Ancient Meteorite Deposit in Minnesota

A fireplace at the historic Gunflint Lodge in northeastern Minnesota (pictured to the right) was constructed of some very unusual rocks. Their origin had puzzled visiting field geologists for decades.

However, recent evidence now indicates that the rocks derived from one of the world's oldest and largest meteorite impact events.

2 billion years ago...

Imagine central North America nearly 2 billion years ago, as a meteorite 10 miles in diameter strikes the Earth near what is now Sudbury, Ontario (Figs. 1 and 2). The force of the collision vaporizes the meteorite and much of the ground near the impact site, forming a crater more than 150 miles wide(1). Shock waves race from the impact, deforming the Earth’s crust around the crater’s edge, and causing earthquakes that shatter the ground hundreds of miles away(2). Within seconds, a cloud of ash, rock fragments, gases, and droplets of molten rock—known collectively as ejecta—rises through the atmosphere and begins to spread across the globe. In this turbulent cloud of ejecta, some of the ash and vapor coalesces—much like hail stones form during thunder storms—to create small spheres called accretionary lapilli. The lapilli and other ejecta are propelled from the impact site at supersonic speeds. In the shallow ocean that covered much of the region, the impact generates huge tidal waves (tsunamis) that cross the ocean surface, mixing together rock fragments and ejecta. Over time, this material is buried by younger sediments, cemented together, and fused by molten rock to form a solid layer.

Photo courtesy of Don Davis (via https://images.nasa.gov/details-ARC-1991-AC91-0193.html)

