the 1980s to the present jarred, harmed, and forced changes on IBM altering both in its strategy and culture. I tell that story right up front in an introduction to the historical study because I wanted to also reach current executives in both IBM and all over the industry about what works and does not. In fact, I tell them if all they want is “the answer” to what they should learn from IBM, that introduction is enough, along with perhaps the last chapter if they want their culture to be ubiquitous around the world. As a brief aside, IBM’s culture was universally applied and as Catholic IBM employees often pointed out, it was as consistent in values, rituals, reporting, and activities similarly to the temporal Catholic Church. And just like the Church, IBM implemented its practices essentially the same way. Its Latin was English, its bishops vice presidents, its cardinals, general managers, and so forth.

Then there is the second part of the book, in which we have a partial history of IBM’s material culture. Material culture concerns the cultural and archeological evidence left by a society or organization, in our case such items as products (e.g., computers, boxes with software in them or on floppies and tapes), baseball caps, and coffee mugs with the firm’s name on them, logoed publications, postcards of factories and other buildings, pens and pencils, and myriad other items. Business historians have, to put it bluntly, not studied these ephemera, especially the massive quantity of such objects that have been so popular in the IT industry. Access eBay and type in the name of any IT firm of your choice and you will be surprised, even shocked, at the volume of such material. These logoed items, and the objects used daily in buildings, did not come to be by accident. As a cultural anthropologist or advertising expert will point out, each carries a message, reflects a point of view, and says much about the culture of the firm—THINK signs for over a century (figure 1). But also true, as demonstrated in IBM’s case, they are tied to the purpose of the firm. A PC expert walked around wearing a PC-logoed baseball cap in the 1980s, and in the early 2000s an IBM Consulting Group employee might use a Cross pen with the gray logo of this part of IBM to make it known she was not a “box” peddler for Big Blue. And so, it went.

This book studies a number of types of ephemera to see what they reveal about IBM’s culture. These exposed a great deal normally not discussed in conventional historical monographs. For example, IBMers are considered serious no-nonsense people—an image carefully cultivated for decades in a consistent manner by the corporation that paid enormous dividends (remember “Nobody ever got fired for recommending IBM”?), but IBM had a vast long-standing humorous side to it internally. Thomas Watson, Sr. was presented as a furiously serious leader for over 4 decades while in charge of IBM. Yet he lived in a sales culture where humor and skits were the norm. See Figure 2—yes, he is wearing a Dutch wooden shoe and is smiling; he may well have just participated in a skit in a sales office; other CEOs did too.

Now look at Figure 3, which like so many floated inside the firm, showing a salesman as arrogant, elitist, and dressed quite fashionably. It reflected an attitude found in certain parts of IBM where attire was a humbler affair and where it was believed that the fastest way to build a career in IBM was through sales. Fair? True? It does not matter, because it was a company that employed hundreds of thousands of people and its divisions were like neighborhoods in a city, each with its own personality.

