Minnesota Starwatch

Minnesota Starwatch by Deane Morrison, designed to inform the broadest possible community of the appearance of the nightly sky and current activities in newspapers, continues to be published in several newspapers throughout the state.

Contact:

Deane Morrison

University Relations

(612) 624-2346

morri029@umn.edu

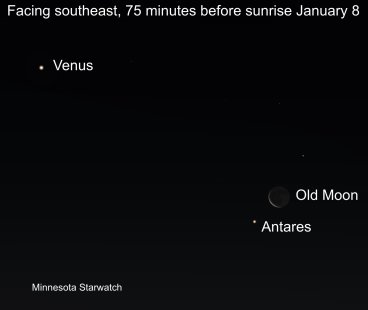

JANUARY 2024

January may be frigid, but the cold air means clearer skies for viewing the jewels scattered among the iconic winter stars. By the 7th, hourglass-shaped Orion, the hunter, and all its companion constellations will be up in the southeast at 8 p.m. The last of the bright winter stars to clear the southeastern horizon is Sirius, in Canis Major, the big dog. Sirius outshines the other stars, but high in the south, brilliant Jupiter dominates the sky. As you gaze at Orion, notice the glowing nebula in his sword. The sword hangs from the three closely spaced stars of his belt, which form the ”waist” of his hourglass shape. Extending a line through the belt stars upward, you’ll see Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus, the bull. The V-shaped face of the bull, formed by stars of the Hyades cluster, is also an eye pleaser. Then look to the upper right of Aldebaran to view the young—astronomically speaking—and beautiful Pleiades star cluster. But as the winter stars climb in the east, Saturn sinks in the west. If you’re unsure which object is the ringed planet, a young crescent moon hangs below it at nightfall on the 13th. In the predawn sky, regal Venus still shines low in the southeast. During the first two weeks of January, watch red Antares, the heart of Scorpius, climb past the planet. On the 8th, don’t miss the spectacle of an old crescent moon threatening to blot out Antares. On the 2nd, Earth reaches perihelion, its closest approach to the sun in an orbit. At that moment we’ll be about 91.4 million miles from our parent star and moving at top speed around it. January’s full moon rises on the 25th and follows the gaggle of winter constellations across the night sky. Following those stars every night is Regulus, the heart of the spring constellation Leo, the lion.

DECEMBER 2023

The dark skies of December form a fitting backdrop for the interplay of the moon and planets and the arrival of the iconic winter stars. In the first half of the month, no moon will interfere with views of the early evening sky. In the west, Saturn drops as Earth leaves it behind in the orbital race, but it will always be up at nightfall. So will Jupiter, a beacon in the eastern sky. East of Jupiter, two famous star clusters herald winter’s approach. About midway between Jupiter and Capella—the bright star in the northeast—you’ll see the Pleiades cluster. The Pleiades are only about 100 million years old, compared to some 4.5 billion years for our sun. The cluster’s thousand-plus stars formed in the same stellar nursery and are approximately 445 light-years away. Below the Pleiades is the V-shaped Hyades cluster, which forms the face of Taurus, the bull. A mere 150 light-years away, it’s the closest star cluster to Earth. The bull’s eye is the bright star Aldebaran, which is closer than the Hyades and not part of the cluster. December’s full moon rises about 45 minutes before sunset on the 26th. It travels the night sky amid the large knot of bright winter constellations, near the left leg of the Gemini twin Castor. In the morning sky, on the 1st brilliant Venus appears in the southeast close to Spica, the brightest star in Virgo, the maiden. But the two quickly separate as Venus sinks and Spica soars. A waning moon visits Spica on the 8th and Venus the 9th. The bright star to the upper left of the pair is Arcturus, in Bootes, the herdsman. Winter begins with the solstice, at 9:27 p.m. on the 21st. At that moment, the sun reaches a point over the Tropic of Capricorn and begins its long journey back north.