Sudbury impact layer

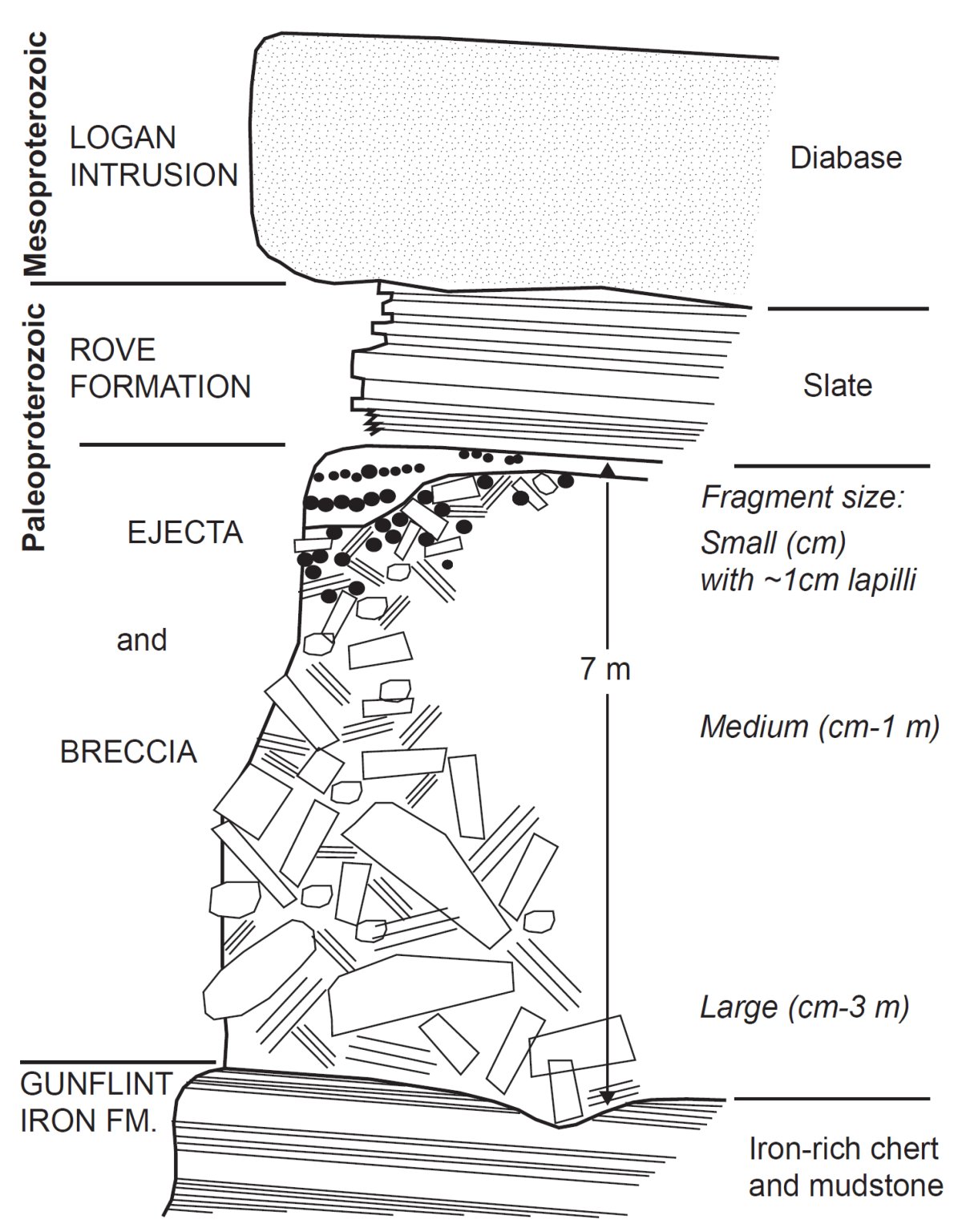

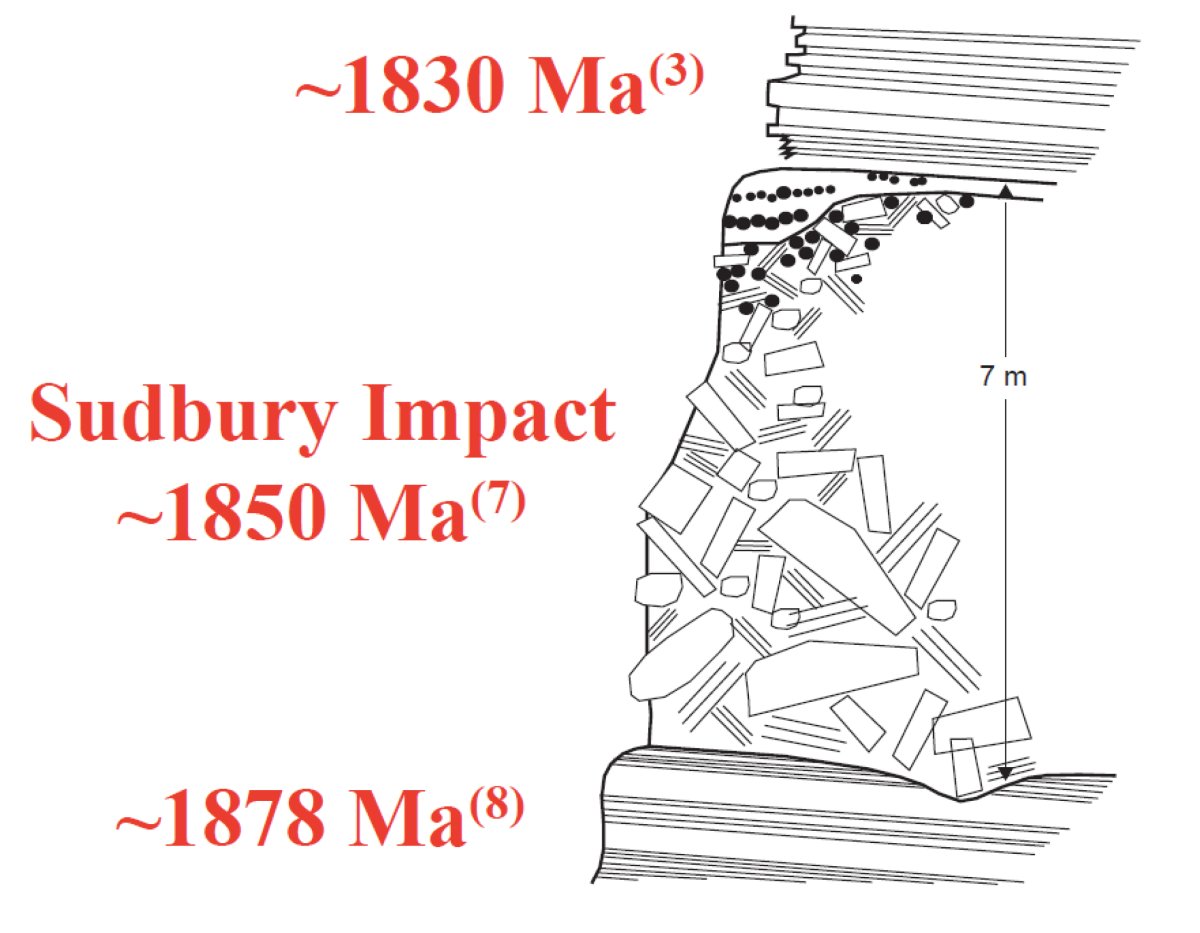

In 2007, a layer of rock was discovered in Minnesota that is thought to have formed during the Sudbury meteorite impact event. The layer is exposed near Gunflint Lake, nearly 500 miles west of the impact site at Sudbury (see Fig. 2). It is sandwiched between the Gunflint Iron Formation below, and slate of the Rove Formation above (Fig. 3). Both of these formations were deposited as muddy, oceanic sediments. Nearly a billion years later, these rocks were intruded by magma (Logan Intrusion) as part of a major continental rifting event.

Most of the impact layer consists of breccia—a mixture of fragments broken from the underlying iron-formation and cemented together (Fig. 4). These fragments represent pieces of seafloor that were ripped loose by impact-related earthquakes and carried down a submarine slope.