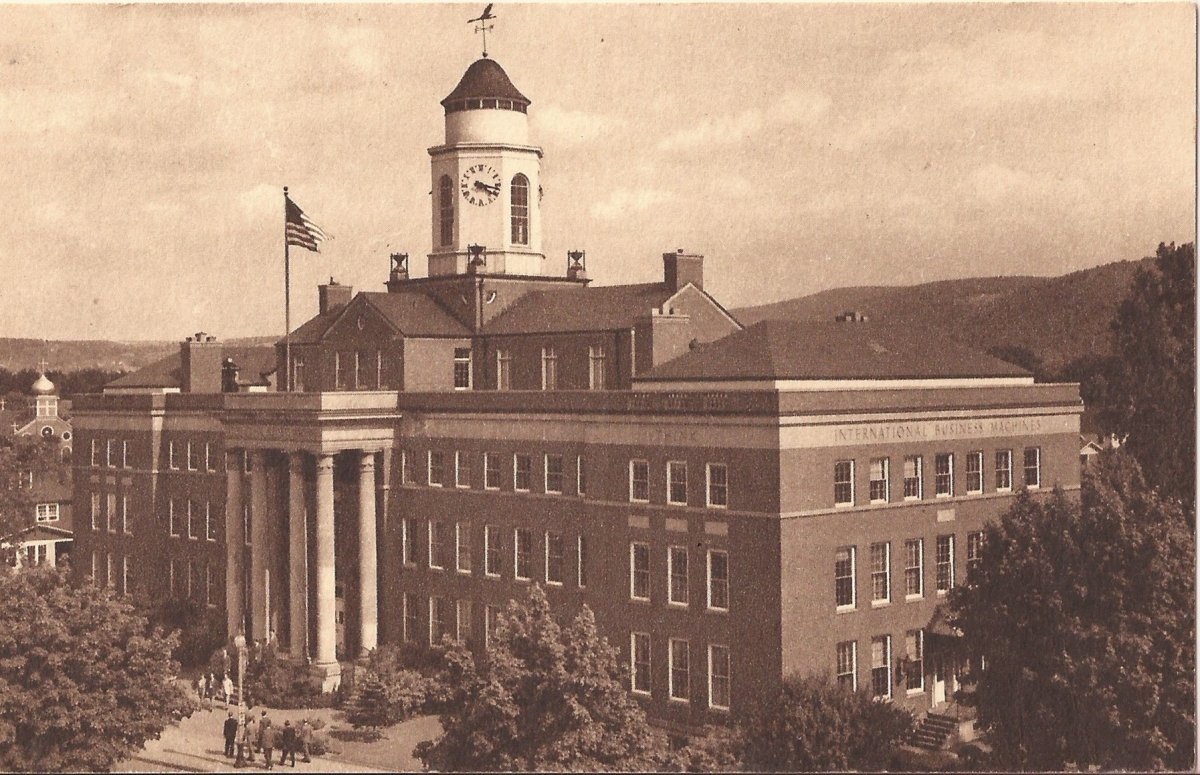

More seriously, IBM wanted the public to see IBM as solid, respectable, professional, and reliable. In the first half of the twentieth century companies all over the world produced postcards to depict such images; IBM was no exception. Watson came from what was considered at the time one of the best run most highly regarded firms in America—NCR—before he commissioned postcards that looked just like the ones he remembered at his prior firm. As IBM expanded and built new buildings, out came more postcards. Some modeled Harvard’s buildings with their trademark cupolas; these were obviously communicating that they were part of a financially solid enterprise. As the firm moved to establish itself as big and elite, a customer or visitor could only get these postcards if visiting such buildings, physically interpreting them. A customer could think, “I am privileged, I was able to be involved in a meeting with the Great IBM.” These were also mementos—think memorializing links—of someone’s connection to IBM (see Figure 4).