NOVEMBER 2023

In November the bright winter constellations begin their grand entry into the evening sky. Leading the parade is Jupiter, the brilliant orb low in the east at nightfall. Of the brightest stars in the array, the first to appear is Capella, in Auriga, the charioteer, which will be low in the northeast. Look above and slightly to the right of Capella for Perseus, a scraggly constellation most easily seen in the cold months. Its brightest star is Mirfak (or Algenib), but it is Algol, the second brightest, that holds a special place in the history of astronomy. Ancient Arab astronomers watched in fascination as Algol went through a cycle of brightening and dimming every 2.87 days. This eerie behavior happens because Algol, a multiple-star system, contains two closely bound stars orbiting each other. As seen from Earth, the dimmer star regularly passes in front of its brighter companion, causing a dip in its brightness. Some ancients identified Algol with a winking eye of Medusa, the Gorgon monster slain by the Greek hero Perseus, who holds her severed head. Also in the evening sky, Saturn appears low in the south at nightfall. Below Saturn is Fomalhaut, dubbed “the loneliest star” because it’s the only bright one in its patch of sky. Fomalhaut's constellation—Piscis Austrinus, the southern fish—is one of the dimmest of all. In the morning sky, we’re treated to a breathtaking spread about an hour and a half before sunrise on the 9th. From east to west, you’ll see Venus and a crescent moon in a tight pair; the panoply of winter constellations; and Jupiter getting ready to set. Also, November’s full moon arrives at 3:16 a.m. on the 27th. The Leonid meteor shower peaks in the predawn sky on the night of the 17th to 18th. Leonids can be quite bright and often leave persistent trails. This year, no moon will interfere.

OCTOBER 2023

August serves up a smorgasbord of celestial delights, starting with a full “super” moon on August 1. As

it rises that evening, the moon will look bigger and brighter than usual, thanks to being less than a day from perigee, its closest approach to Earth in a lunar cycle. Saturn begins August very low in the east at nightfall. All month long it climbs higher as it drifts westward. On the 27th it reaches opposition, when Earth laps it in the orbital race and it appears opposite the sun in the sky. Mid-month will be a great time to view the ringed planet, with a small telescope if possible, because no moon will interfere. In the last few days of August, you may c

atch Jupiter rising in the east in the late evening. Don’t confuse it with Capella, the bright star low in the northeast on those nights. Also at month’s end, Venus rockets into the

eastern predawn sky. Our sister planet joins Sirius—the night sky’s brightest star—and all the iconic winter constellations.The night of August 30, we’re treated to a second super moon. It rises less than an hour before reaching perfect fullness and on the same day as perigee. As the second full moon in a calendar month, it will be dubbed a blue moon. The renowned Perseid meteor shower is expected to peak the night of August 12 to 13. This should be a good year for the shower because we’ll have five hours of moonless sky, starting around 10 p.m. August 12. The Perseids represent the fiery demise of dust particles left by Comet Swift-Tuttle, which last whipped around the sun in 1992 and won’t return until 2125. According to NASA, the nucleus of Swift-Tuttle is about 16 miles across, or about

twice the size of the rock believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs.

SEPTEMBER 2023

In September the fall constellations move to front and center in the south. They include Aquarius and Pisces, which are famous but dim. On the bright side, this year Jupiter joins Saturn in the evening sky. Jupiter rises in the east-northeast by 11 p.m. On the 1st, if you want to identify these two planets, a fat waning moon helpfully positions itself midway between Jupiter, to its lower left, and Saturn, to its upper right. On the 26th, a waxing moon hangs below Saturn. Grab a star chart and look for faint, scraggly Aquarius, Saturn’s current constellation of residence. Also find the Great Square of Pegasus and the Circlet of Pisces, a rather dim ring of stars below and slightly west of the Great Square. And don’t forget the Summer Triangle. September is the best time to see these three bright stars, because they now appear high in the south at nightfall. If you have no binoculars, it still should be easy to find the Northern Cross stretching southwestward from Deneb, the star at the Triangle’s northeast corner. In the predawn sky, Venus appears below the Gemini twins— Castor and Pollux—and Procyon, in Canis Minor, the little dog. A waning moon hangs near Pollux on the 10th, and closer to Venus the next two mornings. Note how Venus, the brightest planet, compares to Sirius, the brightest star. Sirius shines to the right of Venus, and at nearly the same altitude, all month. The evening of the 28th, the third super moon in a row rises, becoming full at 4:57 a.m. the next morning. As the second full moon in a calendar month, it’s also a blue moon. Fall arrives with the autumnal equinox at 1:50 a.m. on the 23rd. At that moment the southbound sun officially crosses the equator, and Earth will be lighted from pole to pole.