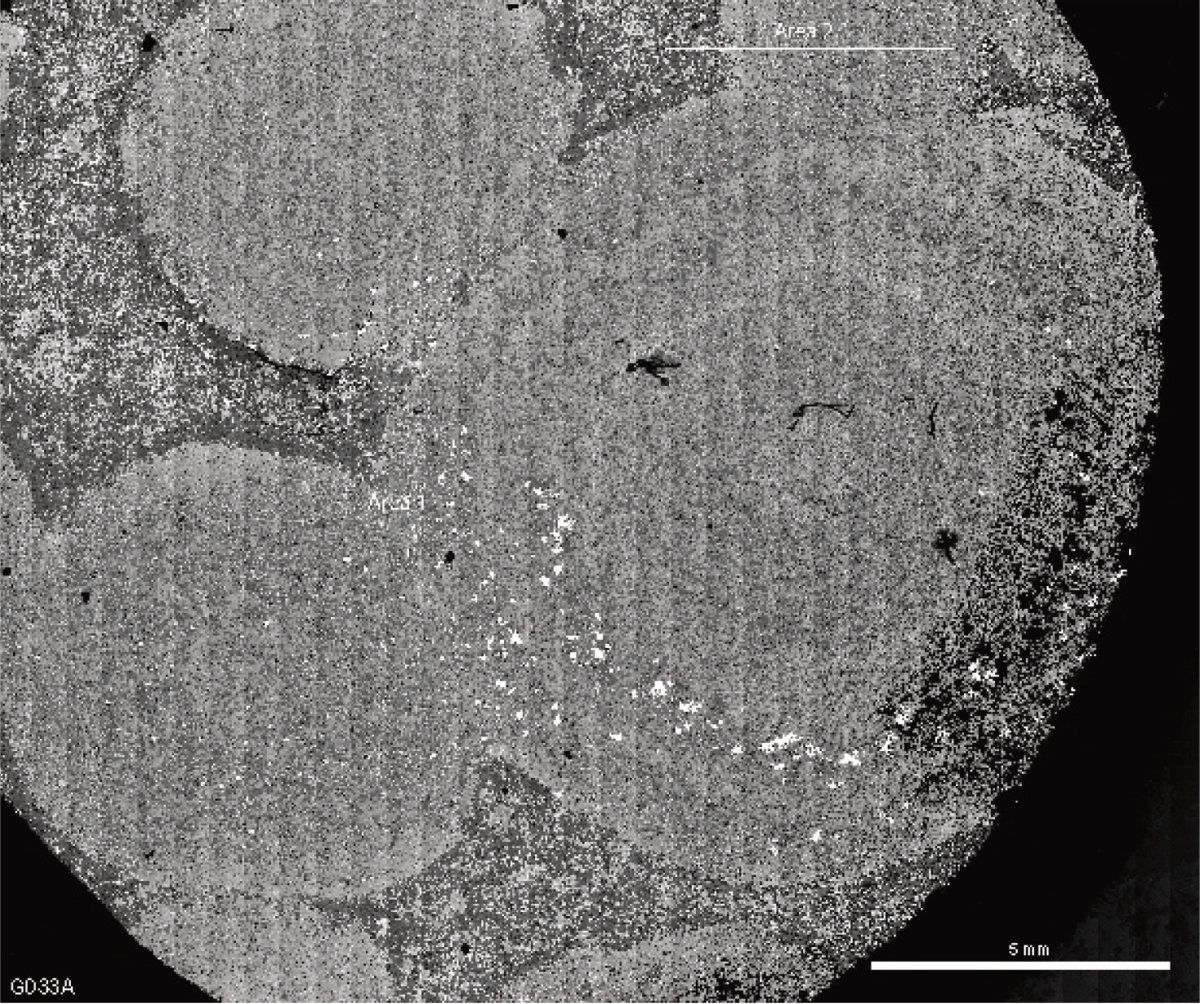

Only the uppermost part of the layer at Gunflint Lake contains true ejecta—the most obvious of which are accretionary lapilli. Notice in Figure 5 that the lapilli contain concentric rings that formed by repeated layering of ash and melt droplets onto the hail-stone like projectiles. In some of the locations near Gunflint Lake, the lapilli are intermixed with large iron-formation fragments (Fig. 6), suggesting that the material was reworked by tsunamis.

The impact layer extends discontinuously from Thunder Bay, Ontario(3), southward into parts of Michigan(4)(5), and westward into Minnesota (see Fig. 2). Although it’s a thin layer—only about 25 feet thick in Minnesota—it’s a very important and remarkable one. Its importance lies in the record of global catastrophe that occurred in a “moment” of the planet’s long geologic history and it is remarkable that such a thin layer has survived weathering and erosion for nearly 2 billion years.

Sudbury impact event

Of the 174 scientifically verified impact structures on Earth, only one is larger, and few are older, than the Sudbury Impact(1). For comparison, the Chicxulub Impact on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, is much younger (~65 million years old) and its crater size is smaller. Yet, the Chicxulub event caused world-wide extinction of many species, including dinosaurs. Clearly, the larger Sudbury impact event would also have had global ramifications. Table 1 shows the effects that might be expected near Gunflint Lake, based on experimental evidence and observations from smaller impacts on Earth and other planets(6).

| Arrival Time | Effect | Modern Analog |

|---|---|---|

| 1. ~13 seconds | Fireball | 3rd degree burns, trees ignite |

| 2. ~2-3 minutes | Earthquakes | Richter scale 10.2 at Sudbury, buildings collapse at Gunflint Lake |

| 3. ~5-10 minutes | Airborne ejecta arrives | A layer 1-3 meters thick, with fragments <1 cm in size |

| 4. ~40 minutes | Air blast | Maximum wind speeds ~1,400 mph |

| 5. ~1-2 hours | Tsunami | None of this magnitude |

The internal organization of units within the impact layer at Gunflint Lake is consistent with the sequence of events outlined on the table. Seismic shaking from earthquakes deformed and fragmented the underlying iron-formation, and caused submarine debris flows that redistributed the fragments into a thick breccia unit. This was followed by deposition of airborne ejecta that rained down on the ocean surface and settled to the sea floor, forming the lapilli unit. Finally, localized reworking of the ejecta and breccia units by tsunamis produced the uppermost unit of mixed fragments and lapilli.

Given the preceeding “context for interpretation,” it is an interesting footnote that the entire layer of breccia and ejecta very likely represents the catastrophic events of a single day; caught during the 48 million years that separate the deposition of Gunflint Iron Formation below from Rove Formation above (Fig. 7).

Despite the fact that large meteorite impacts are exceedingly rare and unlikely in our lifetime, recent geological research demonstrates that the impact process is fundamental to the formation of terrestrial planets. The on-going study of these ancient deposits in the Lake Superior region (Fig. 8) will enhance our understanding of the environmental consequences of impact during the oldest time period in Earth history.

Photo courtesy of McSwiggen and Associates, PA