SAFL’s Judy Yang and Miki Hondzo Awarded LCCMR Grant to Tackle Harmful Algal Blooms in Minnesota

August 2022 – Judy Yang, SAFL Faculty and Assistant Professor of Civil, Environmental, and Geo- Engineering, has recently been awarded a 326K grant from the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR) for a project titled “Mitigating Cyanobacterial Blooms and Toxins Using Clay-Algae Flocculation.” Alongside Miki Hondzo, SAFL Faculty, Professor of Civil, Environmental, and Geo- Engineering and co-PI on the project, and other partners, Professor Yang will investigate solutions to excessive algae growth in Minnesota’s lakes and rivers.

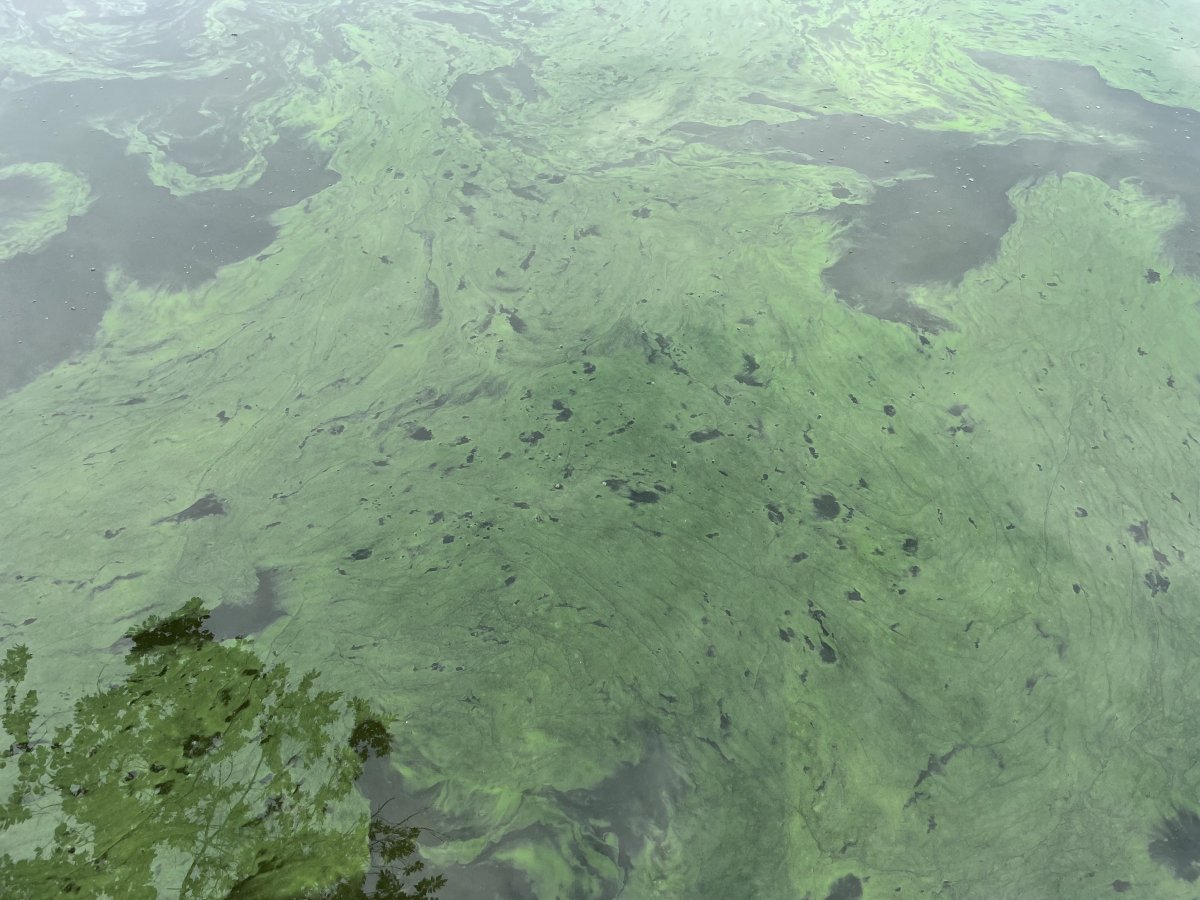

Exacerbated by climate change, excessive algae growth is a real and growing problem in the Great Lakes region and across the world. While many algae are not toxic, many freshwater algae such as Microcystis aeruginosa can produce toxins, poisoning humans and animals and contaminating drinking water. These algae colonies are known as Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) and can have negative, even fatal, effects.

“We know HABs are becoming a greater problem in Minnesota,” says Dr. Shahram Missaghi, Water Resources Coordinator for the City of Minneapolis and partner on this project. “We’re doing a lot of prevention - but we also have to deal with the excessive algae growth at hand.”

In Minnesota, cyanobacterial blooms, a specific type of HAB, are widespread in lakes and rivers, endangering the health of fish, animals and Minnesotans. Every year, hundreds of millions of dollars are estimated in fishery and tourism losses in the Great Lakes because of HABs like this. While preventing these blooms from forming in the first place is key, knowing how to mitigate them once they have occurred is also of critical importance.

This is where Professor Yang and her team steps in. With funds from LCCMR, they will research the use of clay-algae flocculation in Minnesota’s lakes and rivers over the next three years.