AUGUST 2023

August serves up a smorgasbord of celestial delights, starting with a full “super” moon on August 1. As

it rises that evening, the moon will look bigger and brighter than usual, thanks to being less than a day from perigee, its closest approach to Earth in a lunar cycle. Saturn begins August very low in the east at nightfall. All month long it climbs higher as it drifts westward. On the 27th it reaches opposition, when Earth laps it in the orbital race and it appears opposite the sun in the sky. Mid-month will be a great time to view the ringed planet, with a small telescope if possible, because no moon will interfere. In the last few days of August, you may c

atch Jupiter rising in the east in the late evening. Don’t confuse it with Capella, the bright star low in the northeast on those nights. Also at month’s end, Venus rockets into the

eastern predawn sky. Our sister planet joins Sirius—the night sky’s brightest star—and all the iconic winter constellations.The night of August 30, we’re treated to a second super moon. It rises less than an hour before reaching perfect fullness and on the same day as perigee. As the second full moon in a calendar month, it will be dubbed a blue moon. The renowned Perseid meteor shower is expected to peak the night of August 12 to 13. This should be a good year for the shower because we’ll have five hours of moonless sky, starting around 10 p.m. August 12. The Perseids represent the fiery demise of dust particles left by Comet Swift-Tuttle, which last whipped around the sun in 1992 and won’t return until 2125. According to NASA, the nucleus of Swift-Tuttle is about 16 miles across, or about

twice the size of the rock believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs.

JULY 2023

In July Venus ends its long run as an evening star by plummeting into the sunset, a spectacular fall that begins its next trip between Earth and the sun. But it won’t be gone for long. Our brilliant sister planet will reappear in the morning sky in the last days of August. At nightfall the Summer Triangle of bright stars rides high in the east to southeast. Its brightest star is Vega, in Lyra, the lyre. The lyre, often associated with the mythical Greek musician Orpheus, is represented by a parallelogram of stars below Vega. The next brightest Triangle star is Altair, in Aquila, the eagle. The third Triangle star—Deneb—forms the tail of Cygnus, the swan, and the “head” of the Northern Cross. Grab your binoculars and explore these stars and the whole Triangle area. In the predawn sky, Saturn and Jupiter appear low in the southeast and east, respectively, on July 1. As the month goes by, both planets drift higher and westward. Low in the northeast is the brilliant star Capella, in Auriga, the charioteer. The evening of the 2nd, a super moon—a full moon that’s near the closest point to Earth in a lunar orbit—rises in the aptly named Teapot of Sagittarius. That night the moon follows a low trajectory across the night sky and sets in the west half an hour before sunrise on the 3rd, shortly before reaching perfect fullness. The waning moon visits Saturn on the 7th and Jupiter on the 11th and 12th. On the 14th and 15th, an old moon makes a pretty sight with Jupiter, Capella, and the Pleiades star cluster. The star below the Pleiades will be Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus, the bull. On July 6 Earth reaches aphelion, the farthest point from the sun in its orbit. At that moment our planet will be 94.5 million miles from its parent star.

The University of Minnesota offers public viewings of the night sky at its Duluth and Twin Cities campuses. For more information, see:

Duluth, Marshall W. Alworth Planetarium: www.d.umn.edu/planet

Twin Cities, Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics: www.astro.umn.edu/outreach/pubnight

Check out astronomy programs, free telescope events, and planetarium shows at the University of Minnesota's Bell Museum:

www.bellmuseum.umn.edu/astronomy

Find U of M astronomers and links to the world of astronomy at http://www.astro.umn.edu

6/22/23 Contact: Deane Morrison, University Relations, (612) 721-6003, morri029@umn.edu.

JUNE 2023

As June opens, Venus forms a line with the Gemini twins. Nearby, Mars is poised to drift through the subdued but lovely Beehive star cluster in Cancer, the crab. At nightfall June 1 and 2, look for brilliant Venus above the western horizon. To the right of Venus, Pollux—the brighter Gemini twin—and Castor complete an almost perfectly straight line. Above and left of Venus, Mars still ornaments the evening sky. On June 1, 2, and 3, grab your binoculars and watch Mars sail through the Beehive cluster. The Beehive is also known as Praesepe, Latin for “manger.” As Mars leaves the Beehive, it passes between two somewhat bright stars that frame the manger. These are the northern and southern asses—Asellus Borealis and Asellus Australis, respectively—which feed at the manger. Looking upward and leftward again, the bright spring star Regulus, the heart of Leo, the lion, is closing in on the two planets. Watch this space between Tuesday and Friday, the 20th and 23rd, as a young waxing moon sweeps past Venus, Mars, and finally Regulus. June’s full moon rises big and round the evening of the 3rd. It crosses the night sky next to Antares, the gigantic red heart of the summer constellation Scorpius. In the predawn sky, Saturn is well up in the southeast and Jupiter spends the month climbing up from the eastern horizon. If you’re out early enough on the 14th, don’t miss the pretty pairing of a waning crescent moon and Jupiter. Summer arrives with the solstice at 9:58 a.m. on the 21st, when the sun reaches a point over the Tropic of Cancer. At that moment an observer in space would see sunlight stretching from the Antarctic Circle up to the North Pole and over to the Arctic Circle on the dark side of the planet.

