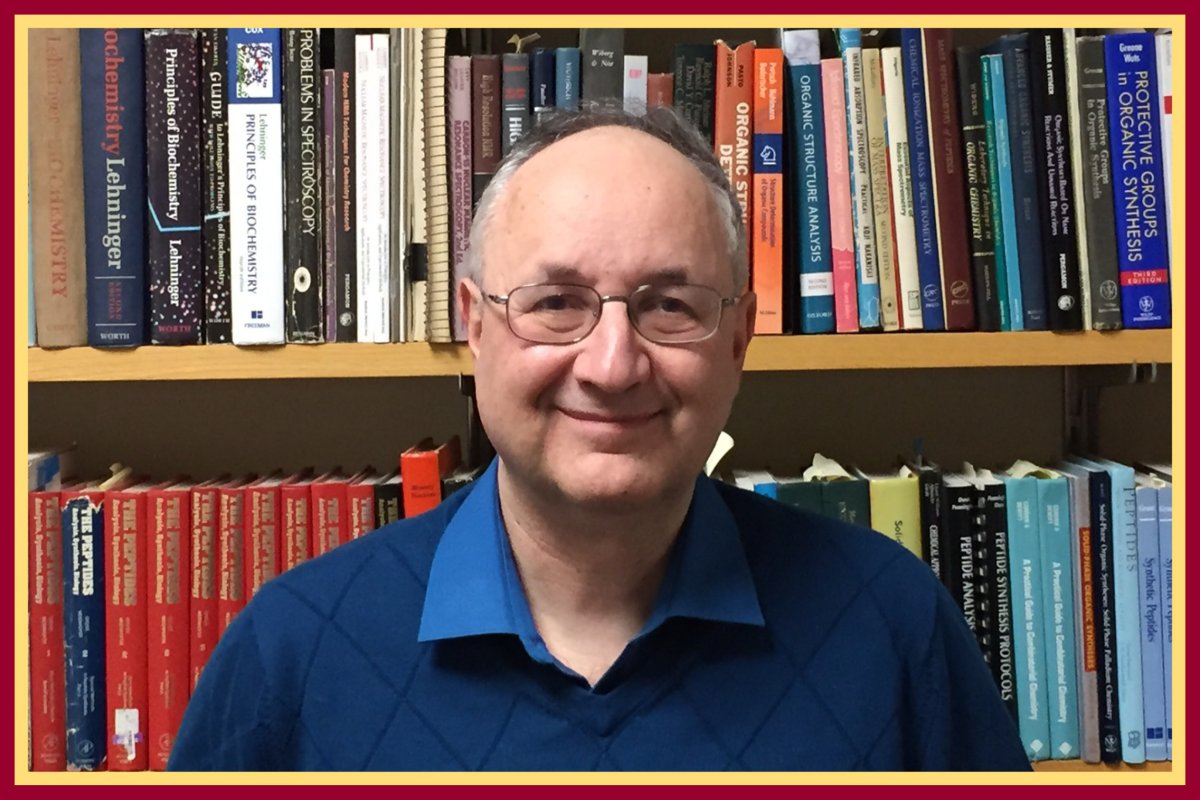

Professor George Barany retires after a 44 year career at the University of Minnesota

MINNEAPOLIS / ST. PAUL (6/6/2024) Distinguished McKnight University Professor George Barany retired from the University of Minnesota on May 26th, 2024, after a 44 year career in the Department of Chemistry. Barany, who was most recently honored with election to the National Academy of Inventors in 2020, is renowned for his long-standing leadership and pioneering innovations in the field of peptide synthesis methodology, for his role in the invention of revolutionary universal Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) arrays for detection of genetic diseases, and for numerous discoveries in the field of organosulfur chemistry, including synthesis of the active ingredient of garlic.

