New method of pancreatic islet cryopreservation is major breakthrough for diabetes cure

April 29, 2022 — Engineering and medical researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities and Mayo Clinic have developed a new process for successfully storing specialized pancreatic islet cells at very low temperatures and rewarming them, enabling the potential for on-demand islet transplantation. The breakthrough discovery in cryopreservation is a major step forward in a cure for diabetes.

In new research published in Nature Medicine, University of Minnesota researchers have developed a new method of islet cryopreservation that solves current storage challenges by enabling quality-controlled, long-term preservation of the islet cells that can be pooled and used for transplant.

The study was led by John Bischof, PhD — a Distinguished McKnight University Professor, a faculty member in the Departments of Mechanical Engineering and Biomedical Engineering, and director of the University’s Institute for Engineering in Medicine — and Erik Finger, MD, PhD, associate professor of surgery in the University of Minnesota Medical School, M Health Fairview. Both Bischof and Finger are a part of the National Science Foundation Engineering Research Center for Advanced Technologies for the Preservation of Biological Systems (ATP-Bio) and co-direct the Center for Organ Preservation at the University of Minnesota.

The study found:

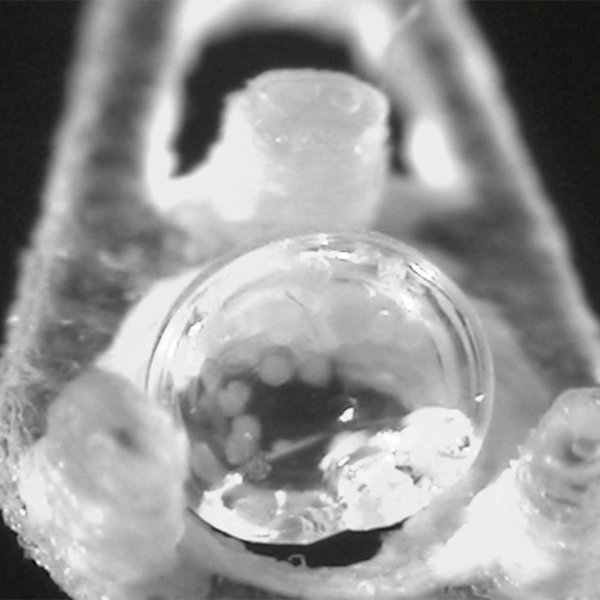

- By using a specialized cryomesh system, excess cryoprotective fluid was removed, which allowed rapid cooling and rewarming on the order of tens of thousands of degrees per second while avoiding problematic ice formation and minimizing toxicity.

- This new cryopreservation method demonstrated high cell survival rates and functionality (90% for mouse islet cells and about 87% for pig and human islet cells), even after nine months of storage. Storage with this potential cryopreservation approach is theoretically indefinite.

- In mice, the transplantation of these cryopreserved islet cells cured diabetes in 92% of recipients within 24 to 48 hours after transplant.

- These results suggest that this new cryopreservation protocol may be a powerful means of improving the islet supply chain, allowing pooling of islets from multiple pancreases and thereby improving transplantation outcomes that can cure diabetes.

“Our work provides the first islet cryopreservation protocol that simultaneously achieves high viability and function in a clinically scalable protocol,” Bischof said. “This method could revolutionize the supply chain for islet isolation, allocation, and storage before transplant. Through pooling cryopreserved islets prior to transplant from multiple pancreases, the method will not only cure more patients, but also make better use of the precious gift of donor pancreases.”

The researchers also pointed out that this method has the ability to be scaled up to reach large numbers of people worldwide who suffer from this progressively debilitating disease.

“This exciting development by our multidisciplinary research team brings engineering approaches to solve an important medical challenge—the cure of diabetes,” said Finger. “Despite decades of research, islet transplantation has remained ‘just around the corner;’ ever with great promise, but never quite within reach. Our technique for cryopreserving islets for transplantation could be a significant step towards finally achieving that lofty goal.”

In addition to Bischof and Finger, the research team included, from the University of Minnesota, co-first author postdoctoral fellows Li Zhan (mechanical engineering) and Joseph Sushil Rao (surgery). Also part of the study team were Nikhil Sethia (chemical engineering and materials science), Zonghu Han (mechanical engineering), Diane Tobolt (surgery), Michael Etheridge (mechanical engineering), and Cari S. Dutcher (mechanical engineering; chemical engineering and materials science). Mayo Clinic researchers who were part of the team included Michael Q. Slama and Quinn P. Peterson.

This work was supported by grants from Regenerative Medicine Minnesota, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding was provided by the University of Minnesota’s Schulze Diabetes Institute, the Division of Transplantation at the Department of Surgery, Kuhrmeyer Chair in Mechanical Engineering, and the Bakken Chair in the Institute for Engineering in Medicine. The researchers also acknowledge the J.W. Kieckhefer Foundation, the Stephen and Barbara Slaggie Family, and the Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan Foundation for supporting this work. The University of Minnesota’s Characterization Facility was used in this research.

–

Adapted from a UMN College of Science & Engineering news release