The University of Minnesota offers public viewings of the night sky at its Duluth and Twin Cities campuses. For more information, see:

Duluth, Marshall W. Alworth Planetarium: www.d.umn.edu/planet

Twin Cities, Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics: www.astro.umn.edu/outreach/pubnight

Check out astronomy programs, free telescope events, and planetarium shows at the University of Minnesota's Bell Museum:

www.bellmuseum.umn.edu/astronomy

Find U of M astronomers and links to the world of astronomy at http://www.astro.umn.edu

5/18/23 Contact: Deane Morrison, University Relations, 612) 721-6003, morri029@umn.edu.

MAY 2023

During May, brilliant Venus holds its own above the western horizon as the last of the bright winter stars stream past it.

Our sister planet begins the month by gliding between Betelgeuse, in Orion, and Capella, in Auriga, the charioteer. Betelgeuse, to the lower left of Venus, is outshone by both the planet and high, brilliant Capella. As those stars drop away, Venus passes through Gemini, all the while following a course toward Mars, which appears to be fleeing its approach.

Mars starts the month below Pollux, the brighter of the Gemini twins. As Gemini sinks, Pollux glides past the red planet.

The assemblage is enhanced between Monday and Wednesday, the 22nd and 24th, when a waxing moon joins the stars and planets. The bright star passing to the lower left of Venus those nights is Procyon, in Canis Minor, the little dog. The moon appears next to Pollux on the 23rd and above Mars on the 24th.

The moon begins the month below the triangular hindquarters of Leo, the lion. Leo’s head—the backward question mark of stars known as the Sickle—now dips a bit as the constellation begins its inevitable descent into the sunset. On the 3rd, the moon shines just above Spica, the only bright star in Virgo, the maiden. Above them, radiant Arcturus anchors the kite-shaped constellation Bootes, the herdsman.

May’s full moon arrives at 12:34 p.m. on Friday, the 5th. The moon sets in the west shortly before sunrise that day, so your best bet may be to enjoy the moonrise on the evening of the 4th or 5th. Also in the predawn hour, a waning moon visits Saturn in the southeastern sky on Saturday, the 13th. On Wednesday, the 17th, a thin lunar crescent visits Jupiter very low in the east, in the midst of the sun’s foreglow.

The University of Minnesota offers public viewings of the night sky at its Duluth and Twin Cities campuses. For more information, see:

Duluth, Marshall W. Alworth Planetarium: www.d.umn.edu/planet

Twin Cities, Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics: www.astro.umn.edu/outreach/pubnight

Check out astronomy programs, free telescope events, and planetarium shows at the University of Minnesota's Bell Museum:

www.bellmuseum.umn.edu/astronomy

Find U of M astronomers and links to the world of astronomy at http://www.astro.umn.edu

4/22/23 Contact: Deane Morrison, University Relations, 612) 721-6003, morri029@umn.edu.

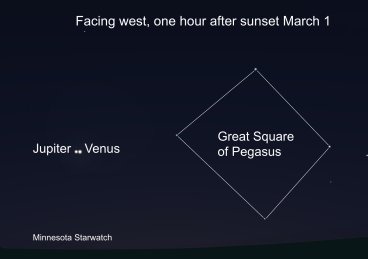

MARCH 2023

March always brings passages—winter to spring, ice to slush, sun to the Northern Hemisphere. This year, the month begins with an uncommon passage as the two brightest planets sweep by each other above the southwest horizon.

On Wednesday, the 1st, Jupiter passes within a moon width of brilliant Venus. The gap between them quickly widens as Jupiter falls into the sun’s afterglow. On Wednesday, the 22nd, a thin crescent moon appears above Jupiter about 40 minutes after sunset. The next night, the moon hangs below Venus.

East of the planetary pair, Mars rides high at nightfall as the bright winter stars stream past it. In mid-month Mars glides between Betelgeuse, the giant red star at Orion’s right shoulder, and brilliant Capella, in Auriga, the charioteer. At month’s end the red planet will be heading into Gemini. Enjoy this feast of stars and Mars now, before the winter constellations also slip into the sunset.