It runs in the family

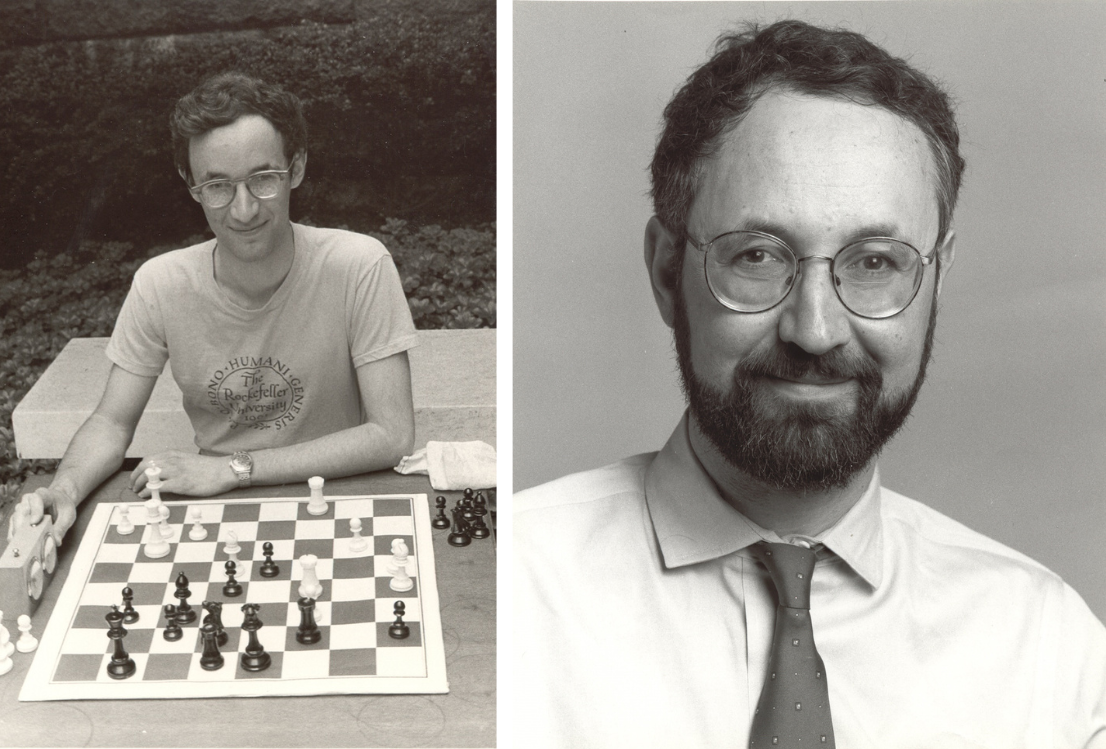

George Barany grew up in New York City, often hanging out in his parents’ research laboratories when he wasn’t pursuing his regular school work, sports like tennis, or games like chess. Both his mother, Kate Bárány, and father, Michael Bárány, were Holocaust survivors who came to the United States with their two small sons in 1960. Kate went on to build an illustrious career studying the physiology of muscle and muscle disease, and was also a trailblazer on a variety of women’s issues. Michael is best known for establishing the relationship between the speed of muscle contraction and the adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) activity of the muscle protein myosin, and was one of the first scientists to study live tissue using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The Kate and Michael Bárány Conference Room (117/119 Smith Hall) was dedicated in their honor in 2012.

“I guess before anything else, I was a math whiz,” George says as he reminisces about his childhood. Over holiday and summer breaks George carried out science fair projects in his father’s biochemistry lab. George was so advanced in mathematics and the sciences that he skipped undergraduate studies altogether, and went straight on to graduate school from the prestigious Stuyvesant High School at the age of 16.

At The Rockefeller University, George worked with Professor R.B. Merrifield, where he pursued his interests in experimental peptide and protein biochemistry. He published his first paper in 1973, on the synthesis of an ATP-binding peptide, a project that had its roots in high school research in his father’s lab and a summer rotation project in Merrifield’s lab. George graduated with his PhD at age 22, but continued to work with Merrifield for three more years before launching his independent career.

“I had a lot of beginner's luck. The first peptide I made was my high school science project, which morphed into my first year project with Merrifield. That peptide then wound up being written up in Lehninger’s now-classic textbook. So, as a teenager, I was learning biochemistry from the first edition of the text, and then by the time the second edition was published, it had my molecule in there!”

Four decades of research at UMN

In 1980, Barany was hired to the University of Minnesota faculty. Over the course of his four decade career, Barany pursued his research interests in peptide synthesis, and developed a myriad of new interests. His research, described in nearly 390 scientific publications, has covered areas ranging from the chemical synthesis of garlic constituents, to studies on the mechanisms of protein folding, to methods for chemical combinatorial libraries, to advances in the preparation of antisense DNA and RNA, and to the development of DNA and PNA arrays for the multiplex detection of genetic diseases. He currently holds 38 issued U.S. patents.

Barany revolutionized peptide chemistry through his concept of orthogonality, leading to the development of widely used toolkits for synthesizing hormones and proteins. His research group was collaboratively involved in the invention and commercialization of useful peptide synthesis resin supports (PEG-PS, CLEAR), anchoring linkages (PAL, HAL, XAL, BAL), and reagents (e.g., Clear-OX, an elegant “chaperone” for the creation of disulfide bridges) that expanded the range of molecular targets accessible for research. In another avenue of his research, Barany collaborated with Professor Karin Musier-Forsyth (then at UMN) and Professor Robert Hammer (then at Louisiana State University) on the invention of sulfurization reagents for DNA and RNA, chemistry that is essential for antisense therapeutics.