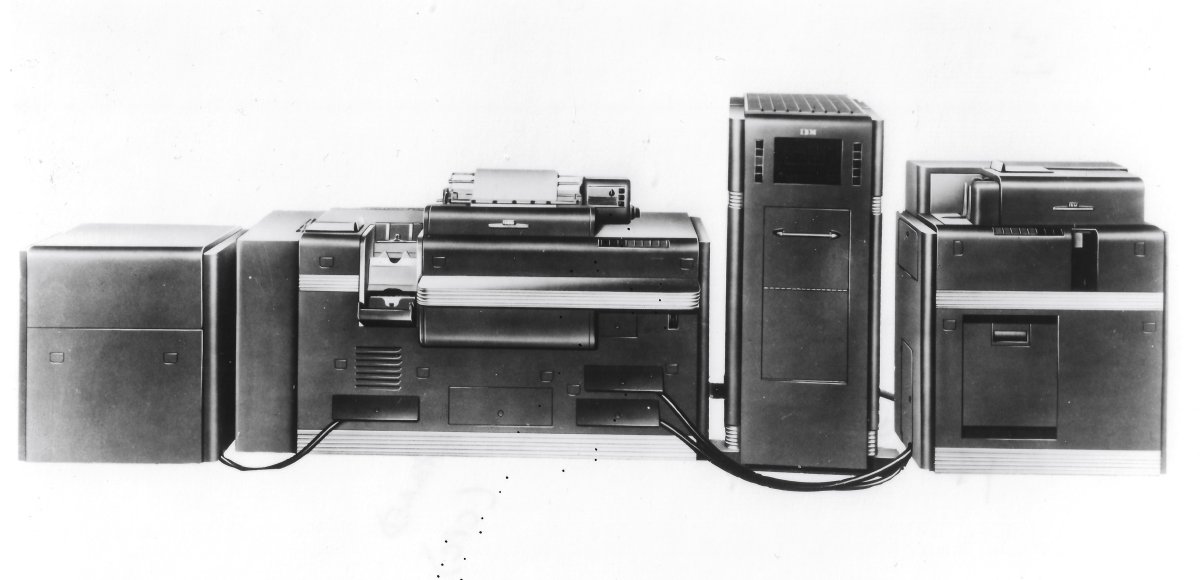

There is a detailed discussion of IBM’s machines complete with some of the most boring product pictures; every IT company produces such images; CBI has an impressive collection of these from many firms that no longer even exist. But these photographs carry messages and reflect corporate attitudes. For example, look at Figure 5 (3.3 p.95). We can agree that it is boring, that it would not win the photograph any prize. However, this 1948 image signaled that IBM thought of this new generation of hardware similarly as it had tabulating equipment for decades, seeing it as a data processing system, not a collection of various products (known colloquially as “boxes”). Note the discrete exposure of cables in front of the machines connecting them all together such that one entered data at one end and out came answers and reports on the other. In real life, those cables would have either been placed behind the machines out of sight or later under those ubiquitous, white-squared floorboards known later as “raised floors.” Dozens of product pictures later, the message was the same: modern, integrated, fashionably designed, big, powerful, and reliable.

IBM also became one of the largest publishers in the world; indeed, there is some dispute about whether it was THE largest one; I take the side of those who think it was the second biggest after the U.S. Government Printing Office. No matter, it was massive, making any collection of academic or trade publishers look tiny in comparison and its publication practices were far more efficient and different than what we experience as authors outside the firm. In the longest chapter in the book, I explain how many publications there were (are); how they were written, published, and distributed; and their purpose. It was not just to persuade someone to buy IBM, or how to use these machines, for the IBM customer engineers how to do that and keep them running or systems engineers how to debug problems. From its earliest days, IBM wanted to dominate what “everyone” worldwide thought about the use of all manner of data processing: customers, opinion makers, academics, executives, politicians, military leaders, employee families, and entire company towns (e.g., where IBM had factories), among others.

This study demonstrated that it had to have a consistent message across all its publications, had to do this for decades, and in sufficient volume to be heard above the din of its competitors and even those publishing in the IEEE, ACM, and trade houses producing books on computing (e.g., Prentice-Hall, Wiley, even MIT). Many of those other outlets published articles and books by IBM authors, again for decades (by me too). But, too, computing was complicated and required a vast body of new information. The chapter starts with a quote of one programmer: “I had perhaps 20 pounds of manuals at my desk to be able to do my job. It was a very paper-intensive time.” An IBM customer engineer called in to fix a machine—and there many thousands of them—came to a data center armed with a fat volume that looked like a Bible with a similar trim size and black leather binding, which they used every working day of their careers. In fact, when they retired, they often kept their personal copy barely suggests the quantity of pages and dense technical text, but the chapter does not spare the reader. Dictionaries of IT terms ran into the many hundreds of pages and had to be constantly updated throughout the second half of the twentieth century, indirectly serving as testimonials to the vast amount of incremental changes that occurred in technology. Pages were replaced in the customer engineering black volumes once or twice weekly with updated ones, done for decades.