March’s full moon arrives at 6:40 a.m. on Tuesday, the 7th, after crossing the night sky below the spring constellation Leo, the lion. The moon sets in the west shortly after reaching fullness, so plan accordingly.

Spring begins with the vernal equinox at 4:24 p.m. Monday, the 20th. At that moment the sun crosses the equator heading north, and Earth will be lighted from pole to pole. From then until the September equinox, the day length increases as we travel north. Also, the day length increases most rapidly near the spring equinox because the sun is then moving most rapidly northward.

If you’re out at the end of evening twilight between the 10th and the 22nd, look for a faint, broad cone of light extending up from the western horizon along the sun’s path. This is the elusive zodiacal light, the result of sunlight reflecting off dust in the plane of the solar system. Recent evidence has suggested a Martian origin for the dust.

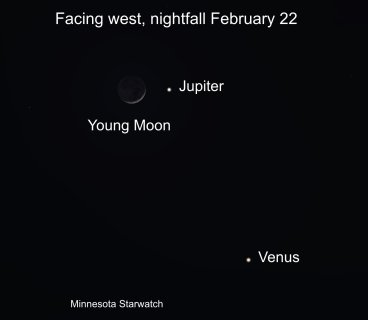

FEBRUARY 2023

In February Venus climbs above the sunset horizon and settles into its latest reign as an “evening star.” But the sun is also climbing, so we have to go out later each night to see our sister planet against a dark sky.

As Venus surges, Jupiter drops toward it, thanks to Earth leaving the giant planet behind in the orbital race. Look for Jupiter in the southwest and watch the two brightest planets draw closer each night. The pair ends the month poised to pass each other on March 1.

While Earth regularly leaves Jupiter in the dust, it can’t do that to Venus because it’s closer to the sun and speedier than Earth. Thus, Venus climbs and falls due to its own movement. When it’s an evening star it’s chasing us, but when it appears in the morning sky we’re “eating its dust.”

Mars is now high in the south at nightfall. The red planet is fading but still easy to find; look east of the Pleiades star cluster and above Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus, the bull. Also, take this chance to compare Venus, the brightest planet, to Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Sirius is the lowest of the bright winter stars now assembled in the southeast and shines to the lower left of Orion’s hourglass figure. Try in mid-month, when Venus will be higher at nightfall and no moon will interfere.

February’s full moon arrives on the 5th. During the moon’s next cycle it visits Jupiter and Venus on the 21st and 22nd and Mars on the 27th.

On Groundhog Day we celebrate an ancient astronomically based Celtic holiday called Imbolc, or lamb’s milk. It marked the start of the lambing season and was one of four cross-quarter days falling midway between a solstice and an equinox. How the groundhog became linked to this day isn’t clear. As for why seeing its shadow, or not, was important, one theory suggests that if the day was cloudy and shadowless, it portended rain and softening farm fields. But a clear and cold day signaled a more stubborn winter.

JANUARY 2023

The new year opens with Venus climbing out of the sun’s afterglow. On Sunday, January 22, Saturn drops past Venus as Earth’s orbital motion sends the ringed planet tumbling into the sunset. Look for the pair of planets very low in the southwest just as the sky darkens.

If you catch Venus and Saturn, also turn your eyes to Jupiter, the beacon high in the southwest, and high-flying, reddish Mars, the second-brightest object in the knot of winter constellations in the east. With the right timing, you can simultaneously view Venus—the brightest planet—and Sirius, the brightest star (after the sun) and the last of the iconic winter stars to clear the eastern horizon.

January’s full moon arrives on Friday, the 6th. It rises before sunset and becomes full at 5:08 p.m. After nightfall it shines to the right of the Gemini twins Pollux (the brighter) and Castor. Between about 9 p.m. and midnight on Friday the 30th, you’ll have plenty of time to watch a waxing moon of the next cycle glide close below Mars.

In the predawn sky, the Northern Cross lies on its side below brilliant Vega, the jewel of Lyra, the lyre. On the 18th, a thin waning moon rises close to Antares, the heart of Scorpius.

Earth reaches perihelion, the closest point to the sun in its orbit, at 10:17 a.m. on the 4th, when our planet reaches its top speed. Changes in Earth’s speed go largely unnoticed, but they show up in the length of the seasons. Because Earth goes so fast in the middle of its journey from the September to the March equinox, the combined fall-winter season is about seven days shorter for us than for our friends in the Southern Hemisphere.