Starting in the mid 1990s, Barany collaborated with his brother, Professor Francis Barany, and with Professor Hammer, to develop universal arrays for sensitive and accurate mutational analysis, which became foundational for personalized cancer treatment approaches and genome sequencing advancements. This “Zipcode” technology – broadly used for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection and haplotype mapping – was the basis of comprehensive tumor profiling by the National Institutes of Health Cancer Genome Anatomy Project. Advances built on the foundational research of Barany, Barany, and Hammer make it possible to sequence entire genomes in days rather than years, resulting in improved capability to diagnose diseases more promptly and accurately.

“I never thought I'd make a whole career out of peptides,” Barany said in a recent interview. “I just thought it was something that needed to get done along the way to doing what I really was interested in, which was understanding how proteins work, and maybe even being able to design a protein. But, as it turned out, just the process of making peptides turned out to be much harder than it had appeared to an enthusiastic but naive teenager.”

Over the course of his career, Barany has been recognized numerous times for his excellence in research and teaching. In 1997, he was the first Department of Chemistry faculty member to be named a Distinguished McKnight University Professor. His many honors include a Searle Scholar award (1982), the Vincent du Vigneaud Award for outstanding achievements in peptide research (1994), the Ralph F. Hirschmann Award in Peptide Chemistry from the American Chemical Society (2006), and the Murray Goodman Scientific Excellence & Mentorship Award from the American Peptide Society (2015). For his lifelong commitment to “demonstrating a highly prolific spirit of innovation in creating or facilitating outstanding inventions that have made tangible impacts on the quality of life, economic development, and the welfare of society,” Barany was elected as a Fellow of the National Academy of Inventors in 2020.

Brainteaser aficionado

Outside of the lab, Barany is devoted to his family, and is a lifelong lover of games, puzzles, and sports (both as a participant and as a spectator). Since he began creating crossword puzzles in 1999, Barany has constructed several hundred professional-quality puzzles. His puzzles have been featured in the New York Times, the Chronicle of Higher Education, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Minnesota magazine, and Chemical & Engineering News, to name just a few. Barany’s hobby has connected him to dozens of new friends and collaborators, and he now enjoys mentoring new puzzlers on crossword puzzle creation. For example, in Spring 2024, Barany and Chemistry graduate student Rowan Matney created and shared a Pi Day themed crossword for the Department’s annual Pi(e) Day celebration.

Interested readers can find many of his puzzles at the George Barany and Friends webpage. A new edition of that site is scheduled to launch in the Summer of 2024; please email barany@umn.edu if you would like to receive relevant notifications.

What’s next for Professor Emeritus Barany?

On June 8th, 2024, a symposium entitled A Half Century of Solving Puzzles in Peptide and Sulfur Science will take place in Chicago, Illinois. The event will bring together many of Barany’s closest and most successful colleagues and protégés from as far away as Europe, China, and South Africa, as well as from both US coasts and the midwest. The symposium will feature about a dozen scientific talks on a wide range of topics appealing to George’s eclectic interests – including contributions from his brother and both of his children! Barany says he is looking forward to a weekend filled with engaging discussions and memories to celebrate the closing of this phase of his career. He is also touched by the fact that the International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics will be putting together a special issue in his honor.

In his retirement, Barany says he is looking forward to having more free time for traveling with his wife Barbara – herself a retired chemist and educator – to visit their adult children and young grandchildren. Their son, Michael, lives in Scotland, and their daughter, Deborah, resides in the US state of Georgia. “I figure I've had a great career – I've done a lot of things. Now it's time to spend more time with my grandchildren!” Barany also plans to continue working on crossword puzzle collaborations and hopes to pass a love for wordplay on to his grandkids. A secondary goal is to reread all of the required reading from junior and senior high school, in the hope that it will now make sense through the lens of adult life experience. Finally, through the kindness of several colleagues, Barany has put the administrative and fundraising aspects of academia in the rearview mirror, and resumed lab work – with his own hands – that he hopes will lead to additional high-impact publications.

When he reflects on his time at the University of Minnesota, Barany says his greatest pride comes from the students, at all levels, that he has mentored over the years. “Our lab certainly developed much useful chemistry and had influential insights on a range of scientific topics, but ultimately, it’s all about working with young people and watching them grow into independent and successful scientists and other professionals. It is just amazing, and that is probably my ultimate legacy.”