“To protect Minnesotans and our wildlife and water, it is critical that we develop an environmentally-friendly method to mitigate HABs,” says Professor Yang. “My team is proposing to do this using natural materials like clay, which can stop these HABs from growing and remove the toxins they produce from our lakes and rivers.”

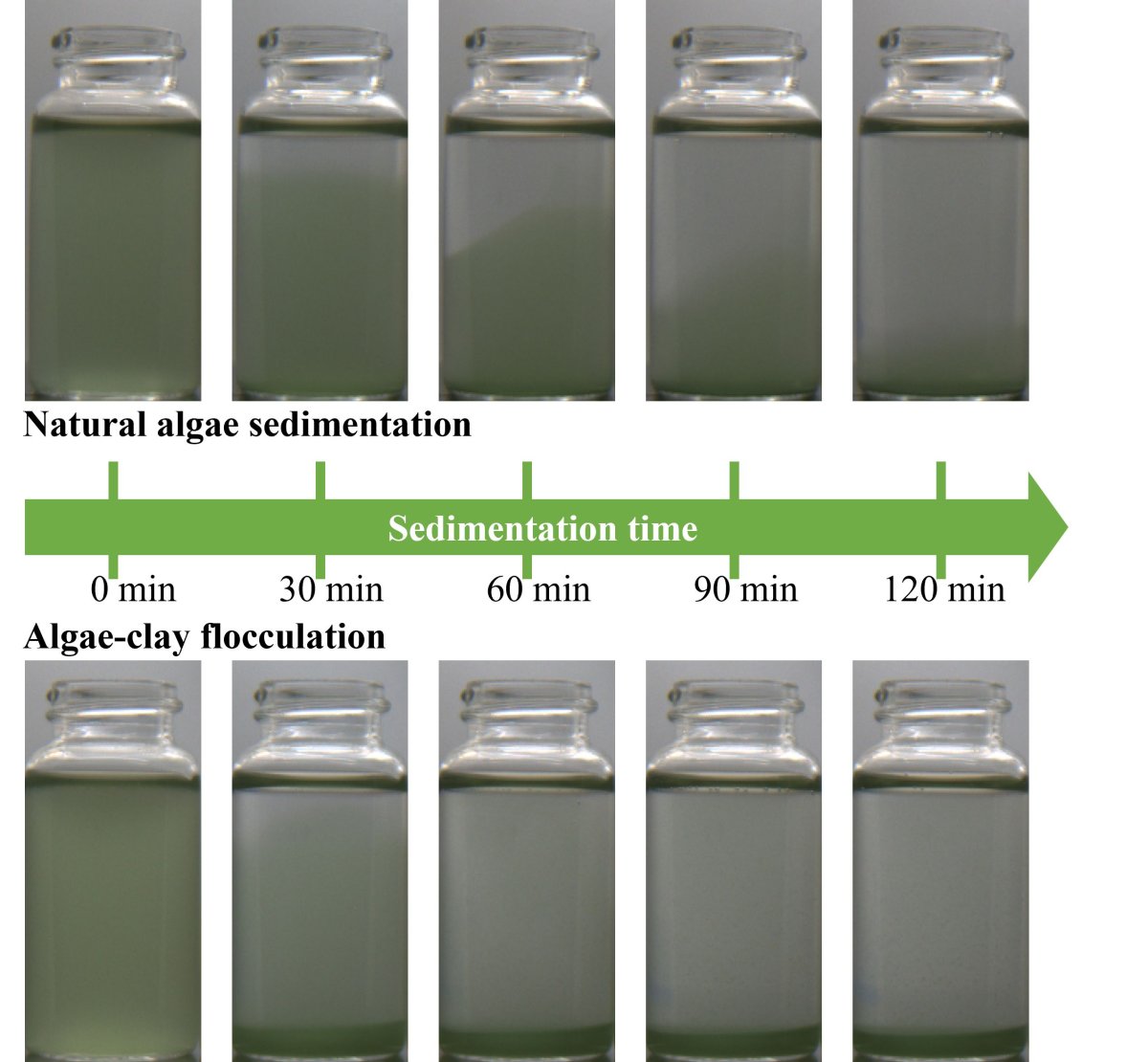

Clay-algae flocculation is one of the most promising strategies to mitigate cyanobacterial blooms. When clay - a natural material present in soils - is sprayed into contaminated water, it causes cyanobacterial cells to flocculate, or clump, and sink to the bottom. Once the cells are buried in the sediment, the majority of the toxins are removed from the water and most of the cells die due to lack of oxygen and light.

While clay-algae flocculation has successfully controlled cyanobacterial blooms in Eastern Asian Countries for over 30 years, this strategy has not yet been researched or deployed in Minnesota’s cold, freshwater lakes and rivers. Beginning with experiments in SAFL’s microfluidic channels and artificial lake and eventually advancing to study ponds and lakes, Professor Yang and her team will investigate the most effective clay-algae flocculation method for removing cyanobacteria cells from Minnesota's waters. Additionally, the team is interested in experimenting with locally-sourced clay, making this a sustainable solution to mitigating HABs.

Once Professor Yang’s team has developed this method, they will share it widely through a calculator. This calculator will assist practitioners in applying clay to their own water bodies, taking into account water depth, bloom size, temperature, water chemistry and more. In this work, Professor Yang is partnering with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and Minneapolis Public Works.

“We know you’ll have more HABs in the future,” says Dr. Missaghi. “And this may be one of the best ways we can address and mitigate them.”