The Peopling of Minnesota

-Written by Josh Feinberg, IRM Associate Director, Professor

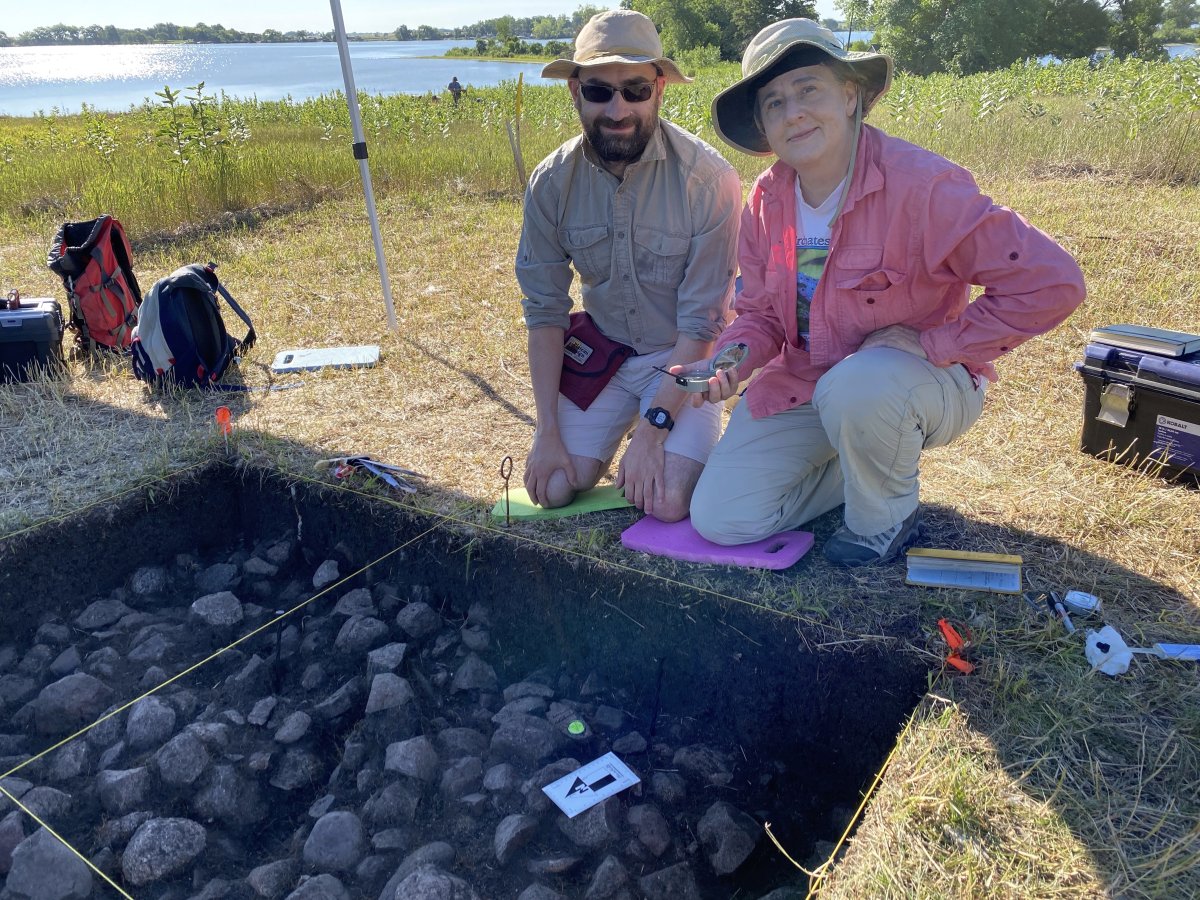

How long have people lived in Minnesota? How did they interact with the landscape? What evidence do we have of this history? These are some of the questions guiding researchers at the Institute for Rock Magnetism (IRM) as they participate in a partnership with the Science Museum of Minnesota (SMM) to study some of the state’s most important archaeological sites. Much of their work focuses on archaeological sites situated on small islands in lakes in the southwestern part of Minnesota that escaped wide-spread disruption associated with intensive farming over the last ~150 years. Some of these sites show evidence of successive waves of human occupation extending back more than 10,000 years in the form of carefully shaped stone arrowheads, discarded remains of food processing (seeds, phytoliths, bones, and shells), and most importantly for IRM researchers: heat-treated materials, including ceramics, fire-cracked rocks, and the remains of campfire hearths. The IRM is contributing to this effort by using the magnetic properties of soils and other materials at these archaeological sites to pinpoint when human occupation began, and by developing a first-of-its-kind Archaeomagnetic Reference Curve for the upper Midwest to date heat-treated materials.

Dating archaeological features within Minnesota has long been a challenging problem. While radiocarbon dating remains the gold standard for determining the age of artifacts and features, the wet and slightly acidic soils of Minnesota often do not preserve material suitable for radiocarbon analyses. In these instances, alternative dating techniques are needed to determine when a site was occupied or when an object was created. Archaeomagnetism is an alternate technique that has been used successfully for decades at archaeological sites in Europe and the Middle East but has not yet been widely employed in the United States and has not been used at all in Minnesota. This technique relies on the observation that the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field waxes and wanes over decadal timescales, and that heat-treated objects record the strength of the geomagnetic field at the instant when they last cooled. We can recover information about the strength of the ancient field using modern instrumentation at the Institute for Rock Magnetism. By collecting such data from ceramic samples whose ages are tightly constrained from radiocarbon measurements, we can establish an Archaeomagnetic Reference Curve that can be used to date other heat-treated materials that are not amenable to radiocarbon dating. The scientific approach for this dating technique is already fully developed in peer-reviewed literature, with origins in the 1950s. In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, it is a standard method used by national heritage agencies. We believe it is a ripe opportunity to expand the range of dating tools available for archaeological materials in Minnesota.

This work is very much a team effort that amplifies the strengths and expertise of its diverse members. It also showcases the incredible scientific resources that we have here in Minnesota. IRM scientists helping to lead the project include Master’s student Declan Ramirez, Associate Research Professor Max Brown, and Professor Josh Feinberg. SMM staff include Dr. Ed Fleming, the Curator of Anthropology, and Mara Taft, a Curatorial Assistant, who lead excavations and document and archive all ceramics, lithics, and faunal remains. Although no human remains have been discovered, site excavations and data interpretations are conducted in close consultation with Tribal Historic Preservation Officers Cheyanne St. John, Samantha Odegard, and Noah White from the Lower and Upper Sioux Indian Communities and the Prairie Island Indian Community, respectively. UMN Anthropology Professor Kat Hayes provides informed perspectives about the methods used to create different styles of ceramics discovered across the site. Charles Umbanhowar Jr. (St. Olaf College) and Mark Edlund (SMM) have collected sediment cores adjacent to some of the island archaeological sites for paleoenvironmental analysis.

While this project is just now gathering speed, we hope that it will be a line of fruitful research for years to come. Departmental friends are encouraged to reach out with their interest!